⚠️ HIGH VOLTAGE WARNING: Traction motors operate at dangerous voltages (200-800V DC). This article is for educational purposes only. Never attempt DIY diagnosis or repair of traction motor systems. Only certified high-voltage technicians should service electric vehicle propulsion systems. Improper work can result in electrocution, fire, or expensive damage.

Why Traction Motor Is Critical for Electric Vehicle Operatio

A traction motor is a specialized electric motor designed to convert electrical energy into mechanical propulsion for vehicles, including electric cars, hybrids, and locomotives. Unlike standard industrial motors, traction motors handle the unique demands of vehicle propulsion: frequent start-stop cycles, high torque delivery at low speeds, and operation across an extremely wide speed range from zero to over 15,000 RPM.

The performance advantages of traction motors over internal combustion engines are substantial. Modern traction motors achieve efficiency rates exceeding 85-90%, compared to the 20-30% efficiency typical of gasoline engines. This means more of the battery’s stored energy converts directly into motion rather than being lost as heat. Traction motors also deliver instant torque from zero RPM, providing the immediate acceleration response that gives electric vehicles their characteristic performance feel. Power ratings for passenger EV traction motors typically range from 100-250 kW (134-335 horsepower), with some high-performance applications exceeding 300 kW per motor.

The traction motor’s role extends beyond simple propulsion. During deceleration, the motor reverses function and becomes a generator, implementing regenerative braking to capture kinetic energy and return it to the hybrid battery system for storage. This energy recovery can extend vehicle range by 15-30% in urban driving conditions where frequent braking occurs. The motor integrates tightly with the electric motor controller, forming a cohesive propulsion system that responds instantly to driver inputs while managing thermal loads and optimizing efficiency.

When a traction motor fails, the consequences are immediate and severe. Complete motor failure results in total loss of propulsion, leaving the vehicle immobilized. Partial failures manifest as reduced power output, limited acceleration capability, overheating warnings, unusual grinding or whining noises, increased vibration, and decreased efficiency that shortens driving range. Replacement costs are substantial, typically ranging from $3,000 to $8,000 or more depending on vehicle type and motor design, not including the labor required for removal and installation by certified high-voltage technicians.

Quick Facts:

- Function: Convert electrical energy to mechanical energy for vehicle propulsion

- Category: Hybrid & Electric Vehicle Systems

- Maintenance Level: Professional service mandatory (high voltage systems)

- Failure Impact: Complete vehicle immobilization

- Safety Rating: CRITICAL – 200-800V DC high voltage present

Safety Note: Traction motors operate at lethal voltages between 200-800V DC. Only certified high-voltage technicians with specialized training and equipment should diagnose, service, or repair traction motor systems. The high voltage remains present even when the vehicle is turned off until specific isolation procedures are followed. Never attempt DIY repairs on any traction motor components or associated high-voltage systems.

Traction Motor Types and Construction

Understanding the different types of traction motors reveals why manufacturers select specific designs for particular applications. Three primary motor technologies dominate modern electric vehicle propulsion, each offering distinct advantages and trade-offs.

Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors (PMSM)

Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors have emerged as the preferred choice for high-performance electric vehicles. The PMSM construction features permanent magnets mounted on the rotor and sinusoidally-wound copper coils in the stator. When three-phase AC current flows through the stator windings, it creates a rotating magnetic field that synchronizes with the permanent magnet rotor, causing it to spin at precisely the same speed as the rotating field.

The advantages of PMSM technology are compelling. These motors achieve the highest efficiency ratings in the industry, typically 90-95% across a wide operating range. The permanent magnets provide strong magnetic fields without requiring electrical current, eliminating the rotor copper losses that reduce efficiency in other motor types. PMSM motors also deliver the highest power density, meaning they produce more power per kilogram of weight than competing technologies. The sinusoidal back-EMF waveform enables smooth torque delivery without the ripple found in simpler motor designs.

However, PMSM motors come with notable disadvantages. The rare-earth permanent magnets, particularly neodymium-iron-boron alloys, are expensive and subject to supply chain constraints. These magnets can suffer demagnetization at elevated temperatures, typically above 150-180°C, which limits the motor’s thermal operating range. The control system for PMSM motors requires sophisticated Field-Oriented Control (FOC) algorithms to precisely manage the interaction between stator field and rotor position.

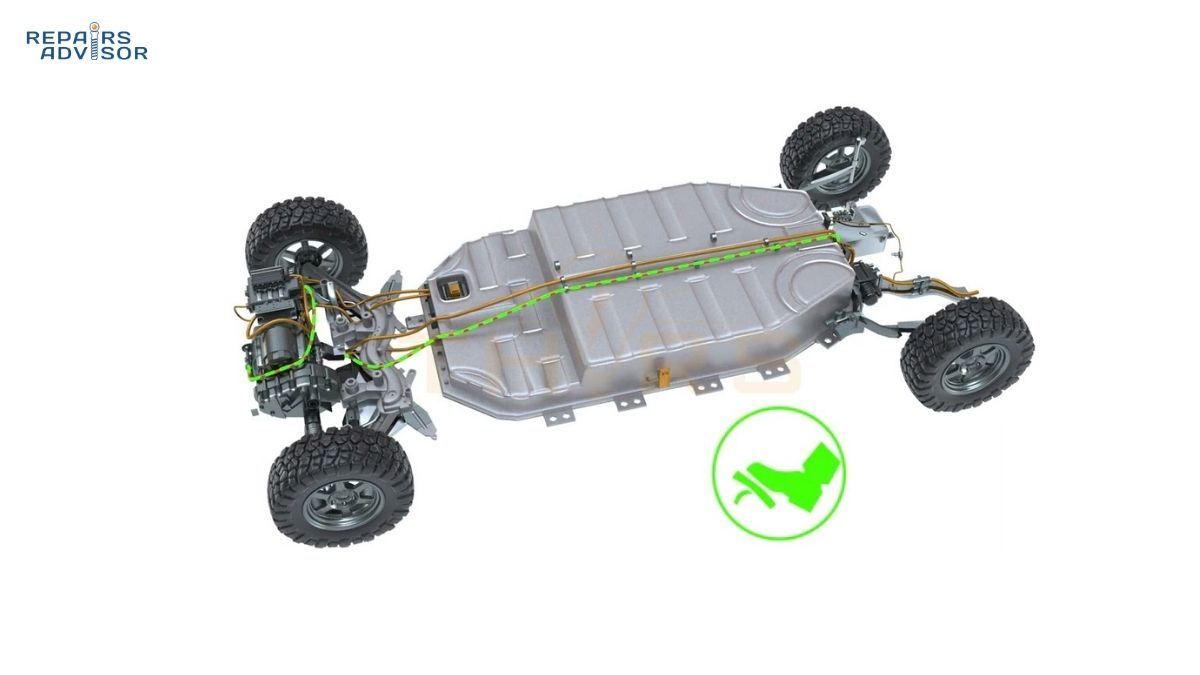

Applications include Tesla Model 3 and Model Y, BMW i3 and i8, Toyota Prius, Nissan Leaf, and numerous other passenger vehicles where efficiency and performance justify the higher cost. The e-axle integration in these vehicles packages the PMSM motor with inverter and gearbox in a compact assembly.

Induction Motors (IM)

Induction motors, also called asynchronous motors, take a different approach to creating rotational motion. The induction motor features a squirrel cage rotor—a cylinder of aluminum or copper bars connected by end rings—with no permanent magnets or electrical connections to the rotor. The stator contains three-phase windings that create a rotating magnetic field when energized. This rotating field induces currents in the squirrel cage rotor bars through electromagnetic induction. The induced currents create their own magnetic field that interacts with the stator field, producing torque.

The key characteristic of induction motors is slip—the rotor always spins slightly slower than the synchronous speed of the rotating stator field. This speed difference is necessary for electromagnetic induction to occur. At typical operating conditions, slip might be 2-5%, meaning if the stator field rotates at 10,000 RPM, the rotor spins at approximately 9,500-9,800 RPM.

Induction motors offer significant advantages. The absence of permanent magnets eliminates concerns about demagnetization and rare-earth material costs. The rugged squirrel cage construction withstands harsh operating conditions, high speeds, and temperature extremes better than motors with permanent magnets. Induction motors excel at high-speed operation, making them suitable for applications requiring extended high-speed cruising. Manufacturing costs are lower since rare-earth magnets aren’t required.

The trade-offs include lower efficiency compared to PMSM motors, typically 85-92% under similar operating conditions. The electromagnetic induction process inherently generates more heat through rotor losses. At low speeds and light loads, efficiency gaps widen further. However, modern control systems have narrowed these efficiency differences substantially compared to older induction motor implementations.

Tesla’s Model S and Model X initially used pure induction motor drivetrains, demonstrating the technology’s viability for high-performance applications. The Audi e-tron also employs induction motors. The thermal management requirements led to sophisticated battery thermal management integration with motor cooling systems.

Brushless DC Motors (BLDC)

Brushless DC motors share similarities with PMSM motors—both use permanent magnets on the rotor and electromagnetic stator windings. The critical difference lies in the back-EMF waveform and control method. BLDC motors feature trapezoidally-arranged permanent magnets that produce a trapezoidal back-EMF waveform, whereas PMSM motors use sinusoidal arrangements.

The trapezoidal commutation used for BLDC motor control is simpler than the FOC required for PMSM motors. A BLDC controller energizes two of the three stator phases at any given moment in a six-step sequence, using Hall effect sensors to detect rotor position and determine when to switch to the next commutation step. This simplicity reduces control system cost and complexity.

BLDC motors deliver high efficiency and excellent torque characteristics, making them popular for applications where cost-effectiveness matters. The simpler control electronics reduce system cost compared to PMSM implementations. However, the six-step commutation creates torque ripple—periodic variations in output torque that cause slight pulsations in power delivery. This torque ripple makes BLDC motors less suitable for applications demanding ultra-smooth operation.

In electric vehicles, BLDC motors commonly power auxiliary systems like electric power steering pumps, cooling fans, and HVAC compressors. In smaller electric vehicles like e-bikes, scooters, and electric motorcycles, BLDC motors provide cost-effective propulsion. The control requirements are simpler than PMSM systems but still provide efficient performance for these applications.

Core Components Shared Across Motor Types

Regardless of the specific motor technology, all traction motors share fundamental components. The stator forms the stationary outer structure, containing copper windings that carry high currents to create the rotating magnetic field. These windings must handle hundreds of amperes while maintaining low resistance to minimize losses. The stator core consists of laminated electrical steel sheets stacked together, with the laminations reducing eddy current losses that would otherwise generate excessive heat.

The rotor is the rotating element at the motor’s center, mounted on the main shaft that connects to the vehicle’s drivetrain. In PMSM and BLDC motors, the rotor carries permanent magnets. In induction motors, the rotor is a squirrel cage of aluminum or copper bars. The housing, typically cast aluminum or steel, provides structural support and incorporates cooling channels for liquid coolant circulation. Modern traction motors almost universally use liquid cooling due to the high power densities involved.

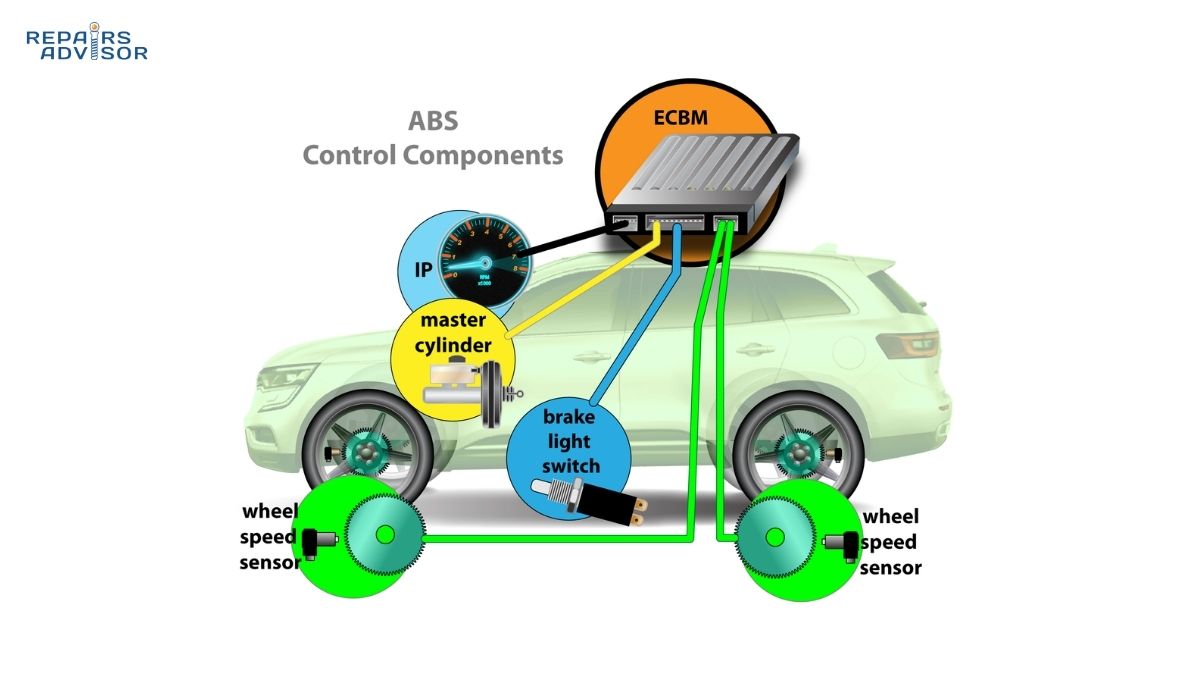

Position sensors, either Hall effect sensors or resolvers, provide real-time rotor position feedback to the motor controller. This information is critical for proper motor control—the controller must know the exact rotor angle to properly time the stator winding energization. The bearings support the rotor shaft, allowing high-speed rotation while handling substantial radial and axial loads. Traction motor bearings must endure harsh conditions: high speeds (up to 18,000 RPM), frequent start-stop cycles, vibration, and wide temperature variations.

The cooling system integrates with the motor housing, circulating liquid coolant through channels in the stator and housing. This coolant absorbs heat generated by copper losses in the windings and iron losses in the magnetic materials, rejecting that heat through a radiator or chiller system. Proper cooling is essential—without adequate heat removal, winding insulation degrades and permanent magnets can demagnetize, leading to motor failure.

How Traction Motors Work – Operating Principles

The process of converting electrical energy from the battery into mechanical rotation involves several precisely-coordinated steps managed by sophisticated power electronics and control systems.

Step 1: Power Flow from Battery

The energy conversion process begins with the high-voltage battery pack, which stores electrical energy at voltages typically ranging from 400V DC in most current electric vehicles to 800V DC in newer high-performance models. The high voltage battery system continuously monitors individual cell voltages, total pack current, and temperature through its battery management system (BMS).

When the driver presses the accelerator pedal, the vehicle’s main computer sends a torque request to the motor controller. Before power can flow to the motor, high voltage contactors must close, creating the electrical connection between the battery and the motor drive system. These contactors are heavy-duty relays capable of switching hundreds of amperes of DC current. A pre-charge circuit gradually energizes the motor controller’s internal capacitors before the main contactors close, preventing the damaging inrush current that would occur if the full battery voltage suddenly appeared across uncharged capacitors.

Safety systems continuously monitor the high-voltage circuit. Isolation monitoring devices check that the high-voltage system remains properly isolated from the vehicle chassis, detecting any insulation faults that could create shock hazards. The HVIL system (High Voltage Interlock Loop) monitors the integrity of high-voltage connectors, immediately shutting down the system if any connector separates unexpectedly.

Step 2: DC to AC Conversion

Traction motors require three-phase AC power to operate, but the battery provides DC. The motor controller, also called an inverter, performs this critical conversion using power electronics. Inside the controller, six IGBT (Insulated Gate Bipolar Transistor) modules arranged in three pairs handle the DC to AC conversion. Each pair of IGBTs controls one of the three motor phases.

The controller uses Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) to synthesize AC waveforms from the DC supply. The IGBTs switch on and off at very high frequencies, typically 10,000-20,000 times per second (10-20 kHz). By precisely controlling the duration that each IGBT remains on during each switching cycle, the controller creates an average voltage that follows a sinusoidal pattern. The switching frequency is high enough that the motor windings, with their inherent inductance, smooth out the chopped waveform into continuous sinusoidal currents.

The controller simultaneously controls both the amplitude and frequency of the AC output. Voltage amplitude determines the strength of the magnetic field and thus the available torque. Frequency determines the speed of the rotating magnetic field and thus the motor’s rotational speed. By varying these parameters in coordination, the controller can produce any combination of torque and speed within the motor’s operating envelope.

This power conversion process generates substantial heat. The IGBTs must switch hundreds of amperes while withstanding voltages up to 800V or more. Each switching event involves a brief moment when the transistor simultaneously conducts current and drops voltage, creating power dissipation. Heat sinks, thermal interface materials, and cooling systems remove this heat to keep the IGBTs within their safe operating temperature range. Advanced controllers integrate DC-DC converters to power the vehicle’s 12V electrical system from the high-voltage battery.

Step 3: Electromagnetic Field Creation

When three-phase AC current flows through the stator windings, it creates a rotating magnetic field—a magnetic field whose poles rotate around the stator’s circumference. This happens because the three windings are physically positioned 120 degrees apart around the stator, and the three-phase currents reach their peaks 120 electrical degrees apart in time.

At any instant, current flows in different directions and magnitudes through the three windings. The combination of these three currents creates a magnetic field that points in a specific direction. As the AC currents progress through their cycles, the direction of this combined magnetic field smoothly rotates around the stator. The speed of this rotation, called synchronous speed, is directly proportional to the AC frequency supplied by the controller.

The strength of the rotating magnetic field depends on the current amplitude flowing through the stator windings. Higher current creates a stronger field, which can exert greater force on the rotor and produce more torque. The motor controller precisely regulates this current based on the torque demanded by the driver and the physical limits of the motor and battery system.

The stator core, made from laminated electrical steel, channels and concentrates this rotating magnetic field. The laminations reduce eddy currents that would otherwise circulate in the steel core, generating heat and reducing efficiency. The copper windings that carry the stator currents must have sufficient cross-sectional area to handle peak currents of 300-600 amperes or more without excessive resistance. Even small resistance in these windings creates I²R losses (power lost as heat proportional to current squared times resistance), so minimizing winding resistance is crucial for efficiency.

Step 4: Rotor Interaction and Torque Generation

The interaction between the stator’s rotating magnetic field and the rotor produces the torque that drives the vehicle’s wheels. The specific mechanism differs between motor types.

In a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor, the permanent magnet rotor is pulled into alignment with the rotating stator field. The north poles of the rotor magnets are attracted to the south poles of the stator field, and vice versa. As the stator field rotates, it continuously pulls the rotor around, maintaining synchronization. The rotor spins at exactly the same speed as the rotating field—hence “synchronous” motor.

The torque produced depends on the angle between the rotor’s magnetic poles and the stator field’s magnetic poles. Maximum torque occurs when these fields are 90 degrees apart electrically. The motor controller uses the rotor position sensor feedback to maintain this optimal angle, a technique called Field-Oriented Control. By keeping the fields at the right angle while varying the stator field strength, the controller achieves precise torque control across the entire operating range.

In an Induction Motor, the process is slightly different. The rotating stator field cuts across the squirrel cage rotor bars, inducing electrical currents in those bars through electromagnetic induction (the same principle used in a transformer). These induced currents create their own magnetic field in the rotor. The interaction between the stator field and the rotor’s induced field produces torque.

For induction to occur, the rotor must spin slower than the synchronous speed of the stator’s rotating field—this speed difference is called slip. If the rotor matched the synchronous speed exactly, no relative motion would exist between the stator field and rotor bars, no induction would occur, and no torque would be produced. Typical slip ranges from 2-5% under normal operating conditions. The amount of slip increases when more torque is demanded, as higher rotor currents (and thus stronger rotor magnetic fields) require stronger induction.

The rotor shaft connects to the vehicle’s drivetrain, typically through a reduction gear system. Traction motors spin at very high speeds—often 12,000-18,000 RPM or more at highway speeds—but vehicle wheels rotate at much lower speeds. A single-speed EV transmission provides a fixed gear reduction ratio, typically between 8:1 and 12:1, converting the motor’s high speed and relatively low torque into the lower speed and higher torque needed at the wheels.

Step 5: Speed and Torque Control

The motor controller continuously adjusts voltage and frequency to deliver the torque requested by the driver while respecting system limitations. The accelerator pedal position translates into a torque demand, but the controller must also consider battery state of charge, motor temperature, inverter temperature, and numerous other factors.

Traction motors operate in two distinct regions. In the constant torque region, from zero speed up to base speed (typically 4,000-6,000 RPM for the motor), maximum torque is available. The controller increases both voltage and frequency proportionally as speed increases, maintaining the magnetic field strength necessary for peak torque. This region provides the strong low-speed torque that gives electric vehicles their impressive acceleration from standstill.

Above base speed, the motor enters the constant power region, also called the field weakening region. The controller has reached the maximum voltage the battery can supply, so as frequency continues increasing to raise motor speed, the current must decrease to maintain constant power. Since torque is proportional to current, this means torque decreases as speed increases above base speed. The ratio of maximum speed to base speed is called the Constant Power Speed Ratio (CPSR), typically 2.5:1 to 4:1 in traction motors. A CPSR of 3:1 means the motor can reach three times its base speed while delivering one-third of its peak torque.

The controller receives feedback from multiple sensors: rotor position sensor for precise field orientation control, temperature sensors in the motor windings and controller power electronics, current sensors measuring the three-phase motor currents, and DC voltage and current sensors monitoring battery power flow. This feedback enables closed-loop control that responds to changing conditions in milliseconds.

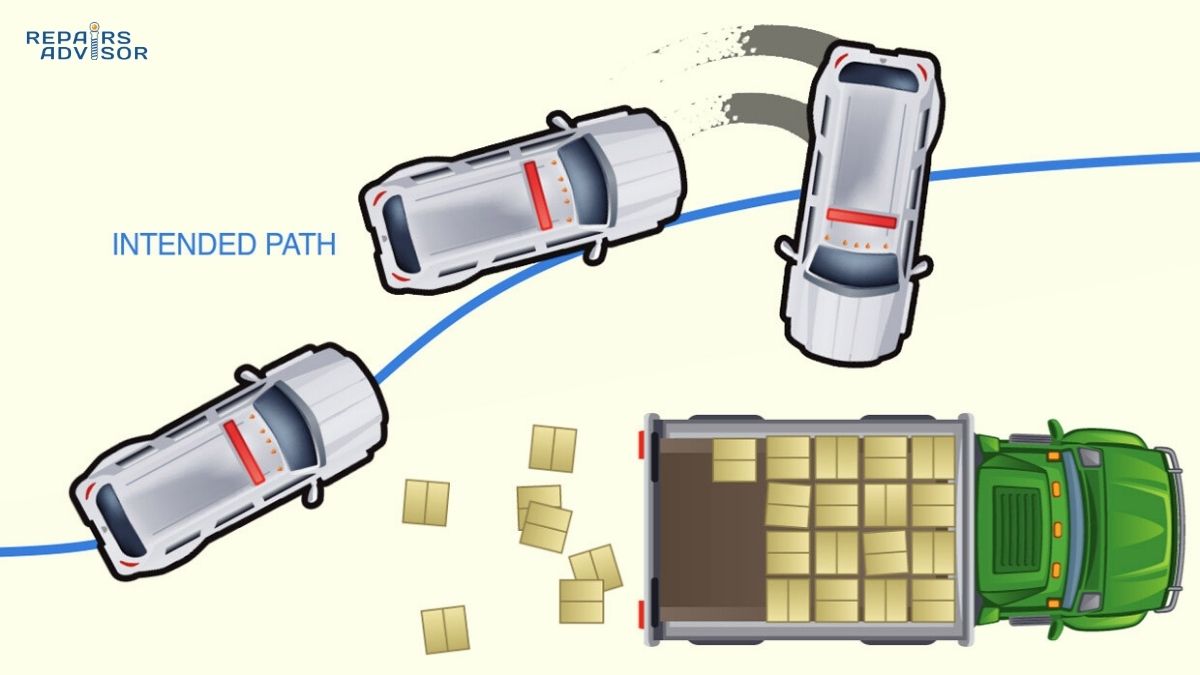

Modern traction motor control systems implement sophisticated algorithms. Torque vectoring on dual-motor all-wheel-drive vehicles varies torque distribution between front and rear motors for optimal traction and handling. Efficiency optimization algorithms adjust the motor’s operating point to minimize losses—sometimes running at slightly reduced torque to improve efficiency, trading small performance reductions for significant range improvements. Integration with vehicle stability control and traction control systems allows the motor controller to modulate torque instantly when wheel slip is detected, far faster than traditional brake-based traction control.

Step 6: Regenerative Braking Mode

When the driver lifts off the accelerator or applies the brakes, the traction motor transitions from propulsion to regeneration mode, becoming a generator that converts kinetic energy back into electrical energy. This regenerative braking capability is one of the most significant advantages of electric propulsion systems.

As the vehicle decelerates, the wheels continue driving the motor through the reduction gears. The motor controller reverses its strategy: instead of driving current through the stator to pull the rotor forward, it now uses the rotor’s motion to generate current in the stator windings. The rotating permanent magnets (in PMSM motors) or the induced rotor currents (in induction motors) create changing magnetic flux through the stator windings. According to Faraday’s law of induction, this changing flux generates voltage in the windings.

The motor controller’s IGBTs now operate as active rectifiers, converting the three-phase AC generated by the motor back into DC current that flows back to the battery. The controller must carefully regulate this process—too little regeneration fails to capture available energy, while too much creates excessive braking force that could destabilize the vehicle or make the brake pedal feel inconsistent.

The amount of regeneration depends on several factors. Vehicle speed affects the regenerative power available—higher speeds generate more voltage and potentially more power. Battery state of charge limits how much energy the battery can accept—a fully charged battery cannot accept additional charge, so regeneration becomes limited or unavailable. Temperature affects both the motor’s ability to generate power and the battery’s ability to accept it. The motor controller coordinates with the friction brake system to blend regenerative and friction braking seamlessly, maintaining consistent brake pedal feel while maximizing energy recovery.

Regenerative braking can recover 60-70% of the vehicle’s kinetic energy during deceleration. In urban driving with frequent stops, this energy recovery can extend driving range by 20-30% compared to relying solely on friction brakes. The recovered energy also reduces brake wear dramatically—brake pads and rotors on electric vehicles often last 100,000 miles or more since the friction brakes handle only a portion of the stopping duty.

Thermal Management Throughout Operation

Heat generation is inherent to motor operation. Copper losses occur whenever current flows through the stator windings—the windings’ electrical resistance converts some electrical power into heat proportional to I²R. Iron losses occur in the stator core as the magnetic field alternates at high frequencies, causing hysteresis losses (energy lost as magnetic domains in the steel flip back and forth) and eddy current losses (circulating currents induced in the steel). Mechanical losses come from bearing friction and air resistance as the rotor spins at high speed.

A liquid cooling system manages these thermal loads. Coolant, typically a 50/50 mixture of water and glycol antifreeze, circulates through cooling channels integrated into the motor housing and stator. An electric coolant pump, separate from the engine cooling system in hybrid vehicles or the sole cooling pump in pure EVs, circulates this coolant through the motor and then through a radiator or chiller where heat is rejected to ambient air or a refrigeration cycle.

Temperature sensors throughout the motor provide feedback to the control system. Winding temperature is critical—copper windings are typically rated to 180-200°C maximum, with insulation materials chosen to withstand these temperatures. If winding temperature approaches limits, the controller implements thermal derating, reducing maximum current and thus maximum torque to prevent overheating. Permanent magnets in PMSM motors have their own temperature limits—exceeding 150-180°C risks irreversible demagnetization that permanently reduces motor performance.

In vehicles with integrated e-axle designs, a single cooling system may handle the motor, inverter, and reduction gearbox. Advanced systems use thermal management strategies that prioritize cooling based on which component is hottest or which is most critical for current operating conditions. Some high-performance applications use refrigerant-based cooling systems similar to air conditioning to achieve lower temperatures than possible with traditional liquid cooling.

Performance Characteristics and Requirements

Traction motors face substantially different operating requirements than industrial electric motors, driven by the unique demands of vehicle propulsion.

Operating Requirements Different from Industrial Motors

Industrial motors typically operate at or near a constant speed and load, running for extended periods at steady-state conditions. Traction motors, in contrast, face wildly varying conditions. Urban driving involves frequent start-stop cycles, with the motor accelerating from zero to moderate speed, running briefly at constant speed, then decelerating back to zero, potentially hundreds of times during a single trip. Each start requires the motor to produce high torque from standstill, and each stop either dissipates energy through friction brakes or recovers it through regenerative braking.

Traction motors must deliver high torque at low speeds for vehicle acceleration and hill climbing. From standstill up to perhaps 40-50 mph, the driver expects strong, immediate acceleration. The motor must produce peak torque throughout this low-speed range. Conversely, at high speeds during highway cruising, the motor operates at lower torque but must sustain that operation for extended periods without overheating.

The speed range requirement is extraordinary. Traction motors operate from zero RPM up to maximum speeds that can exceed 15,000-18,000 RPM in high-performance applications. This represents a far wider operating range than typical industrial motors. Across this entire range, the motor must maintain high efficiency—inefficient operation at any commonly-used speed degrades overall vehicle range and performance.

Efficiency requirements are stringent because every watt of power lost to heat is a watt not available for propulsion, directly reducing vehicle range. Traction motors typically achieve 90-96% efficiency at rated load, maintaining 85%+ efficiency across a wide range of operating points. This level of efficiency, sustained across varying speeds and loads, requires careful design of electromagnetic circuits, minimization of all loss mechanisms, and sophisticated control algorithms.

Packaging constraints are severe. The motor must fit within the limited space available in the vehicle, often integrated into the axle assembly. Weight is critical—every kilogram of motor weight is a kilogram that must be accelerated, decelerated, and carried around, reducing efficiency and performance. Power density, measured in kW/kg, is a key performance metric, with modern traction motors achieving 2-4 kW/kg or higher.

Environmental conditions are harsh. Traction motors must operate reliably across ambient temperature extremes from -40°C in arctic conditions to +50°C in desert environments. Vibration is continuous, with shocks from road irregularities transmitted through the drivetrain. Contamination from road dirt, water spray, and salt is inevitable despite protective housings. The motor must withstand these conditions for the vehicle’s lifetime, typically 150,000-200,000 miles or more.

Typical Specifications for Passenger Electric Vehicles

Understanding specific performance numbers helps illustrate what modern traction motors achieve. A typical traction motor for a mid-size passenger electric vehicle might have these specifications:

Power ratings typically range from 100-250 kW (134-335 horsepower) for single-motor configurations. High-performance vehicles may use dual motors providing combined power exceeding 500 kW. The power rating represents continuous power output the motor can sustain without overheating. Peak power, available for brief periods (typically 30-60 seconds), may be 20-50% higher than continuous rating.

Peak torque ranges from 200-400 Nm (147-295 lb-ft) at the motor shaft. When multiplied by the reduction gear ratio (typically 8:1 to 12:1), this translates to 1,600-4,800 Nm (1,180-3,540 lb-ft) at the wheels—far exceeding the torque of comparable gasoline engines. This abundant torque provides the strong acceleration characteristic of electric vehicles.

Maximum speed typically reaches 12,000-18,000 RPM, though some designs exceed 20,000 RPM. The maximum speed is limited by mechanical constraints (bearing speed limits, rotor balance, centrifugal forces) and electrical constraints (back-EMF voltage limitations).

Efficiency at rated load reaches 92-96% for PMSM motors and 88-94% for induction motors. The efficiency map—showing efficiency across all combinations of speed and torque—reveals that well-designed traction motors maintain efficiency above 90% across much of their operating range, with peak efficiency zones carefully placed where the vehicle spends most time operating.

Voltage systems most commonly operate at 400V nominal, with actual operating voltage ranging from 300-450V depending on battery charge state. Newer high-performance vehicles are adopting 800V systems, which allow higher power transmission with lower currents, reducing resistive losses and enabling lighter, smaller conductors.

Current during peak acceleration can reach 300-600 amperes or more. The motor controller and all connections must handle these high currents without excessive voltage drop or heating. Continuous current rating is lower, typically 150-300 amperes, representing sustained high-power cruise conditions.

Cooling systems use liquid coolant (typically water-glycol mixture) with flow rates of 10-20 liters per minute and coolant temperature targets of 65-70°C. The cooling system must reject heat loads of 10-30 kW during sustained high-power operation, requiring radiator capacity similar to that needed for a comparable internal combustion engine.

Weight for the motor alone (excluding controller and reduction gearbox) typically ranges from 40-80 kg (88-176 lbs) for passenger car applications. The power-to-weight ratio of 2-4 kW/kg represents a significant advantage over internal combustion engines, which rarely exceed 1 kW/kg including their necessary auxiliary systems.

Dimensions vary by design, but a typical traction motor might measure 250-350mm in diameter and 150-250mm in length. The compact size allows integration into the vehicle’s axle assembly, freeing up passenger and cargo space that would be occupied by a traditional engine and transmission.

Common Issues and Maintenance Requirements

Despite their reliability advantages over internal combustion engines, traction motors can experience problems that require professional attention.

Bearing wear represents one of the most common failure modes. The bearings support the rotor shaft while allowing rotation at speeds exceeding 15,000 RPM. Despite using high-quality bearings designed for these speeds, the continuous vibration from road conditions, frequent starts and stops, and the sheer number of rotations accumulated over vehicle lifetime can cause bearing wear. Symptoms include increasing noise (humming, grinding, or whining sounds), vibration that worsens with speed, and eventually rough rotation or binding. Bearing failure can cause catastrophic damage if the rotor contacts the stator.

Winding insulation breakdown occurs when the electrical insulation separating the copper windings degrades. The insulation must withstand both high voltages (phase-to-phase voltages can reach hundreds of volts) and thermal cycling as the motor heats during operation and cools when parked. Over time, this thermal cycling, combined with vibration and contamination, can cause insulation to crack or degrade. Insulation resistance testing can detect degradation before catastrophic failure occurs. Complete insulation failure creates phase-to-phase shorts or phase-to-ground shorts, resulting in immediate motor failure and potential controller damage.

Permanent magnet demagnetization affects PMSM and BLDC motors. If the rotor magnets exceed their Curie temperature (the temperature at which they lose magnetism), typically 150-180°C depending on magnet composition, they can suffer permanent magnetic strength loss. Even operation below this temperature but at elevated temperatures for extended periods can cause gradual demagnetization. High currents during fault conditions can also create demagnetizing magnetic fields strong enough to weaken the permanent magnets. Symptoms include reduced torque output and decreased efficiency.

Rotor imbalance creates vibration that increases with speed. Rotor imbalance can result from manufacturing tolerances, magnet displacement, or damage during service. Precision balancing is required during motor assembly, but damage or improper service procedures can introduce imbalance. Severe imbalance causes vibration, noise, accelerated bearing wear, and potentially catastrophic failure if the rotor contacts the stator.

Coolant system failures manifest as motor overheating. Coolant leaks from failed seals or gaskets reduce coolant volume and allow air into the system. Coolant pump failures stop circulation. Blocked cooling passages restrict flow. External cooling system problems (failed radiator fan, restricted radiator) prevent heat rejection. Any of these conditions can cause motor temperature to exceed safe limits, triggering thermal protection that reduces power output or shuts down the motor completely.

Position sensor failures prevent proper motor control. The controller requires accurate rotor position information to properly time the stator currents. Sensor failures cause rough operation, reduced power, vibration, and error codes. In some cases, the motor may fail to operate at all without position feedback.

Contamination from water, dirt, or debris entering the motor housing can cause multiple problems. Contamination can create electrical paths that lead to shorts, damage bearings by introducing abrasive particles, or block cooling passages. Motor housings are designed with seals to prevent contamination, but seal failures or damage to the housing can allow contamination entry.

Maintenance Requirements and Best Practices

Traction motors require substantially less maintenance than internal combustion engines—no oil changes, spark plugs, timing belts, or valve adjustments. However, proper maintenance is still necessary to ensure long service life.

Coolant system service follows manufacturer-specified intervals, typically every 50,000-100,000 miles or every 4-6 years. The service includes draining old coolant, flushing the system to remove deposits, and refilling with fresh coolant mixed to the correct concentration. Coolant degrades over time, losing its corrosion inhibitors and heat transfer properties. Regular inspection checks for leaks, proper coolant level, and signs of contamination.

Vibration analysis provides early warning of bearing problems or rotor imbalance. Professional technicians use accelerometers to measure vibration frequency and amplitude at various motor speeds. Changes in the vibration signature over time indicate developing problems before they cause failure. This predictive maintenance approach prevents catastrophic failures.

Insulation resistance testing checks the integrity of winding insulation. A megohmmeter applies high voltage (typically 500-1000V DC) and measures the leakage current through the insulation. Decreasing resistance values over time indicate insulation degradation. Testing should occur during regular service intervals and after any motor exposure to moisture or contamination.

Temperature monitoring during operation helps detect developing problems. The vehicle’s built-in temperature sensors provide continuous monitoring, but professional diagnosis may include thermal imaging to identify hot spots that indicate localized problems like poor cooling, winding shorts, or bearing issues.

Visual inspection checks for physical damage, coolant leaks, seal deterioration, housing cracks, connector damage, and any signs of contamination or debris entry. Inspection should occur at regular intervals and after any collision or impact.

Professional diagnostic testing uses specialized equipment to analyze motor performance, controller operation, and system integration. This testing identifies subtle problems that may not yet cause obvious symptoms but could lead to failure if not addressed.

Warning Signs Requiring Professional Attention

Certain symptoms indicate problems requiring immediate professional evaluation:

Reduced power output or limited acceleration suggests motor problems, controller issues, or battery system faults. The vehicle may enter a “limp mode” that limits power to prevent damage. Professional diagnosis determines whether the problem originates in the motor, controller, battery, or connecting systems.

Unusual noises from the motor area demand immediate attention. Grinding noises typically indicate bearing problems. Whining or buzzing sounds may indicate electrical issues. Rattling can suggest loose components or internal damage. Any new or changing noise should be evaluated promptly.

Overheating warnings or temperature fault codes indicate cooling system problems or excessive motor loading. The vehicle may reduce power or shut down to prevent damage. Continuing to operate with overheating warnings risks permanent motor damage.

Vibration or rough operation that worsens with speed suggests bearing wear, rotor imbalance, or mounting problems. Severe vibration can cause accelerated wear throughout the drivetrain.

Efficiency loss manifests as reduced driving range without corresponding changes in driving patterns. While many factors affect range, motor efficiency degradation is one possibility that requires professional evaluation.

Cooling system leaks appear as colored coolant (typically orange or pink) under the vehicle or in the motor area. Any coolant leak requires prompt repair—operating with low coolant risks motor damage from overheating.

Dashboard warning lights specifically related to the propulsion system, motor temperature, or charging system require professional diagnosis. Modern vehicles have sophisticated monitoring systems that detect problems before they cause failure.

Professional Service and Safety Considerations

Working on traction motor systems requires specialized training, equipment, and safety procedures that place these systems firmly in the professional service category.

Critical High Voltage Safety Requirements

The most critical safety consideration with traction motors is the high voltage involved. Traction motors operate at 200-800V DC, with some high-performance systems exceeding 900V. These voltage levels are immediately lethal—contact with high voltage conductors can cause death through electrocution. Even brief contact can cause severe burns from arc flash as current jumps across air gaps.

The high voltage remains present in the system even when the vehicle is turned off. Large capacitors in the motor controller store energy that maintains voltage for minutes or even hours after shutdown. The battery remains connected to the high voltage bus unless specific isolation procedures are followed. Anyone approaching high voltage systems must assume voltage is present until proven otherwise through proper testing procedures.

The high voltage interlock loop provides one layer of protection. This safety circuit monitors the integrity of all high voltage connectors, immediately disconnecting power if any connector separates. Service procedures require disconnecting the HVIL before beginning any high voltage work, and the system prevents motor operation with the interlock open.

Pyro-fuse systems provide emergency disconnection capability. In a severe collision, crash sensors trigger explosive charges that physically sever high voltage cables, isolating the battery from the motor and controller. This prevents electrical fires and protects first responders and rescue personnel.

Before any high voltage work, technicians must follow lockout/tagout procedures. This involves disconnecting the high voltage service disconnect (typically located under the hood or in the trunk), removing the 12V service disconnect to prevent inadvertent system energization, waiting the manufacturer-specified time for capacitor discharge (typically 5-15 minutes), testing to verify voltage is absent using calibrated high-voltage meters, and placing lockout devices and warning tags to prevent anyone from reconnecting power while work is in progress.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) requirements for high voltage work include insulated gloves rated for the system voltage (typically Class 0 or Class 00 gloves rated to 1000V), leather protector gloves worn over insulated gloves, arc-rated face shield to protect against arc flash, arc-rated clothing that won’t ignite from electrical arcs, and insulated tools rated for high voltage work. Standard tools must never be used on high voltage systems.

Insulation resistance testing verifies system safety before energizing after service. A megohmmeter tests the resistance between the high voltage conductors and vehicle chassis (ground). Minimum acceptable resistance typically exceeds 100 ohms per volt (e.g., 40,000 ohms minimum for a 400V system). Lower resistance indicates insulation damage or contamination that could create shock hazards.

Professional Equipment and Training Requirements

Servicing traction motors requires specialized equipment beyond what’s available to DIY mechanics or even general automotive repair shops.

High voltage diagnostic equipment includes multimeters rated for the system voltage (minimum CAT III 1000V rating), oscilloscopes for analyzing motor controller PWM signals and motor current waveforms, motor analyzers that can test motor parameters, insulation resistance and winding resistance, and dedicated scan tools with hybrid/EV capabilities for reading system data and fault codes.

Specialized tools include torque wrenches capable of the high torque values required for motor mounting and high voltage connections, lifting equipment rated for the motor weight (often 50-100 kg for motor plus reduction gear assembly), alignment tools for ensuring proper motor-to-drivetrain alignment, and manufacturer-specific tools for particular vehicles.

The service environment matters. High voltage work should occur in clean, dry conditions. Many procedures require specific temperature ranges. Some procedures require the vehicle to be secure on a lift with specific supports. The 12V electrical system must remain functional during many procedures to operate cooling systems or control modules.

Training requirements are stringent. Technicians working on high voltage systems must complete manufacturer-approved high voltage training, typically classified as Level 2 (qualified person) or Level 3 (electrically skilled person) depending on the scope of work. This training covers electrical theory, high voltage safety procedures, specific vehicle systems, diagnostic procedures, and emergency response. Certification requires periodic renewal to ensure technicians remain current with evolving technology.

Working knowledge of motor theory, power electronics, control systems, and electromagnetic principles is essential for effective diagnosis. The interaction between battery, motor controller, motor, and vehicle control systems is complex. Diagnosing problems requires understanding how these systems work together and where failures can occur.

Why DIY Service Is Dangerous and Impractical

Multiple factors make traction motor service unsuitable for DIY work, even for experienced home mechanics.

The electrocution risk cannot be overstated. Unlike the 12V electrical systems in traditional vehicles, which present minimal shock hazard, the 200-800V in traction motor systems can kill instantly. There is no safe way for untrained persons to work on energized high voltage systems. Even with the system de-energized, capacitors can store lethal energy for hours. Testing to verify safe conditions requires equipment and knowledge most DIYers lack.

Arc flash presents another severe hazard. If tools or conductors create unintended connections in the high voltage system, the resulting arc can reach temperatures exceeding 35,000°F—four times the surface temperature of the sun. This instantaneous heat can vaporize metal tools, ignite clothing, and cause severe burns. The blast force from arc flash can throw personnel across a room. Proper PPE provides limited protection; prevention through correct procedures is essential.

The financial risk of improper service is substantial. Incorrect procedures can damage the motor (replacement cost $3,000-$8,000), motor controller (replacement cost $2,000-$5,000), battery system (replacement cost $5,000-$15,000), or multiple components simultaneously. A single mistake can create damage exceeding the vehicle’s value.

Modern vehicles integrate traction motors tightly with multiple control systems. The motor controller communicates with the battery management system, vehicle dynamics control, traction control, thermal management system, and other computers through high-speed networks. Diagnostic procedures require the ability to monitor and interpret these communications. Parameter adjustments require special procedures to ensure the calibrations remain coordinated across systems.

Warranty implications are serious. Virtually all manufacturers void warranties if unauthorized persons perform high voltage system service. The cost savings from DIY work disappears instantly when a subsequent failure isn’t covered by warranty due to previous unauthorized service.

When to Consult Professional Technicians

Professional evaluation should occur in these situations:

Any reduction in power or performance requires diagnosis to determine whether the problem originates in the motor, controller, battery, or other systems. Seemingly minor performance reductions can indicate developing problems that will worsen if not addressed.

Unusual noises or vibrations from the motor or drivetrain demand immediate professional attention. Bearing problems, rotor imbalance, or internal damage can progress rapidly from minor symptoms to catastrophic failure.

Overheating warnings or coolant leaks indicate problems with the thermal management system. Operating with inadequate cooling causes accelerated wear and risks permanent motor damage.

After collision or impact damage, the entire high voltage system should be professionally inspected. Impacts can damage cables, connectors, sensors, or housings in ways that create safety hazards or reliability problems.

During routine maintenance intervals specified by the manufacturer, typically every 50,000-100,000 miles, professional service should include coolant system service, insulation resistance testing, vibration analysis, and comprehensive diagnostic testing.

Before high voltage system work of any kind, including seemingly unrelated repairs that require disconnecting the high voltage battery or accessing areas near high voltage components, professional involvement ensures proper safety procedures.

The complexity and hazards associated with traction motor systems mean that professional service isn’t just recommended—it’s essential for safety, reliability, and maintaining the significant investment represented by an electric or hybrid vehicle. The educational value of understanding how these systems work is substantial, enabling informed discussions with service technicians and better appreciation of the sophisticated technology. However, understanding how something works differs fundamentally from possessing the training, equipment, and certification to service it safely and effectively.

For questions about traction motor operation, symptoms, or service recommendations, consult certified technicians at dealerships or independent repair facilities with hybrid/EV certification. These professionals have the knowledge, equipment, and training to diagnose and repair these complex systems safely while maintaining the vehicle’s performance and protecting your investment.

Related Topics:

- How Car Batteries Work – Understanding conventional battery systems

- How Starter Motors Work – Comparison with conventional starting systems

- How EV Charging Ports Work – The charging interface for electric vehicles

This article is for educational purposes only. Traction motors operate at dangerous high voltages. Never attempt service on high voltage systems. Only certified technicians should perform diagnosis and repair of traction motor systems.