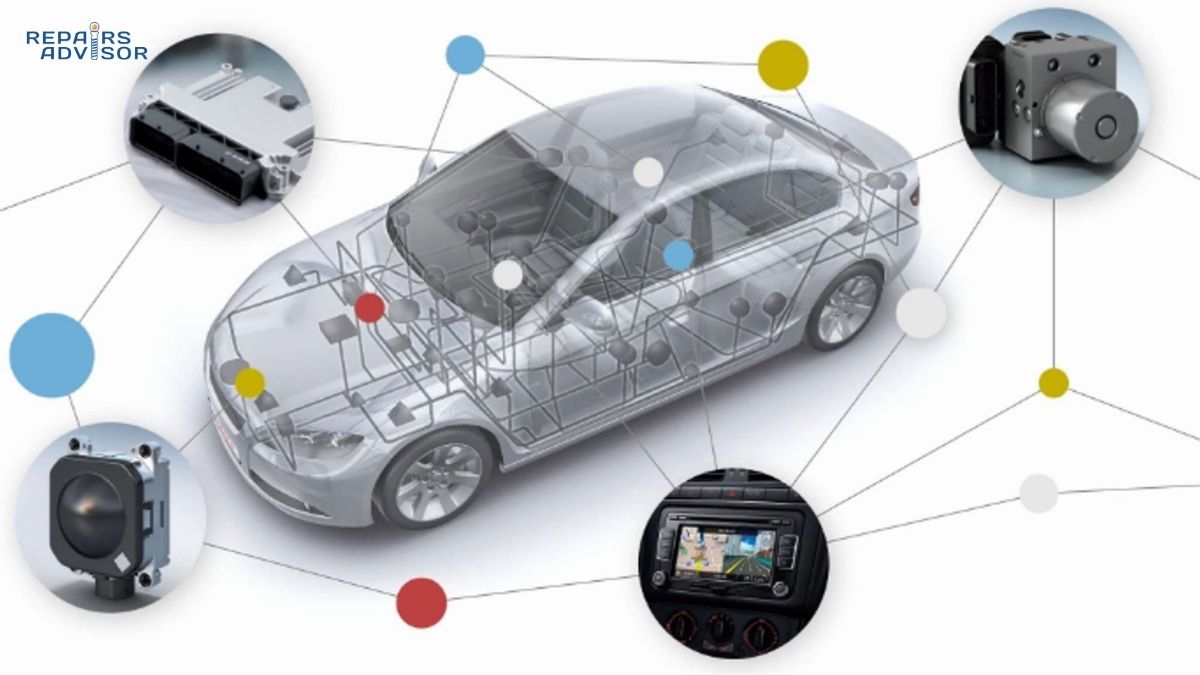

Modern vehicles have evolved far beyond simple mechanical machines into sophisticated mobile computing platforms. Today’s cars contain over a mile of wiring connecting hundreds of sensors, cameras, control units, and displays—all generating and sharing massive amounts of data every second. At the heart of this transformation is Automotive Ethernet, a revolutionary networking technology that’s fundamentally changing how vehicle systems communicate.

Traditional automotive networks like CAN bus were designed in the 1980s when vehicles needed to exchange simple messages between a handful of controllers. These legacy systems top out at 1 megabit per second—adequate for basic engine management and body electronics, but completely inadequate for today’s advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS), 360-degree camera arrays, radar sensors, and autonomous driving features that require gigabits per second of bandwidth.

Automotive Ethernet solves this bandwidth crisis while simultaneously reducing vehicle weight and manufacturing costs. By adapting proven Ethernet technology for the harsh automotive environment, engineers have created networks capable of 100 megabits to 10+ gigabits per second data transfer using lighter, less expensive cabling than traditional harnesses. This scalability makes Automotive Ethernet essential for current ADAS implementations and future autonomous vehicles that will generate terabytes of data daily.

Understanding how Automotive Ethernet works reveals why major manufacturers like BMW, Volkswagen, Tesla, and Ford have already integrated it into their vehicle architectures. This comprehensive guide explores the physical layer technology, network architecture, real-world applications in ADAS systems, integration with legacy networks, and the critical role this technology plays in enabling the connected, autonomous vehicles of tomorrow. Whether you’re an automotive technician, engineer, or enthusiast, you’ll gain deep insight into the networking backbone powering modern vehicle innovation.

For context on traditional vehicle networks, see our guide on how vehicle networks work with CAN bus and communication.

Why Automotive Ethernet Is Critical for Modern Vehicles

The Bandwidth Crisis in Automotive Networks

The automotive industry faces an unprecedented data challenge. Legacy networking protocols that served vehicles well for decades simply cannot support the bandwidth requirements of modern automotive technology. Controller Area Network (CAN bus)—the workhorse of automotive communications since the 1980s—maxes out at 1 megabit per second with data packets limited to just 8 bytes. FlexRAY, introduced for more demanding applications, reaches 10 Mbps with 254-byte packets. Local Interconnect Network (LIN bus), used for basic body electronics, crawls along at 20 kilobits per second. These speeds were perfectly adequate when vehicles needed to exchange simple messages about engine temperature, throttle position, or window switch status.

Today’s vehicles demand exponentially more bandwidth. A single high-definition camera streaming video requires 5 to 25 megabits per second. A complete 360-degree surround view system with four to six cameras needs over 100 Mbps combined. Each radar sensor contributes 10 to 50 Mbps of environmental scanning data. LiDAR systems, essential for autonomous driving, generate point clouds requiring 100+ Mbps of bandwidth. Add high-resolution infotainment displays streaming video at 25+ Mbps, diagnostic data logging at 10+ Mbps, and you quickly exceed what traditional networks can deliver.

The numbers become staggering when you consider fully autonomous vehicles. A single self-driving car can generate over 4 terabytes of data per day from its sensor array. ADAS systems at Level 2 and above require real-time sensor fusion—combining camera, radar, and LiDAR data—at gigabit speeds with microsecond-level timing precision. Over-the-air software updates, now standard for electric vehicles and advanced models, need high-speed, reliable data transfer to update complex systems without requiring dealer visits. Traditional automotive networks simply cannot scale to meet these demands.

Automotive Ethernet provides the solution. With base speeds starting at 100 Mbps and scaling to 10 gigabits per second or higher, it delivers the bandwidth modern vehicles require. Unlike CAN bus where all nodes share the same bandwidth and must arbitrate for bus access, Automotive Ethernet uses a switched architecture where each connection maintains its full rated speed. This means a vehicle can simultaneously stream multiple HD cameras, process radar and LiDAR data, handle diagnostic communications, and serve high-resolution infotainment displays—all without bandwidth bottlenecks.

Learn more about how these systems integrate in our articles on adaptive cruise control with radar and camera integration and sensor fusion for ADAS.

Weight and Cost Reduction

Beyond bandwidth, Automotive Ethernet delivers substantial physical benefits that directly impact manufacturing costs and vehicle performance. The traditional approach to automotive wiring creates significant challenges. The average car contains over a mile of wiring when you account for all the harnesses connecting various systems. This wiring harness ranks as the third heaviest component in a typical vehicle, adding considerable mass that hurts fuel economy in conventional vehicles and reduces range in electric vehicles. The complexity extends to manufacturing—wiring harness installation represents approximately 50% of labor costs during automobile assembly. Multiple network protocols (CAN, LIN, FlexRAY, MOST for multimedia) each require different cable types, connectors, and routing considerations, creating a tangled mess of harnesses throughout the vehicle.

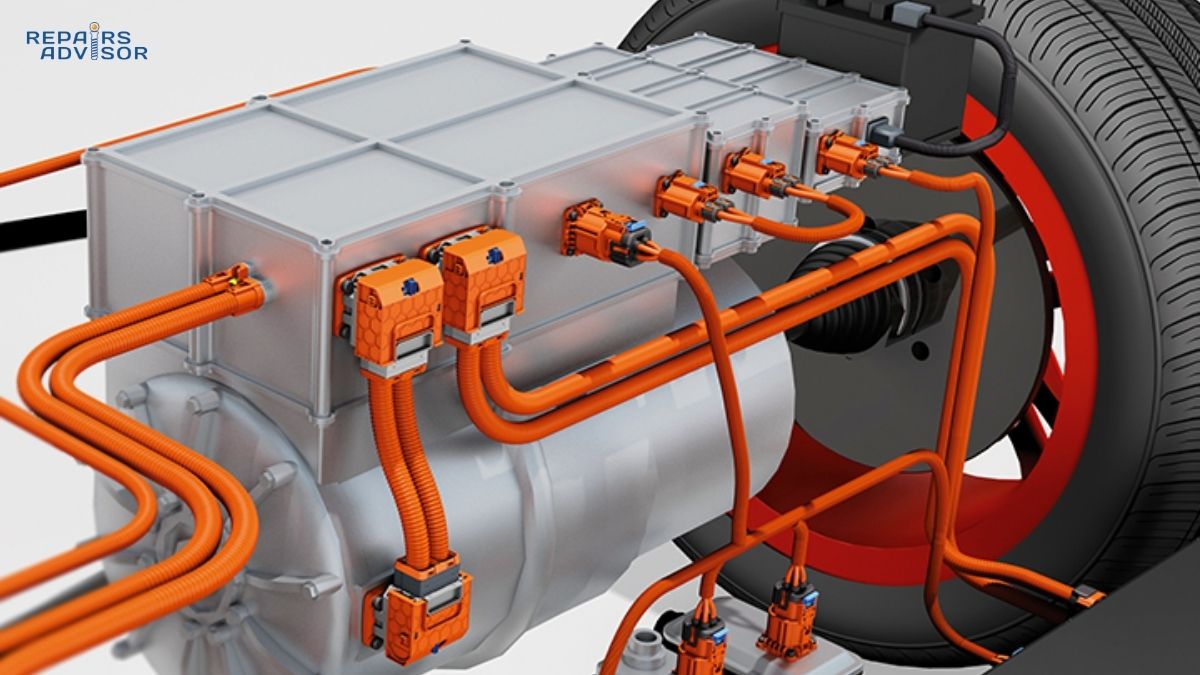

Automotive Ethernet fundamentally changes this equation through its single twisted pair cable design. Where standard Ethernet uses four wires arranged in two twisted pairs, Automotive Ethernet achieves full duplex communication over just one twisted pair—two wires total. This seemingly simple change reduces cable weight by approximately 30% compared to traditional automotive harnesses. Industry estimates suggest connectivity costs drop by up to 80% when switching from legacy networks to Automotive Ethernet. For electric vehicles where every kilogram directly impacts driving range, this weight reduction proves particularly critical. A lighter wiring harness means more range from the same battery capacity or the ability to use a smaller, lighter battery for the same range.

The cost benefits extend beyond raw materials. A unified network architecture dramatically simplifies vehicle manufacturing. Instead of routing separate harnesses for CAN bus, LIN bus, multimedia networks, and diagnostic connections, engineers design a single Ethernet backbone connecting all systems. This consolidation reduces the complexity of harness design, simplifies installation procedures, cuts training time for assembly line workers, and reduces the inventory of different cable types and connectors. The modular nature of Ethernet also enables easier customization—adding features like additional cameras or sensors requires connecting to the existing network rather than designing entirely new harness branches.

These advantages compound over a vehicle’s production lifetime. Automotive Ethernet’s scalability means that as bandwidth requirements increase with new features or software updates, the physical infrastructure remains unchanged. The network can support future enhancements without requiring new wiring harnesses, making the vehicle more adaptable and extending its useful life. This future-proofing characteristic becomes increasingly valuable as vehicles transition toward software-defined architectures where features can be added or updated remotely.

Scalability for Future Technology

Automotive Ethernet’s true power lies in its proven scalability—a characteristic inherited from its data center origins but adapted for the unique demands of vehicle environments. The technology gracefully scales from entry-level implementations to cutting-edge autonomous systems, making it equally viable for basic passenger cars and advanced robotaxis.

Current production vehicles already demonstrate Automotive Ethernet’s versatility across multiple applications. ADAS systems rely on it for sensor communication, connecting forward-facing radar for adaptive cruise control, side-mounted radar for blind spot monitoring, and multiple cameras for lane keeping, automatic emergency braking, and surround view parking assistance. High-resolution infotainment systems leverage Ethernet bandwidth to deliver crisp displays, responsive touchscreens, and seamless smartphone integration. Diagnostic data collection benefits enormously—where traditional OBD-II connections crawl along at serial speeds, Diagnostics over IP (DoIP) via Ethernet enables rapid flash programming, comprehensive data logging, and even remote diagnostics for fleet management. Vehicle-to-everything (V2X) communication, which enables vehicles to share information with each other, infrastructure, and pedestrians, depends on the low latency and high bandwidth Ethernet provides.

Looking forward, Automotive Ethernet becomes absolutely essential for next-generation capabilities. Full autonomous driving at Level 4 and 5 requires processing massive data streams from dozens of sensors simultaneously with guaranteed latency bounds—something only Ethernet with Time-Sensitive Networking extensions can deliver reliably. Over-the-air software updates will expand beyond simple infotainment patches to comprehensive system upgrades affecting critical vehicle functions, demanding secure, high-speed data transfer. Cloud connectivity and remote monitoring enable new business models like predictive maintenance, usage-based insurance, and vehicle health diagnostics—all requiring robust, always-on network connectivity. Advanced artificial intelligence processing, whether distributed at the edge in sensor nodes or centralized in powerful domain controllers, needs the bandwidth to shuffle enormous neural network models and training data.

The automotive industry recognizes this trajectory. Major manufacturers including BMW (an early pioneer who deployed Ethernet in 2008), Volkswagen, Tesla, Mercedes-Benz, General Motors, and virtually every other major OEM have committed to Ethernet-centric architectures for their next-generation vehicles. The OPEN Alliance (One-Pair EtherNet), founded in 2011, has grown to over 400 member companies working to standardize and promote automotive Ethernet adoption. This industry-wide momentum ensures continued investment in the technology, driving down costs and expanding capabilities.

For deeper understanding of the advanced systems enabled by this infrastructure, explore our guides on automotive radar technology, automotive LiDAR systems, and automotive camera vision processing.

Automotive Ethernet Physical Layer & Hardware Components

Single Twisted Pair Technology (100BASE-T1 / 1000BASE-T1)

The physical foundation of Automotive Ethernet represents a masterful adaptation of proven technology for the challenging automotive environment. Understanding how it differs from standard Ethernet reveals the engineering that makes it suitable for vehicles.

Standard Ethernet, as deployed in homes and offices, uses four-wire cabling—two twisted pairs within a CAT5e or CAT6 cable. One pair handles transmission, the other handles reception, enabling full duplex communication. This approach works well in controlled indoor environments but proves unnecessarily heavy and expensive for automotive use where cable runs rarely exceed 40 meters and every gram of weight matters.

Automotive Ethernet achieves full duplex communication over a single twisted pair—just two wires. This dramatic simplification reduces cable weight, lowers material costs, and simplifies routing through the tight spaces of a vehicle’s structure. The cable can be either shielded twisted pair (STP) or unshielded twisted pair (UTP) depending on electromagnetic interference requirements. Areas near the engine or other electrically noisy components typically use shielded cable, while protected interior runs may use less expensive unshielded variants.

The IEEE has standardized several Automotive Ethernet physical layer specifications, each optimized for different bandwidth requirements and use cases. 100BASE-T1 (IEEE 802.3bw), ratified in 2015, delivers 100 megabits per second over single twisted pair cable with lengths up to 15 meters. This standard serves the bulk of current automotive applications including most ADAS sensors, standard infotainment systems, and diagnostic connections. 1000BASE-T1 (IEEE 802.3bp), finalized in 2016, provides 1 gigabit per second over single twisted pair for more demanding applications like high-resolution cameras and centralized sensor processing. 10BASE-T1S (IEEE 802.3cg), published in 2020, offers a lower-speed 10 Mbps variant using a multi-drop bus topology rather than point-to-point connections—useful for cost-sensitive applications like replacing LIN bus networks. Multi-Gigabit Ethernet (IEEE 802.3ch), ratified in 2020, delivers 2.5, 5, and 10 gigabits per second for high-speed backbone connections between major domain controllers.

The remarkable data rates achieved over simple two-wire cables result from sophisticated modulation schemes. 100BASE-T1 employs PAM3 (Pulse Amplitude Modulation with 3 levels), encoding data by varying signal voltage among three distinct levels. Higher-speed variants like 1000BASE-T1 use PAM4 (4 levels) to pack more data into each symbol. These multilevel signaling schemes, combined with advanced error correction and equalization techniques, enable reliable high-speed communication even in the electrically noisy automotive environment filled with electromagnetic interference from ignition systems, motor controllers, and switching power supplies.

PHY Transceivers and Components

The physical layer (PHY) transceiver chip forms the critical interface between digital data in an electronic control unit (ECU) and electrical signals on the wire. These specialized integrated circuits handle the complex signal processing required to achieve high data rates reliably.

Modern Automotive Ethernet PHY transceivers integrate multiple functional blocks. The transmit section converts outgoing digital data from the ECU’s Ethernet MAC (Media Access Controller) into precisely shaped analog signals, applies PAM3 or PAM4 encoding, and drives the cable through output drivers designed to meet automotive EMI requirements. The receive section extracts incoming signals from the cable, applies adaptive equalization to compensate for cable characteristics and reflections, recovers the clock from the received signal, performs analog-to-digital conversion, and decodes the PAM symbols back to digital data. Advanced PHYs include built-in diagnostic features that can detect cable faults, measure cable length, and report signal quality metrics.

Ethernet switches form another essential component, routing traffic between multiple network nodes. Unlike the shared bus architecture of CAN where all devices receive all messages, Ethernet switches create dedicated paths between communicating devices. Modern automotive Ethernet switches feature auto-sensing ports that automatically detect whether a connected device supports 10, 100, or 1000 Mbps and adjust accordingly. They maintain MAC address tables mapping each device’s location, perform layer-2 frame forwarding based on destination addresses, support VLAN tagging for network segmentation, and implement quality-of-service queuing to prioritize time-critical traffic over less urgent data.

The environmental requirements for automotive components far exceed typical commercial electronics specifications. Where consumer Ethernet equipment operates comfortably from 0°C to 70°C, Automotive Ethernet transceivers must function reliably from -40°C to +125°C—spanning winter mornings in Alaska to summer afternoons under a vehicle’s hood. They must survive shock and vibration levels up to 4G acceleration, withstand exposure to moisture and automotive fluids, comply with strict electromagnetic interference (EMI) emission limits to avoid disrupting AM/FM radio or other vehicle systems, demonstrate immunity to electromagnetic interference from other vehicle systems, and maintain reliable operation for 10 or more years through hundreds of thousands of miles.

The evolution of Automotive Ethernet began with BroadR-Reach, a proprietary technology introduced by Broadcom in 2011. BroadR-Reach pioneered the single twisted pair approach and proved that high-speed Ethernet could work reliably in vehicles. BMW adopted BroadR-Reach for their 2008 model year vehicles, becoming the first major manufacturer to deploy Ethernet. The success of BroadR-Reach led to IEEE standardization efforts, with the core technology forming the basis for the 100BASE-T1 standard. This standardization proved crucial—while BroadR-Reach was effective, an open standard ensures multi-vendor competition, drives down costs, and guarantees long-term component availability.

Connectors and Cabling

Unlike standard Ethernet with its ubiquitous RJ45 connector, Automotive Ethernet intentionally avoids mandating a specific connector type. This flexibility allows system designers to optimize for each application’s unique constraints regarding space, environmental sealing, vibration resistance, and cost.

Various connector families have emerged for automotive Ethernet applications. Small form factor connectors designed for tight spaces near sensors measure just a few millimeters. Industrial-grade automotive connectors with robust locking mechanisms and environmental sealing suit harsh under-hood applications. Some implementations use existing automotive connector families with additional pins allocated for Ethernet, enabling consolidation where power and Ethernet signals route through a single connector to a sensor or camera module.

Cable characteristics significantly impact performance. Automotive Ethernet cables typically achieve their full rated distance of 15 to 40 meters depending on the specific standard and cable quality. The twist rate (how tightly the pair is twisted) affects both signal integrity and electromagnetic compatibility—tighter twists generally improve high-frequency performance and reduce radiated emissions. Cable shielding, when used, must be properly grounded at both ends to effectively drain away interference. The cable’s impedance, specified at 100 ohms for most automotive Ethernet standards, must remain consistent throughout the length to minimize signal reflections that can cause errors.

Installation practices matter enormously. Sharp bends exceeding the cable’s minimum bend radius can damage internal conductors or affect impedance. Running Ethernet cables parallel to high-current power cables for long distances invites interference. Proper strain relief at connectors prevents mechanical stress from vehicle vibration from eventually breaking connections. These installation considerations make professional routing and installation important for maintaining network reliability.

For broader context on vehicle electrical systems, see our guides on wiring harnesses and power distribution and ECU automotive computer basics.

Network Architecture & Step-by-Step Operation

Star Topology vs. Bus Topology

The network topology—how devices physically connect and logically communicate—fundamentally shapes system behavior. Automotive Ethernet’s star topology with switched infrastructure offers profound advantages over the bus topology used by CAN and other legacy networks.

In a bus topology like CAN, all network nodes connect to a single shared communication channel—literally a pair of wires running the length of the vehicle with each ECU tapping into it. This arrangement proves elegantly simple and highly reliable, but it forces all nodes to share the bus’s total bandwidth. When one node transmits, all others must wait. CAN uses sophisticated arbitration to determine which node gains access when multiple nodes want to transmit simultaneously, but this arbitration creates variable latency—you can never guarantee exactly when a message will be transmitted. As more nodes join the network or data rates increase, the shared bandwidth must be divided among more participants, eventually leading to congestion.

Automotive Ethernet employs a star topology where each device connects point-to-point to an Ethernet switch. A typical vehicle might have multiple switches—perhaps one in the front housing for ADAS sensors and forward cameras, one in the passenger compartment for infotainment and body control modules, and one near the rear for surround view cameras and parking sensors. These switches interconnect through higher-speed backbone links, creating a hierarchical star topology.

This architecture provides dedicated bandwidth for each connection. When a front-facing camera sends data to the ADAS processing unit, that communication happens over a dedicated 1 Gbps link without affecting any other network traffic. Simultaneously, the infotainment system can stream navigation maps over its own link, radar sensors can report target data over their links, and diagnostic tools can read fault codes—all without interference because each pair of communicating nodes has its own virtual pipe through the switch fabric.

The aggregate bandwidth available scales with the number of connections. A switch with eight ports each running at 1 Gbps provides up to 8 gigabits of total throughput if all ports are simultaneously active. Adding another switch doubles this capacity. This scalability means the network can grow to accommodate new sensors, cameras, and features without redesigning the fundamental architecture—just add another switch port or an additional switch.

Ethernet Switches and Routing

Modern automotive Ethernet switches function as sophisticated traffic directors, making microsecond-level decisions about where to forward each frame of data. Understanding their operation reveals how vehicles achieve the complex communication patterns required by ADAS and autonomous driving systems.

When an Ethernet frame arrives at a switch port, the switch examines the destination MAC (Media Access Control) address—a unique 48-bit identifier assigned to every Ethernet device. The switch consults its MAC address table, which maps each known address to a specific port. If the destination is known, the switch forwards the frame only to that port, creating an efficient point-to-point connection. If the destination is unknown—common when a device first joins the network—the switch floods the frame to all ports except the one it arrived on, then learns the correct port when the destination responds.

This layer-2 switching provides the foundation, but automotive applications require more sophisticated features. Virtual LAN (VLAN) support allows logical network segmentation even over shared physical infrastructure. A vehicle might use separate VLANs for safety-critical ADAS traffic, infotainment data, and diagnostic communications. This segmentation improves security by isolating different domains and prevents broadcast storms where misbehaving devices flood the network.

Quality of Service (QoS) mechanisms prioritize time-critical traffic over less urgent data. When a switch port’s output queue fills—perhaps because multiple input ports are simultaneously sending data to the same destination—QoS determines which frames transmit first. Automatic emergency braking commands receive higher priority than infotainment updates. This prioritization becomes critical during network congestion, ensuring that safety systems maintain their required response times even when diagnostic tools are downloading gigabytes of log data.

Modern automotive switches include auto-sensing and auto-negotiation capabilities on each port. When a device connects, the switch and device automatically determine the highest mutually supported speed (10, 100, or 1000 Mbps), configure duplex mode, and enable features like flow control. This plug-and-play behavior simplifies manufacturing and service—technicians don’t need to configure switches manually when replacing components.

The transition to zonal architectures represents the next evolution in automotive networking. Traditional architectures grouped ECUs by function—all braking components on a dedicated network, all body electronics on another. Zonal architectures instead organize by physical location. A front zone gateway aggregates all sensors, cameras, actuators, and lights in the front of the vehicle regardless of their function. This consolidation dramatically reduces wiring length since devices connect to the nearest gateway rather than routing back to a central controller. High-speed Ethernet backbone links connect zone gateways, each of which may contain an Ethernet switch plus additional interfaces for legacy protocols. Some advanced implementations use hardware-based routing where packet forwarding happens in dedicated silicon rather than software, achieving ultra-low latency measured in microseconds rather than milliseconds.

Step-by-Step Data Flow Operation

Following a typical data packet through an automotive Ethernet network illuminates how these systems achieve reliable, low-latency communication under demanding conditions.

Step 1: Data Generation begins when a sensor—perhaps a forward-facing camera—captures new information. The camera’s image sensor converts light into digital data, onboard processors perform initial processing like lens distortion correction and brightness adjustment, and computer vision algorithms may extract features like lane markers or vehicle detections. This processed data must reach the central ADAS ECU for sensor fusion and decision-making. The camera’s Ethernet MAC controller packages the data into one or more Ethernet frames, each with a header containing source and destination MAC addresses, VLAN tags indicating this is ADAS safety traffic, and priority markers for QoS handling.

Step 2: PHY Layer Transmission converts these digital frames into electrical signals suitable for transmission over the twisted pair cable. The camera’s PHY transceiver accepts outgoing frames from the MAC, serializes the data into a continuous bit stream, applies PAM3 encoding to convert bits into three-level voltage symbols, shapes these symbols with precise timing and amplitude, and drives the resulting analog signal onto the transmit pair. Because Automotive Ethernet uses full duplex communication, the PHY simultaneously receives incoming signals from the same wire pair using sophisticated echo cancellation techniques to separate the incoming signal from the much stronger outgoing signal.

Step 3: Switch Processing happens when the signal arrives at the nearest Ethernet switch, likely mounted in the front zone gateway. The switch’s PHY receives the analog signal, converts it back to digital frames, and passes it to the switching fabric. The switch examines the destination MAC address, consults its address table to find that the ADAS ECU connects to port 5, checks the VLAN tag to verify this traffic is authorized on that port, examines the priority marker and places the frame in the appropriate QoS queue, and when port 5’s transmit queue reaches the front of the line, forwards the frame out that port. Modern switches perform this entire process in just a few microseconds.

Step 4: Multi-Hop Routing may occur if the camera and ADAS ECU aren’t on the same switch. The frame might travel from the front zone gateway to a central backbone switch, then to the passenger compartment gateway, and finally to the ADAS ECU. Each switch along this path repeats the address lookup and forwarding process. Time-Sensitive Networking extensions guarantee that even with multiple hops, critical data meets its latency requirements. Hardware-based routing in advanced switches ensures that forwarding decisions don’t add significant delay—packets flow through the switch fabric at wire speed without waiting for software processing.

Step 5: Reception and Processing completes the journey when the ADAS ECU’s PHY receives the signal on its wire pair, converts it back to digital frames, verifies the frame check sequence to ensure no corruption occurred during transmission, and passes valid frames to the MAC controller. The MAC strips off the Ethernet headers, passes the payload data to higher-layer protocols (perhaps UDP/IP packets containing camera image data), and ultimately delivers the information to the ADAS application software. The entire journey from camera sensor to ADAS processing might take just a few milliseconds—fast enough for real-time decision making in emergency situations.

Step 6: Time Synchronization runs continuously in the background using IEEE 802.1AS (generalized Precision Time Protocol, or gPTP). ADAS systems require precise time synchronization because they must correlate data from multiple sensors measuring the same events. If the camera says it detected a pedestrian at timestamp T, and the radar says it detected an object at nearly the same location at timestamp T+1 millisecond, are these the same object or different ones? Without synchronized clocks, you can’t know for certain. IEEE 802.1AS achieves time synchronization accurate to microseconds across the entire vehicle network, enabling confident sensor fusion. A designated grandmaster clock (often in a central gateway) periodically sends timestamp messages, each switch and ECU measures the delay through their hardware, and distributed algorithms compensate for these delays to maintain a consistent time base throughout the network.

Time-Sensitive Networking (TSN)

Standard Ethernet works on a “best effort” basis—it tries to deliver your data promptly but makes no guarantees about timing. This approach works fine for web browsing or file transfers where occasional delays don’t matter. But automotive safety systems demand determinism—absolute guarantees that critical data will arrive within a specified time window every time, without exception.

Time-Sensitive Networking (TSN) is a collection of IEEE 802.1 standards that add deterministic behavior to standard Ethernet. These extensions make Automotive Ethernet suitable for safety-critical applications that previously required specialized networks like FlexRAY.

IEEE 802.1Qbv (Time-Aware Shaper) implements scheduled traffic by dividing time into repeating cycles, perhaps 1 millisecond long, and partitioning each cycle into time slots. Critical traffic like brake commands or steering inputs gets reserved time slots where the switch guarantees no other traffic will interfere. Lower-priority traffic like diagnostic data or infotainment updates uses remaining time slots. This time-division approach provides deterministic latency bounds—you can mathematically prove that a highest-priority frame will always arrive within X microseconds.

IEEE 802.1Qav (Credit-Based Shaper) offers an alternative approach based on bandwidth reservation. Audio and video streams that need consistent bandwidth but can tolerate small variations in timing use credit-based shaping. Each traffic class accumulates credits at a configured rate, and frames can only transmit when sufficient credits are available. This prevents any stream from monopolizing bandwidth while ensuring guaranteed minimum throughput.

IEEE 802.1CB (Frame Replication and Elimination for Reliability) provides redundancy for the most critical traffic. A source can send duplicate copies of critical frames over different network paths. Switches along the path replicate frames at branch points, and the destination eliminates duplicates, keeping only the first arrival. If one network path experiences a failure or delay, the alternate path ensures the message still arrives on time. This technique achieves fault tolerance without requiring redundant ECUs or sensors—just redundant network paths.

IEEE 802.1AS (Timing and Synchronization) ensures all devices share a common time reference as discussed earlier. This precise time base enables the scheduled traffic mechanisms in 802.1Qbv and supports accurate sensor fusion in ADAS applications.

The combination of these TSN standards transforms Ethernet from a best-effort network into a deterministic system capable of supporting safety-critical automotive applications. Brake-by-wire systems, steer-by-wire controls, and active suspension can rely on Automotive Ethernet with TSN just as confidently as they previously relied on FlexRAY. This consolidation allows vehicles to use a single network technology for everything from critical vehicle control to passenger infotainment, simplifying architecture and reducing costs.

For related diagnostic information, see our article on Code U0001 – High Speed CAN Communication Bus which covers troubleshooting network communication issues.

ADAS and Autonomous Vehicle Applications

Camera System Integration

Cameras serve as the eyes of modern driver assistance and autonomous systems, and Automotive Ethernet provides the bandwidth these sensors demand. The evolution from simple rearview cameras to comprehensive vision systems demonstrates why traditional automotive networks proved inadequate.

Entry-level surround view and parking camera systems typically employ four to six cameras strategically positioned around the vehicle. The front bumper camera monitors the area directly ahead during parking, side mirror cameras eliminate blind spots, and the legally-mandated rearview camera shows the area behind when reversing. Each camera captures video at standard definition (640×480) or high definition (1280×720) resolution, applies compression to reduce bandwidth, and streams the result over 100BASE-T1 Ethernet links. Total bandwidth for a complete surround view system runs approximately 100 to 150 megabits per second. The central infotainment or ADAS controller receives these streams, performs real-time image processing to correct lens distortion and perspective, stitches the multiple views into a coherent bird’s-eye view, and displays the result on the dashboard screen. This processing must happen with minimal latency—drivers expect to see real-time video, not delayed images that could cause them to misjudge distances.

Advanced ADAS forward-facing cameras demand considerably more bandwidth and processing power. These sophisticated sensors don’t just capture video—they run computer vision algorithms to detect and classify objects in the vehicle’s path. Lane detection algorithms identify painted lines and road edges for lane keeping assist. Traffic sign recognition extracts text and symbols from regulatory signs. Pedestrian detection uses machine learning models trained on millions of images to identify humans who might step into the roadway. Vehicle detection tracks cars, trucks, motorcycles, and bicycles, estimating their distance, velocity, and trajectory. To perform these tasks reliably, ADAS cameras require high resolution (2+ megapixels), high frame rates (30-60 fps), wide dynamic range to handle bright sunlight and dark shadows simultaneously, and minimal latency from capture to processing.

The bandwidth question for ADAS cameras involves a critical architectural decision: should processing happen at the sensor (edge computing) or centrally after transmission? Compressed video streams of 25-50 Mbps fit comfortably over 100BASE-T1 links, enabling a centralized architecture where cameras transmit compressed video to a powerful central ADAS ECU for processing. However, compression introduces artifacts that can degrade computer vision performance, and latency from compression/decompression adds delay. The alternative—transmitting uncompressed or minimally compressed high-resolution video—requires 1000BASE-T1 gigabit links but preserves full image fidelity for the most accurate perception possible. Some implementations compromise by performing initial feature extraction in smart cameras (detecting lane markers, vehicle bounding boxes, pedestrian locations) and transmitting only these high-level features over lower-bandwidth connections while still sending full video when needed for deep learning or driver display.

Automotive Ethernet’s modularity shines in camera systems. Adding an additional camera view—perhaps a side repeater camera for better blind spot coverage—requires simply connecting another Ethernet drop to the nearest switch. No redesign of the entire harness, no bandwidth allocation conflicts with other systems, no complex integration of a new network segment. This flexibility accelerates development of new features and enables vehicle manufacturers to offer camera systems as options or trim-level upgrades without fundamental electrical architecture changes.

Learn more about vision technology in our comprehensive guide to automotive cameras and vision processing.

Radar and LiDAR Communication

While cameras excel at detailed visual perception, radar and LiDAR provide complementary capabilities that prove essential for robust ADAS and autonomous systems. These sensors also benefit enormously from Automotive Ethernet connectivity.

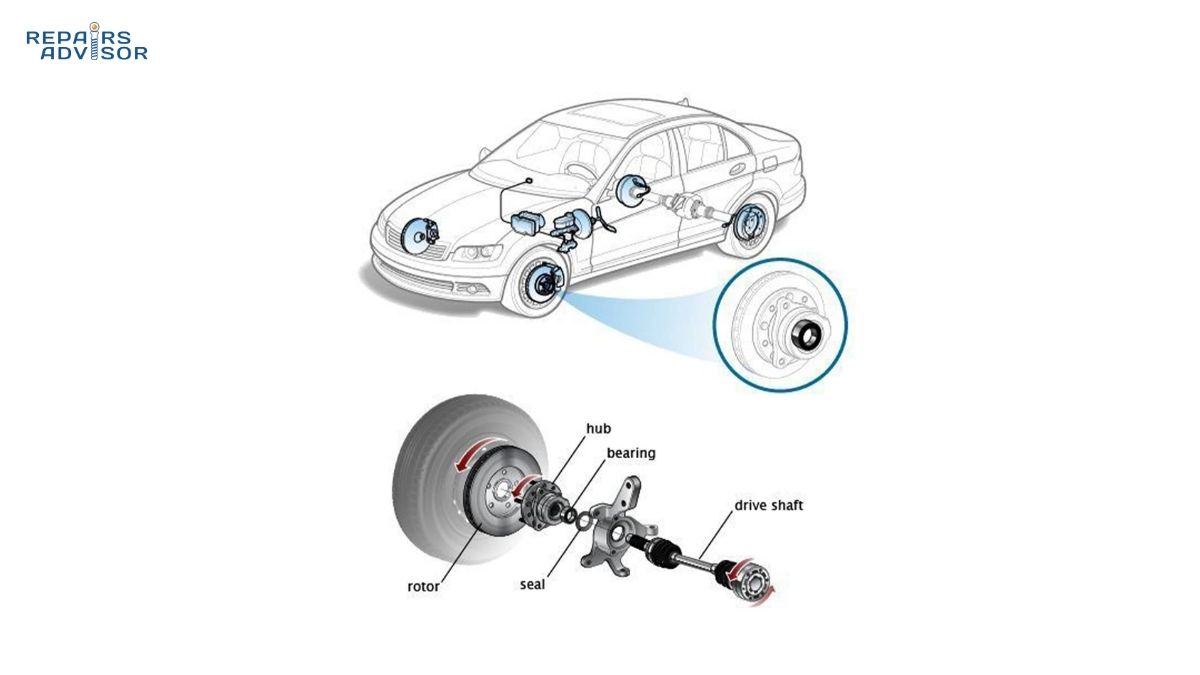

Automotive radar systems typically operate at 77-79 GHz, sending radio frequency pulses and measuring reflections from objects in the environment. Through frequency-modulated continuous wave (FMCW) techniques, radar determines both range (distance to objects) and velocity (speed and direction of movement) with remarkable accuracy. Each radar unit generates a list of detected targets with their ranges, velocities, angles, and radar cross sections. Depending on the radar’s capabilities—short-range parking sensors, medium-range blind spot monitors, or long-range forward-looking units for adaptive cruise control—data output ranges from 10 to 50 megabits per second per radar unit.

Modern vehicles employ multiple radar sensors for complete coverage. A typical ADAS-equipped sedan might include one long-range forward radar (150-250 meter range), two mid-range corner radars for cross-traffic detection, and four short-range parking sensors. Each radar connects to the vehicle network via its own Ethernet link to a zone gateway switch. 100BASE-T1 provides more than adequate bandwidth for current radar data rates. The deterministic latency guarantees of Time-Sensitive Networking ensure that critical radar detections—like a vehicle braking suddenly ahead—trigger immediate responses from the ADAS controller without unpredictable network delays.

LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) generates three-dimensional point clouds by emitting laser pulses and precisely timing their return. A high-resolution LiDAR might emit hundreds of thousands of pulses per second, creating a detailed 3D model of the surrounding environment with centimeter-level accuracy. This extraordinary precision enables autonomous vehicles to perceive the world in ways cameras and radar cannot—detecting the height of obstacles, measuring road surface geometry, distinguishing between a plastic bag blowing in the wind and a actual debris that must be avoided.

The data volumes from LiDAR present significant challenges. A single high-resolution LiDAR scanning at 10-20 Hz (full scans per second) generates 100 to 200 megabits per second of point cloud data. Some autonomous vehicle prototypes employ multiple LiDAR units for redundancy and complete coverage, creating aggregate data rates exceeding 1 gigabit per second. Only Automotive Ethernet provides sufficient bandwidth for this sensor type. Implementations typically use 1000BASE-T1 or even Multi-Gigabit Ethernet (2.5+ Gbps) to ensure the raw point cloud reaches the central perception computer with minimal latency and no data loss.

Sensor fusion—the process of combining camera, radar, and LiDAR data into a unified environmental model—absolutely depends on the time synchronization that Automotive Ethernet with TSN provides. Consider a vehicle detecting a pedestrian. The forward camera sees a human figure at coordinates X, Y in its image plane at timestamp T. The radar detects an object at range R, angle A at timestamp T+0.5 milliseconds. The LiDAR sees a vertical cluster of points at 3D position X, Y, Z at timestamp T+1 millisecond. Are these three detections of the same pedestrian, or three different objects? Only with precise time synchronization can the fusion algorithm confidently correlate these measurements. IEEE 802.1AS time sync accurate to microseconds enables this correlation across sensors that may be meters apart with different processing delays.

The centralized processing ECU for sensor fusion demands extraordinary computing power—often multiple AI accelerator chips capable of trillions of operations per second. This central brain connects to the vehicle’s Ethernet backbone via Multi-Gigabit links, receiving gigabits of combined sensor data, running deep neural networks for object detection and scene understanding, and making split-second decisions about vehicle control. Automotive Ethernet makes this centralized architecture practical.

Explore these technologies further in our guides on automotive radar fundamentals and automotive LiDAR 3D perception.

Infotainment and Diagnostics

While safety-critical ADAS applications drive much of Automotive Ethernet’s adoption, infotainment and diagnostics also benefit significantly from high-bandwidth networking.

Modern in-vehicle infotainment (IVI) systems have evolved into sophisticated multimedia platforms rivaling tablets and smartphones. High-resolution displays—often 10+ inches with 1920×1080 or higher pixel counts—demand considerable bandwidth. Streaming navigation maps with real-time traffic updates, displaying album artwork and video content, rendering 3D animations for the user interface, and supporting multiple simultaneous displays (driver instrument cluster, center screen, passenger entertainment) all contribute to bandwidth demands. Background activities compound this—over-the-air updates downloading in the background, cloud service synchronization, vehicle-to-cloud telemetry reporting. Ethernet’s gigabit speeds handle these demands effortlessly while leaving bandwidth available for more critical systems.

Smartphone integration protocols like Apple CarPlay and Android Auto rely heavily on network bandwidth. Wireless CarPlay, for instance, uses Wi-Fi to mirror the phone’s interface to the vehicle display, stream audio to the vehicle’s speakers, and return touchscreen inputs to the phone. The IVI system needs fast Ethernet connectivity to its wireless access point and sufficient bandwidth to handle multiple simultaneous CarPlay/Android Auto sessions if the vehicle supports separate displays for driver and passenger.

Diagnostics over IP (DoIP) represents a significant advancement over traditional serial-based OBD-II communications. The SAE J1962 diagnostic connector in modern vehicles often includes pins for 100BASE-TX Ethernet connectivity. Professional scan tools connect via this Ethernet port and communicate with vehicle ECUs using the DoIP protocol encapsulated in TCP/IP packets. This approach delivers dramatic improvements over legacy diagnostic protocols that topped out at 500 kilobits per second.

With DoIP over Ethernet, comprehensive vehicle scans that once required minutes complete in seconds. Flash programming—updating ECU software—accelerates from painful hour-long waits to quick 5-10 minute procedures. Detailed data logging for intermittent fault diagnosis captures much more information without missing critical events. Remote diagnostics become practical—a fleet management system can query vehicle health, read fault codes, and analyze performance data from hundreds of vehicles simultaneously over cellular connections.

The security implications of networked diagnostics demand attention. A diagnostic port with IP connectivity provides a potential entry point for malicious actors. Modern vehicles implement MACsec (IEEE 802.1AE) encryption and authentication on diagnostic ports, challenge-response sequences to verify legitimate diagnostic tools, and intrusion detection systems that monitor for unusual network activity patterns. These protections must balance security with the legitimate need for technicians to access vehicle systems during service.

For more on advanced ADAS features enabled by these networks, see our articles on blind spot monitoring side detection, lane departure warning vision processing, and automatic emergency braking collision prevention.

Integration with Legacy Automotive Networks

Mixed Network Architecture

The transition to Automotive Ethernet doesn’t happen overnight. Manufacturers must maintain compatibility with existing components, leverage engineering investments in proven systems, and manage risk during the migration. This reality creates vehicles with heterogeneous networks combining Ethernet and legacy protocols.

A typical current-generation vehicle might deploy Automotive Ethernet for high-bandwidth applications—ADAS sensors, cameras, infotainment systems, and diagnostic access—while retaining CAN, FlexRAY, and LIN for established functions. The powertrain domain often continues using high-speed CAN at 500 kilobits per second, connecting the engine control module, transmission controller, and related sensors. This conservative approach makes sense—these systems work reliably, their timing characteristics are thoroughly validated, and the bandwidth requirements remain modest. Similarly, chassis systems like anti-lock brakes and electronic stability control frequently stick with proven CAN implementations rather than migrating to Ethernet prematurely.

FlexRAY networks persist in premium vehicles with advanced chassis control systems. Steer-by-wire, active suspension with predictive damping, and integrated vehicle dynamics control benefit from FlexRAY’s deterministic time-triggered communication and built-in redundancy. While Automotive Ethernet with TSN can theoretically replace FlexRAY, the re-certification costs and development effort for safety-critical systems encourage manufacturers to maintain existing FlexRAY implementations until complete vehicle redesigns justify the migration.

LIN bus remains the workhorse for low-speed body electronics. Window switches, mirror adjustments, seat controls, interior lighting, and similar functions operate perfectly well at LIN’s 20 kilobits per second. The simplicity and low cost of LIN makes it economically attractive for these applications. Why use an expensive Ethernet PHY when a simple LIN transceiver costing pennies accomplishes the same goal?

Gateway ECUs serve as the critical bridge between these different network domains. A typical gateway might have multiple CAN interfaces (perhaps separate high-speed and low-speed CAN networks), a FlexRAY interface, several LIN master interfaces, and multiple Ethernet ports at different speeds. The gateway’s sophisticated software translates between protocols—converting CAN messages to Ethernet packets, aggregating LIN sensor data for transmission over Ethernet, and routing diagnostic requests from the Ethernet-connected scan tool to the appropriate CAN or FlexRAY network.

This translation isn’t trivial. CAN and LIN use message-based communication where each message has an identifier and up to 8 bytes of data. Ethernet uses frame-based communication with MAC addresses and potentially large payloads. Higher-layer protocols like SOME/IP (discussed next) provide the abstraction layer needed for seamless service-oriented communication across heterogeneous networks. A request for engine temperature might originate from an Ethernet-connected smartphone app, get translated through several layers, and ultimately result in a CAN message query to the engine ECU—all transparently to the requesting application.

AUTOSAR Middleware

AUTomotive Open System ARchitecture (AUTOSAR) provides the software framework enabling this complex multi-network ecosystem to function coherently. AUTOSAR defines standardized software layers separating application code from the underlying hardware and network stack.

The AUTOSAR Classic platform, widely deployed in current vehicles, establishes a layered architecture. At the bottom, device drivers interface directly with hardware—CAN controllers, Ethernet MACs, FlexRAY communication controllers. Above this, the Basic Software layer provides services like communication stack management, diagnostic services, memory management, and operating system functions. At the top, application software implements the actual ECU functionality—fuel injection control, ABS logic, infotainment user interface. Standardized interfaces between layers allow the same application code to run on different hardware platforms with different network technologies.

For Ethernet-connected ECUs, AUTOSAR introduced SOME/IP (Scalable service-Oriented MiddlewarE over IP) as a lightweight alternative to traditional automotive middleware. SOME/IP enables service-oriented architecture where functions expose services that other components can discover and invoke remotely. Instead of hardcoded point-to-point communication paths, applications offer services like “get vehicle speed” or “set cabin temperature,” and other applications find and use these services dynamically. This flexibility perfectly matches Ethernet’s IP-based networking model and enables the software-defined vehicle architectures manufacturers are developing.

AUTOSAR Adaptive Platform extends these concepts for high-performance ECUs running Linux or other POSIX operating systems. These powerful computers—handling sensor fusion, autonomous driving decisions, or complex infotainment features—need more flexibility than the AUTOSAR Classic static configuration allows. Adaptive Platform provides C++ APIs, dynamic application loading, and sophisticated inter-process communication while maintaining compatibility with Classic Platform ECUs through standardized communication mechanisms.

The benefit for Ethernet integration is enormous. Application developers can write code using AUTOSAR services without worrying whether the underlying network uses CAN, FlexRAY, or Ethernet. The middleware handles protocol conversion, discovery, and routing transparently. This abstraction accelerates the transition to Ethernet-centric architectures—engineers can migrate individual ECUs from legacy networks to Ethernet without redesigning all the software that communicates with them.

One-Pair EtherNet (OPEN) Alliance

Standardization efforts through industry alliances have proved essential for Automotive Ethernet’s success. The One-Pair EtherNet (OPEN) Alliance, established in 2011 by BMW Group, Broadcom Corporation, NXP Semiconductors, and Freescale Semiconductor (now part of NXP), coordinates standardization efforts beyond the IEEE specifications.

The OPEN Alliance develops technical specifications complementing IEEE standards. While IEEE focuses on physical layer electrical characteristics and MAC protocols, OPEN addresses higher-layer protocols, conformance testing requirements, and implementation guidelines. The Alliance publishes test specifications defining exactly how to verify that a device correctly implements 100BASE-T1 or 1000BASE-T1. These test specs include parameters like rise time, jitter tolerance, and bit error rates under various conditions. Conformance testing laboratories worldwide use these specifications to certify products.

OPEN also works on protocol stacks for automotive Ethernet. Their specifications for AVB (Audio Video Bridging), TSN protocol profiles, and network management provide implementation guidance ensuring interoperability between different manufacturers’ components. When BMW’s cameras connect to Bosch’s ADAS controllers over Ethernet switches from multiple vendors, OPEN specifications help ensure everything works together.

The Alliance has grown substantially since its founding, now including over 400 member companies spanning automotive manufacturers, semiconductor suppliers, software vendors, and test equipment manufacturers. This broad membership ensures that OPEN standards reflect industry-wide consensus rather than a single company’s preferences. Quarterly plugfest events bring members together to test interoperability between different implementations in realistic configurations.

For troubleshooting network communication issues, see our diagnostic guide on Code U0001 – High Speed CAN Communication Bus which covers symptoms and diagnostic approaches applicable to Ethernet systems as well.

Cybersecurity and Challenges

Security Considerations

Automotive Ethernet’s IP-based architecture introduces cybersecurity challenges largely absent from traditional automotive networks. CAN bus and similar legacy protocols operate as isolated networks with no inherent connectivity beyond the vehicle. They lack the sophisticated addressing, routing, and protocol stacks that make IP networks powerful but also vulnerable.

Ethernet’s TCP/IP foundation brings decades of known security vulnerabilities into vehicles. Attack patterns like man-in-the-middle interception, packet injection, denial-of-service flooding, and protocol exploitation—thoroughly understood in IT networks—now potentially threaten automotive systems. The stakes are considerably higher than in traditional IT security. A hacked laptop might leak personal data or cause financial loss, but a compromised vehicle controller could literally kill people.

Real-world security research demonstrates these risks aren’t theoretical. In 2018, security researchers published findings from their examination of a production automotive Ethernet camera system. Using a compromised ECU on the same network, they successfully injected malicious data into the camera’s video stream being sent to the ADAS processing unit. By carefully crafting false image data, they could potentially trick autonomous emergency braking systems into false activations or, more dangerously, prevent them from detecting actual obstacles. This proof-of-concept highlighted the critical need for authentication and encryption on automotive Ethernet networks.

The industry has responded with multiple security layers. MACsec (IEEE 802.1AE) provides hop-by-hop authentication and encryption at the Ethernet layer. Each frame transmitted on the network includes a cryptographic authentication tag that allows receivers to verify the frame hasn’t been tampered with in transit. Optional encryption prevents eavesdropping on sensitive data. MACsec operates transparently to higher-layer protocols—applications send plain frames, and the Ethernet hardware automatically adds authentication and encryption.

Secure boot mechanisms ensure that ECU firmware hasn’t been modified or replaced with malicious code. When an ECU powers up, it verifies cryptographic signatures on all firmware images before executing them. Any tampered or unsigned code prevents system startup, protecting against persistent malware installations. Over-the-air update systems use similar verification, refusing to install updates that lack valid signatures from the vehicle manufacturer.

Intrusion detection and prevention systems monitor network traffic for suspicious patterns. Unusual communication patterns—an infotainment ECU suddenly sending messages to the brake controller, abnormally high traffic volumes, or protocol violations—trigger alerts and potentially automatic countermeasures like network isolation. These systems must distinguish legitimate traffic variations from actual attacks without false positives that could disable vehicle functions.

Network segmentation using VLANs and firewalls limits attack surface. Safety-critical ADAS traffic operates on separate VLANs from infotainment systems. Firewall rules prevent infotainment components from initiating communications to vehicle control systems. Even if an attacker compromises the infotainment head unit through a malicious smartphone app, proper segmentation prevents that foothold from extending to critical systems.

The ISO/SAE 21434 standard “Road vehicles — Cybersecurity engineering” establishes requirements for automotive cybersecurity throughout the vehicle lifecycle. Published in 2021, it mandates threat analysis, security-by-design practices, vulnerability management, and incident response planning. Compliance with ISO 21434 is increasingly required by manufacturers and will likely become legally mandated in many markets.

Implementation Challenges

Beyond security, Automotive Ethernet faces several technical and economic challenges that affect deployment strategies and timelines.

Achieving deterministic real-time behavior presented one of the biggest technical hurdles. Standard Ethernet’s “best effort” delivery suited office networks but couldn’t guarantee the microsecond-level timing that safety-critical automotive systems demand. Time-Sensitive Networking standards address this limitation, but implementing TSN adds complexity and cost to switches and endpoints. Not all applications require TSN—simple camera feeds for display purposes work fine with standard Ethernet—but identifying which paths need determinism and properly configuring TSN scheduling requires sophisticated network planning tools and expertise.

Integration with legacy networks creates gateway complexity. A gateway ECU bridging between Ethernet, multiple CAN networks, FlexRAY, and LIN requires powerful processors to handle protocol conversion at high message rates without introducing excessive latency. The gateway software must maintain synchronized states across different network domains, handle error conditions gracefully (what happens if the Ethernet switch fails but the CAN networks remain operational?), and provide diagnostic visibility into all connected networks. Developing and validating this complex software represents a significant engineering investment.

Component costs, while dropping steadily, still exceed legacy network transceivers. A basic CAN transceiver costs under one dollar in volume. Early Automotive Ethernet PHY chips cost ten times that or more, though prices have fallen to the $3-5 range as volumes increased. For a vehicle deploying dozens of Ethernet endpoints, these costs add up. Manufacturers must weigh higher component costs against reduced wiring costs and the long-term advantages of future-proof architecture.

Electromagnetic compatibility testing requirements are stringent. Automotive Ethernet devices must pass radiated emissions testing to ensure they don’t interfere with AM/FM radio, GPS, cellular, or other vehicle systems. They must demonstrate immunity to interference from engine ignition systems, motor controllers, and the numerous switching power supplies throughout the vehicle. Passing these tests often requires multiple PCB revisions, adding time and cost to development. The single twisted pair cable must be carefully routed away from noise sources and properly shielded when necessary.

Functional safety certification under ISO 26262 adds another layer of complexity for safety-critical applications. Any Ethernet component in the path of safety-relevant data—PHY transceivers, switches, gateway ECUs—must be developed and validated according to ISO 26262 processes. This includes extensive hazard analysis, requirements tracking, design reviews, static code analysis, comprehensive testing, and documentation sufficient to demonstrate compliance to independent assessors. The resulting ASIL (Automotive Safety Integrity Level) certification process can add years to development timelines and substantially increases costs.

ADAS calibration requirements introduce service challenges. Camera-based systems require precise calibration after any service that could affect sensor positioning—windshield replacement, bumper repair, wheel alignment. Radar systems need calibration to account for mounting tolerances and environmental variations. Professional calibration equipment costs tens of thousands of dollars and requires significant training to operate correctly. The proliferation of ADAS features increases calibration requirements and raises questions about whether independent repair shops can maintain these vehicles or if they become dealer-service-only.

Important Safety Note: Modern ADAS systems with Automotive Ethernet connectivity require professional service and calibration. Attempting DIY repairs on camera mounts, radar sensors, or related systems can compromise safety-critical functions. Improper calibration may cause automatic emergency braking to fail when needed or activate inappropriately, lane keeping assist to steer incorrectly, or adaptive cruise control to misjudge distances. Always consult qualified technicians with proper calibration equipment for any ADAS-related work.

Long-term reliability requirements add final validation hurdles. Automotive components must function reliably for 10-15 years through hundreds of thousands of miles in environments ranging from desert heat to arctic cold, withstanding vibration, moisture, and thermal cycling that would quickly destroy consumer electronics. Proving this level of reliability requires extensive accelerated life testing and multi-year field validation before manufacturers confidently deploy new technology across their entire vehicle lineup.

For more information on electrical system troubleshooting and vehicle communication networks, visit our Vehicle Communication Networks category page.

Location and System Architecture in Vehicles

Physical Placement

The physical architecture of Automotive Ethernet networks mirrors the zonal approach many manufacturers are adopting for overall vehicle electrical systems. Understanding typical component placement helps technicians locate devices during service and reveals design considerations driving implementation decisions.

Ethernet switches typically integrate into zonal gateway ECUs rather than existing as standalone boxes. A typical modern vehicle might have three to five zone gateways strategically positioned. The front zone gateway, often mounted behind the grille or radiator support, aggregates connections from forward-facing ADAS sensors—the long-range radar, front cameras, and occasionally a front-mounted LiDAR unit. This placement minimizes cable runs from sensors to the gateway, reducing weight and simplifying installation. The gateway includes multiple Ethernet switch ports (perhaps 4-8) running at mixed speeds—some 100BASE-T1 for radars and standard cameras, one or more 1000BASE-T1 for high-resolution cameras or sensor fusion data uplinks.

The passenger compartment zone, typically housed in or near the instrument panel, connects infotainment displays, the driver information cluster, telematics modules, and diagnostic port access. This gateway handles considerable bandwidth—high-resolution displays, streaming audio, smartphone integration, and diagnostic communications. It typically connects to the vehicle’s Ethernet backbone with Multi-Gigabit links (2.5 or 10 Gbps) to handle aggregate traffic from multiple displays and data-intensive applications.

Rear zone gateways, mounted near the trunk or rear hatch area, serve surround-view cameras, parking sensors, and increasingly, rear-facing ADAS sensors for highway assist features. Some implementations include side zone gateways in the B-pillars or under the rear seats, connecting side-mounted radar and cameras for blind spot monitoring and cross-traffic detection.

The backbone connecting zone gateways runs through the vehicle’s main wiring harness channels, typically alongside power distribution cables. Engineers carefully plan routing to avoid electromagnetic interference sources—running Ethernet cables parallel to high-current motor power cables invites problems. Physical separation, shielded cabling, or routing through different harness branches mitigates interference.

Individual sensor connections demonstrate Automotive Ethernet’s installation advantages. A typical camera installation might use a combined power-and-data connector carrying 12V power and the Ethernet twisted pair in a single small connector. The cable routes through existing harness channels to the nearest zone gateway, often requiring just 1-2 meters of cable versus the much longer runs traditional architectures demanded to reach central controllers. This distributed approach reduces both cable weight and installation labor.

Environmental protection varies by location. Under-hood components—the front zone gateway and any sensors mounted in the engine compartment—require sealed enclosures rated for high temperature (125°C), exposure to moisture, road salt, and engine chemicals. Interior components operate in much gentler conditions and can use less expensive packaging. Underbody components require rugged enclosures protecting against rock impacts, water spray, and road debris.

Access for Diagnostics

Modern vehicles increasingly provide diagnostic access via Ethernet rather than traditional CAN-based OBD-II protocols. This transition affects service procedures and tool requirements.

The OBD-II diagnostic connector under the dashboard often includes pins allocated for Ethernet. SAE J1962 (the OBD-II connector standard) defines pin assignments for various protocols, and recent additions include 100BASE-TX Ethernet typically on pins 8 and 12. Some manufacturers use different pins or provide a separate connector for Ethernet diagnostic access. Unlike the 100BASE-T1 single twisted pair used throughout the vehicle, the diagnostic port typically uses standard 100BASE-TX with two twisted pairs, allowing connection via standard Ethernet cables and interfaces.

Diagnostics over IP (DoIP, defined by ISO 13400) provides the protocol framework. DoIP encapsulates traditional UDS (Unified Diagnostic Services) messages within TCP/IP packets transported over Ethernet. This approach maintains compatibility with existing diagnostic procedures while leveraging Ethernet’s speed advantages. A technician connects a professional scan tool to the diagnostic port, the tool establishes a TCP connection to the vehicle’s gateway ECU, and diagnostic requests flow as IP packets.

The performance benefits are dramatic. Flash programming an ECU with 32 megabytes of new software over traditional CAN-based diagnostics might require 30-60 minutes. Over DoIP via Ethernet, the same update completes in 5-10 minutes. Comprehensive system scans reading data from dozens of ECUs accelerate from minutes to seconds. Live data streaming for analyzing intermittent faults can capture much higher resolution data without overwhelming the diagnostic interface.

Security considerations affect diagnostic access. Vehicles implement challenge-response authentication requiring the scan tool to prove authorization before accessing security-critical functions like flash programming or calibration. Some manufacturers require secure gateways—online verification through the manufacturer’s servers confirming the technician’s credentials and tool authorization. These measures prevent unauthorized modifications while ensuring legitimate service providers can perform necessary work.

Remote diagnostic capabilities leverage Ethernet connectivity combined with the vehicle’s telematics system. Fleet managers can query vehicle health, read fault codes, access live data, and even trigger certain diagnostic tests remotely over cellular connections. The vehicle’s telematics module acts as an Ethernet-to-cellular gateway, providing secure access to authorized remote users. This capability enables predictive maintenance—identifying developing problems before they cause breakdowns—and reduces unnecessary service visits by pre-diagnosing issues before the vehicle reaches the shop.

Network configuration visibility is another diagnostic benefit. Professional scan tools can display the vehicle’s Ethernet network topology, showing which devices are connected, at what speeds, with what link quality metrics. This visibility accelerates troubleshooting when network issues occur. If an ADAS camera isn’t responding, the technician can verify whether the camera is detected on the network, check link status and negotiated speed, examine error counters for cable quality issues, and pinpoint whether the problem lies in the sensor, cable, switch, or software configuration.

Service Considerations: Working on modern vehicle networks requires professional-level diagnostic tools and training. Consumer-grade OBD-II scan tools often lack Ethernet DoIP support and cannot access many modern vehicle systems. ADAS calibration absolutely requires specialized equipment—laser targets, reflective markers, alignment fixtures, and calibration software—typically representing $20,000-50,000 investments. These tools must be regularly updated as manufacturers release new vehicles with different calibration procedures. Independent repair shops considering ADAS service must carefully evaluate whether the equipment investment and ongoing training costs justify the business opportunity.

Safety Reminder: All service procedures affecting ADAS sensors, mounts, or calibration must be followed precisely according to manufacturer specifications. Improper calibration can cause systems to activate inappropriately or fail to activate when needed—both scenarios create serious safety risks. When in doubt, refer the vehicle to a facility with proper calibration equipment and manufacturer training.

For more information on related electrical systems, see our Electrical Function category page with comprehensive guides on automotive electrical components and troubleshooting.

Conclusion

Automotive Ethernet represents one of the most significant technological shifts in vehicle networking history, fundamentally transforming how modern vehicles handle the massive data demands of advanced safety systems, autonomous features, and connected services. Its advantages over legacy networks are compelling—scalable bandwidth ranging from 100 megabits to 10+ gigabits per second, single twisted pair cabling that reduces weight by 30% and connectivity costs by up to 80%, unified network architecture simplifying vehicle electrical systems, and proven technology adapted from decades of Ethernet evolution in data centers and telecommunications.

The technical foundation enabling these benefits combines multiple innovations. The 100BASE-T1 and 1000BASE-T1 physical layer standards adapted Ethernet for automotive environmental requirements while reducing cabling complexity. Time-Sensitive Networking extensions transformed “best effort” Ethernet into a deterministic platform suitable for safety-critical applications. Full duplex communication over single twisted pairs achieves high data rates in lightweight packaging. Star topology with intelligent Ethernet switches provides dedicated bandwidth for each connection, eliminating the shared-medium limitations that constrain CAN bus and similar legacy networks.

Real-world deployment validates Automotive Ethernet’s capabilities. Major manufacturers including BMW, Volkswagen, Tesla, Ford, General Motors, and virtually every other automotive OEM have integrated Ethernet into their vehicle architectures. BMW led adoption, deploying Ethernet in production vehicles starting in 2008 and steadily expanding its use across their lineup. Current vehicles from multiple manufacturers rely on Ethernet for ADAS sensor connectivity, high-resolution camera systems, gigabit-bandwidth sensor fusion processing, infotainment systems with 4K displays and streaming capabilities, and fast diagnostic access via DoIP. As Level 2+ autonomous features become standard and Level 4-5 autonomy approaches commercialization, Automotive Ethernet provides the essential backbone supporting multi-gigabit data flows from dozens of sensors.

The transition from legacy networks continues gradually, with heterogeneous architectures mixing Ethernet and traditional protocols. Gateway ECUs bridge between domains, enabling new Ethernet-based ADAS systems to coexist with proven CAN-based vehicle control, established FlexRAY chassis systems, and cost-effective LIN bus body electronics. AUTOSAR middleware and SOME/IP protocols provide abstraction layers allowing seamless service-oriented communication across different network technologies. This measured transition approach manages risk while enabling rapid innovation where it matters most.

When to Seek Professional Service

The sophistication of modern Automotive Ethernet systems places them firmly in professional service territory. Unlike basic vehicle maintenance that many enthusiasts can confidently tackle, ADAS systems and vehicle networks demand specialized knowledge, expensive equipment, and rigorous calibration procedures.

DIY limitations are significant and safety-critical. Automotive Ethernet diagnostics require professional scan tools supporting DoIP protocol, often costing $5,000-15,000 with annual software subscriptions adding thousands more. ADAS calibration equipment represents $20,000-50,000 investments including laser alignment systems, reflective calibration targets, precision positioning fixtures, and manufacturer-specific calibration software. Camera systems require sub-degree accuracy in mounting angle and position—alignment that can only be verified with proper equipment. Radar calibration involves setting precise detection patterns and validating performance through test procedures requiring specialized tools. Network configuration and troubleshooting often demands understanding vehicle-specific Ethernet topologies, VLAN configurations, and protocol implementations that vary between manufacturers and model years.

Professional service provides essential advantages beyond equipment access. Trained technicians understand the interdependencies between systems—how replacing a windshield affects camera calibration, how wheel alignment impacts radar beam angles, how ECU software updates might require companion calibrations. They have access to manufacturer technical service bulletins describing known issues, revised procedures, and software updates. Their calibration equipment receives regular updates supporting new vehicle models and revised procedures. Most critically, they accept liability for work performed—when warranty claims or safety concerns arise, professional documentation and proper procedures provide essential protection.

Warranty considerations also favor professional service. Many manufacturers require documented proof of proper ADAS calibration to maintain warranty coverage on safety systems. Using non-manufacturer-approved procedures or equipment may void warranties, leaving owners responsible for expensive system failures. When accidents occur, failure to properly maintain or calibrate ADAS systems could affect insurance claims or even expose owners to legal liability.

Safety Reminder: Modern vehicle networks control safety-critical systems including automatic emergency braking, lane keeping, adaptive cruise control, and electronic stability control. These systems make split-second decisions that can mean the difference between a safe stop and a collision, between maintaining lane position and veering into traffic. Compromised calibration doesn’t just mean a system doesn’t work—it can mean systems behave unpredictably or provide false confidence while failing to protect you. Always consult qualified professionals for any service involving ADAS components, vehicle network systems, or safety-critical electronics. The cost of professional service is trivial compared to the value of properly functioning safety systems.

For related information on advanced driver assistance technologies, see our comprehensive guides on parking assist automated maneuvering and ultrasonic sensors for short-range detection.

The future of automotive networking is clearly Ethernet-centric. As vehicles continue their evolution toward software-defined architectures with over-the-air updates, cloud connectivity, and increasing autonomy, the bandwidth, flexibility, and proven scalability of Automotive Ethernet make it the inevitable foundation for next-generation vehicle electronics. Understanding how these systems work provides valuable insight into modern automotive technology and the connected, autonomous vehicles rapidly approaching mainstream adoption.