Modern vehicles are rolling computer networks. Your car contains 70 to 100+ Electronic Control Units (ECUs) constantly exchanging thousands of messages per second. These digital conversations coordinate everything from engine timing to emergency braking, transforming mechanical systems into integrated smart platforms.

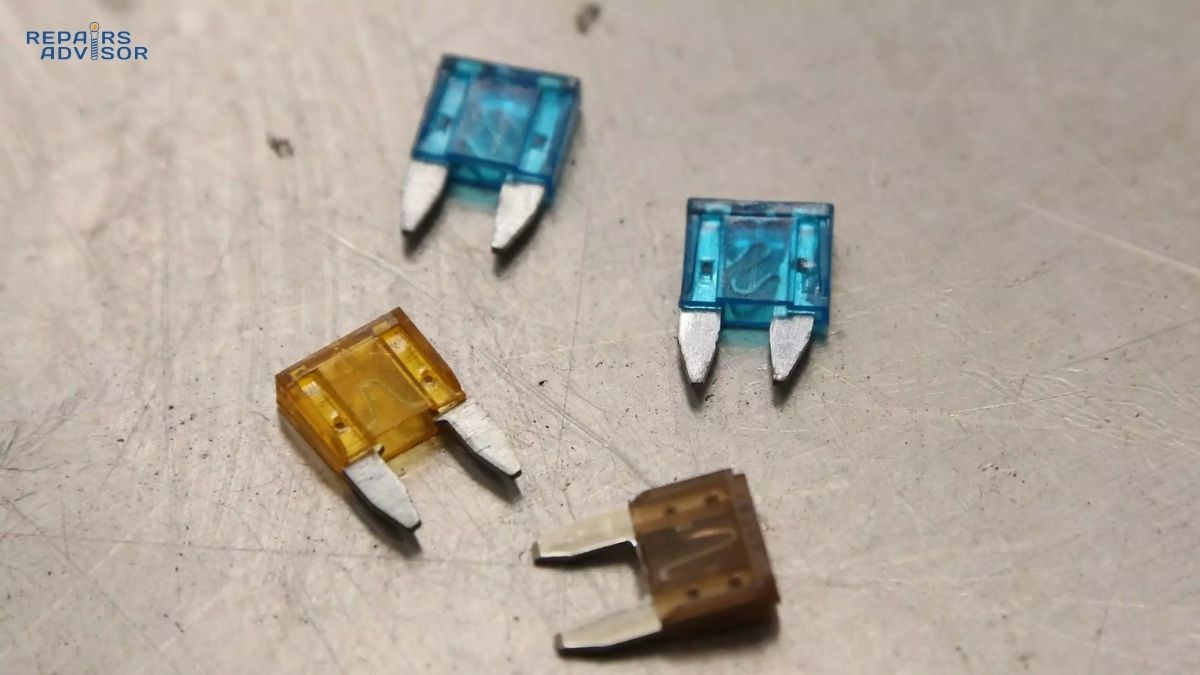

Vehicle networks didn’t always exist. Before the mid-1980s, every sensor and actuator required dedicated wiring. A luxury vehicle could contain over 2,000 individual wires, creating massive harnesses that were heavy, expensive, and prone to failure. The introduction of network communication revolutionized automotive design, reducing wiring weight by up to 50% while enabling features that were previously impossible.

Today’s vehicles rely on four primary network types, each optimized for specific tasks. CAN (Controller Area Network) handles safety-critical functions like braking and steering. LIN (Local Interconnect Network) manages comfort features like power windows and mirrors. FlexRay enables advanced chassis control with microsecond precision. Automotive Ethernet delivers the bandwidth needed for cameras, radar, and autonomous driving systems. Understanding how engine management systems and other control systems communicate through these networks helps you diagnose issues and appreciate the engineering underneath your vehicle’s hood.

The journey from simple electrical circuits to sophisticated network architectures represents one of automotive engineering’s most significant advances. Modern wiring harnesses and grounding systems have evolved to accommodate these digital communication highways that make advanced vehicle features possible.

Why Vehicle Networks Are Critical: Beyond Simple Communication

The Evolution from Point-to-Point to Network Architecture

Pre-1980s automotive electrical systems used point-to-point wiring. Each switch connected directly to its load through dedicated wires. A power window system required separate wires for up, down, one-touch, and anti-pinch protection. Multiply this across four doors, and the wiring complexity became staggering.

Consider a 1980 Mercedes-Benz S-Class with all available options. The wiring harness weighed over 50 kilograms and contained more than 2,000 individual wires. Installing this harness required dozens of hours of labor. Adding new features meant physically running additional wires through the vehicle, which limited design flexibility and increased warranty costs when connections failed.

The breakthrough came in 1986 when Bosch introduced the CAN protocol at the Society of Automotive Engineers Congress in Detroit. This message-based communication system allowed multiple devices to share a single two-wire bus. Instead of 20 wires connecting various sensors to the engine control unit, a single twisted pair could carry all the data.

Mercedes-Benz became the first manufacturer to implement this technology in production. The 1991 W140 S-Class featured a CAN-based multiplex wiring system that reduced harness weight by 40% while adding more electronic features than any previous Mercedes model. This set the template for modern vehicle architecture, where networks form the backbone of all electronic systems.

The benefits extended beyond weight savings. Network-based architectures improved reliability by reducing connection points. They enabled sophisticated diagnostics through standardized communication protocols. Most importantly, they made it economically feasible to add advanced features that require coordination between multiple sensors and actuators.

Mission-Critical Functions Dependent on Vehicle Networks

Vehicle networks aren’t just convenience features—they’re essential for safety and performance. Consider anti-lock braking, which requires continuous monitoring of four wheel speed sensors and precise control of brake pressure at each wheel. The ABS module must detect a locking wheel and modulate brake pressure within 10 milliseconds to prevent loss of control.

This level of coordination is only possible through high-speed network communication. ESC and brake-by-wire systems continuously receive wheel speed data over the chassis CAN bus, compare speeds to detect locking conditions, command the hydraulic modulator valves, and broadcast intervention status to other systems. Electronic Stability Control adds another layer, coordinating ABS intervention with engine torque reduction and individual wheel braking to maintain vehicle stability.

Powertrain systems demonstrate equally critical network dependencies. Your engine’s throttle body no longer connects directly to the accelerator pedal through a cable. Instead, the pedal position sensor transmits your input over CAN to the engine control unit, which calculates optimal throttle opening based on dozens of parameters including engine speed, vehicle speed, transmission gear, and catalyst temperature. This electronic throttle control enables features like traction control, cruise control, and automated emergency braking that would be impossible with mechanical linkages.

Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) push network requirements even further. Adaptive cruise control synthesizes data from radar sensors, cameras, and GPS to maintain safe following distances. Automatic emergency braking must process camera and radar inputs, determine collision risk, and apply maximum braking force within 100 milliseconds. These systems generate so much data that traditional CAN networks can’t handle the bandwidth, driving adoption of Automotive Ethernet.

Even routine diagnostics depend on vehicle networks. When you connect a scan tool to your vehicle’s OBD-II port, you’re accessing the network that connects all control modules. The scan tool sends standardized requests over CAN, and each module responds with diagnostic trouble codes, live data streams, and system status. Understanding OBD codes and reading procedures provides essential insight into how networks enable modern vehicle diagnostics.

Network Architecture Complexity Hierarchy

Modern vehicles implement hierarchical network architectures with different protocols optimized for specific tasks. Understanding this hierarchy is essential for effective diagnostics and repair.

Tier 1 networks handle safety-critical functions requiring guaranteed delivery and minimal latency. The powertrain CAN bus typically operates at 500 kbps or 1 Mbps, carrying messages from engine and transmission controllers. The chassis CAN bus runs at similar speeds, connecting ABS, steering control, and suspension systems. These networks use high-priority message identifiers and strict timing requirements to ensure safety-critical data always gets through.

Tier 2 networks manage comfort and convenience features where occasional message loss is acceptable. Body electronics typically use lower-speed CAN (125-250 kbps) or LIN bus (1-20 kbps). Door modules, climate control, and interior lighting connect through these networks. The reduced speed lowers costs while providing adequate bandwidth for non-critical functions.

Tier 3 networks deliver high bandwidth for data-intensive applications. Automotive Ethernet running at 100 Mbps to 1 Gbps connects camera systems, radar sensors, and advanced processing units. These networks support ADAS features that require real-time processing of massive data streams.

Gateway modules serve as translators between these different network domains. A central gateway ECU might connect five separate CAN buses, two LIN clusters, and an Ethernet backbone. The gateway forwards relevant messages between networks while filtering unnecessary data. It also provides security by preventing unauthorized access from lower-security domains (like infotainment) to safety-critical networks (like braking and steering).

This architecture allows engineers to optimize each network for its specific task. Safety-critical systems get robust, proven CAN technology. Cost-sensitive applications use simple LIN. Bandwidth-hungry ADAS features leverage Ethernet. Understanding these architectural choices helps diagnose network-related problems by identifying which domain a particular system belongs to.

CAN Bus: The Backbone of Automotive Communication

Physical Layer Architecture

CAN (Controller Area Network) uses twisted-pair differential signaling to achieve noise immunity in the harsh automotive environment. Two wires—CAN High (CANH) and CAN Low (CANL)—carry complementary signals. When one wire goes high, the other goes low by an equal amount. This differential signaling cancels out electromagnetic interference that affects both wires equally.

The physical implementation is straightforward but critical. CANH and CANL must be twisted together (typically 1-2 twists per inch) to ensure equal exposure to external noise. Proper twisting maintains the differential signal’s integrity and improves electromagnetic compatibility. The twisted pair runs along the vehicle’s length, usually under the dashboard or through the center tunnel, connecting each ECU through short stub connections.

Voltage levels define the bus state. In the recessive state, both CANH and CANL sit at approximately 2.5 volts (relative to ground). When any node transmits a dominant bit, it drives CANH to approximately 3.5 volts while pulling CANL to 1.5 volts. The differential voltage (CANH minus CANL) determines the bit state: near zero volts for recessive, approximately 2 volts for dominant.

Termination resistors are essential for signal integrity. A 120-ohm resistor must be placed at each physical end of the bus. These resistors prevent signal reflections that would corrupt data transmission. You can verify proper termination by disconnecting all ECUs and measuring resistance between CANH and CANL—you should read 60 ohms (two 120-ohm resistors in parallel).

The relationship between bus speed and cable length is inverse. At maximum speed (1 Mbps), the bus can extend only about 40 meters. This limitation comes from signal propagation delay and the need for all nodes to synchronize bit timing. Lower speeds permit longer cables: 500 kbps allows 100 meters, 250 kbps permits 200 meters, and 125 kbps supports up to 500 meters. Most vehicles use 250-500 kbps for chassis and body systems, reserving 1 Mbps for powertrain where cable lengths are short.

Stub connections from the main bus to each ECU must be kept very short—ideally under 30 centimeters. Longer stubs create impedance mismatches that generate reflections and reduce bus reliability. Professional automotive wiring harnesses minimize stub lengths through careful physical routing and connector placement.

Data Link Layer Protocol

CAN uses a message-oriented broadcast system fundamentally different from traditional networking. Instead of sending messages to specific destination addresses, CAN nodes broadcast messages identified by content. Any node can transmit a message with a specific identifier, and all nodes receive that message. Each node decides independently whether to process or ignore received messages based on their identifiers.

This broadcast approach eliminates the need for routing tables or address management. When the accelerator pedal ECU wants to inform the engine controller about throttle position, it broadcasts a message with identifier 0x201 (hexadecimal). The engine ECU knows to process messages with that identifier, while other ECUs ignore them. This publish-subscribe model simplifies network configuration and makes adding nodes straightforward.

Message identifiers serve dual purposes. They identify the message content (what data the frame carries) and determine transmission priority. Lower identifier values have higher priority. Critical messages like brake intervention requests use low identifiers (high priority), while routine status updates use high identifiers (low priority). This priority system ensures that safety-critical data always gets through during heavy bus loading.

The CAN 2.0 specification defines two identifier formats. Standard frames (CAN 2.0A) use 11-bit identifiers, supporting 2,048 unique message IDs. Extended frames (CAN 2.0B) use 29-bit identifiers, supporting over 536 million unique IDs. Most automotive applications use standard frames for simplicity, reserving extended frames for diagnostics and special applications.

Non-destructive bitwise arbitration is CAN’s most elegant feature. When multiple nodes try to transmit simultaneously, arbitration resolves conflicts without corrupting any messages. All transmitting nodes start sending their message identifiers bit by bit. If a node transmits a recessive bit (1) but sees a dominant bit (0) on the bus, it immediately stops transmitting and switches to receive mode. The node with the lowest identifier value (highest priority) wins arbitration and continues transmitting without disruption or retransmission delay.

The data field carries the actual payload—anywhere from zero to eight bytes. A typical message might be four bytes: two bytes for a 16-bit sensor reading, one byte for status flags, and one byte for a rolling counter to detect missing messages. The compact 8-byte maximum encourages efficient encoding and reduces bus loading.

CAN Frame Structure Breakdown

Understanding CAN frame structure helps diagnose communication problems and optimize bus loading. Every CAN message follows the same format, though different frame types have slight variations.

The Start of Frame (SOF) consists of a single dominant bit that marks the beginning of a message. This synchronizes all nodes and signals that the bus is transitioning from idle to active. All nodes adjust their internal bit timing based on this edge.

The arbitration field contains the message identifier and determines who gets to use the bus. During this phase, multiple nodes may be transmitting simultaneously. Each node monitors the bus and compares what it’s sending to what appears on the bus. If they differ (the node sent recessive but sees dominant), the node loses arbitration and stops transmitting.

The control field specifies the data length code (DLC), indicating how many bytes of data follow. Valid values range from 0 to 8. Some protocols use DLC values above 8 for special purposes, though the standard limits actual data to eight bytes.

The data field contains the payload—the actual information being transmitted. This could be sensor readings, actuator commands, status flags, or diagnostic data. Efficient message design packs multiple signals into each frame. For example, an engine status message might include coolant temperature, oil pressure, and throttle position in a single 6-byte frame transmitted every 10 milliseconds.

The CRC (Cyclic Redundancy Check) field provides error detection through a 15-bit checksum. The transmitting node calculates this checksum based on the frame contents. Receiving nodes recalculate the CRC and compare it to the transmitted value. Any mismatch indicates bit errors, causing the receiving node to flag an error and request retransmission.

The ACK (Acknowledge) field serves as confirmation that at least one node correctly received the message. The transmitting node sends a recessive bit during the ACK slot. Any node that received the frame correctly overwrites this with a dominant bit, acknowledging successful reception. If the transmitter doesn’t see a dominant ACK bit, it knows the message wasn’t received and will retry.

The End of Frame (EOF) marker consists of seven recessive bits, signaling message completion. After EOF, nodes must wait for a brief intermission period (three recessive bits) before transmitting the next message. This gap allows nodes to process received messages and prepare for the next arbitration cycle.

Error Detection and Fault Tolerance

CAN implements five complementary error detection mechanisms, achieving an undetected error rate below one per billion messages. This reliability is essential for safety-critical applications where corrupted data could cause accidents.

Bit monitoring is the simplest mechanism. Every transmitting node monitors the bus and compares what it sent to what appears on the bus (except during arbitration and ACK, where differences are expected). Any unexpected difference triggers a bit error.

Bit stuffing maintains synchronization and prevents long strings of identical bits. After five consecutive identical bits, the transmitter automatically inserts one opposite bit. Receivers automatically remove these stuffed bits. If a receiver doesn’t see the expected stuffed bit, it flags a stuffing error.

Frame checking verifies that certain fixed-format fields contain the expected values. The CRC delimiter, ACK delimiter, and EOF must all be recessive bits. Any dominant bit in these positions indicates a form error.

CRC checking catches most random bit errors. The 15-bit CRC has a Hamming distance of 6, meaning it can detect all error patterns affecting up to five bits. For typical message lengths, it also detects nearly all error patterns affecting more than five bits.

Acknowledge checking ensures at least one node received the message correctly. If no node sends a dominant ACK bit, the transmitter knows the message didn’t get through and flags an acknowledge error.

When any node detects an error, it immediately transmits an error frame—six consecutive dominant bits that violate the bit stuffing rule. This ensures all nodes detect the error and discard the corrupted message. The transmitter then automatically retries up to 16 times before giving up.

Error confinement prevents faulty nodes from disrupting the network. Each node maintains transmit and receive error counters that increase with errors and decrease with successful transmissions. Based on counter values, nodes operate in three states: error-active (normal, counters below 128), error-passive (degraded, counters 128-255), and bus-off (disconnected, transmit counter exceeds 255). This prevents a permanently faulty node from blocking the entire network.

CAN FD: Enhanced Data Rate Extension

CAN FD (Flexible Data rate) extends classical CAN to support higher bandwidth while maintaining backward compatibility in mixed networks. The “flexible” refers to two key enhancements: faster data transmission and larger payloads.

The fundamental innovation is dual-bitrate operation. Arbitration occurs at the standard CAN rate (typically 500 kbps) to ensure all nodes can participate in bus access. Once a node wins arbitration, it switches to a faster bitrate (up to 8 Mbps) for transmitting the actual data. This approach provides high throughput while preserving CAN’s proven arbitration mechanism.

Payload size increases dramatically from 8 bytes to 64 bytes per frame. This 8x increase reduces protocol overhead for data-intensive applications. Instead of sending eight separate CAN messages with eight bytes each (totaling 368 bits including headers and checksums), a single CAN FD message can carry 64 bytes in approximately 200 bits at high speed—a 4x improvement in effective throughput.

The protocol modifications are minimal but important. CAN FD frames include additional control bits to signal the use of FD format and faster bitrate switching. The CRC algorithm is enhanced to maintain error detection capability for longer messages. These changes require updated CAN controllers in ECUs, but the physical layer remains unchanged—the same twisted-pair wiring works for both classical CAN and CAN FD.

Practical applications include flash programming (reprogramming ECU software through OBD-II), high-resolution diagnostic data logging, and coordination of multiple sensors for ADAS. For even higher bandwidth solutions, see our guide on Automotive Ethernet.

Real-World CAN Bus Applications

CAN bus segmentation separates vehicle functions into logical domains, each operating at speeds optimized for their requirements. This segmentation improves security, simplifies diagnostics, and allows engineers to tune each network independently.

Powertrain CAN (typically 500 kbps – 1 Mbps) connects the engine control module, transmission control module, and related sensors. Every 10 milliseconds, the engine ECU broadcasts status including RPM, throttle position, and coolant temperature. The transmission ECU uses this data to determine optimal shift points. Variable valve timing actuators receive position commands through this network. The high speed ensures rapid response to driver inputs and changing conditions.

Chassis CAN (typically 500 kbps) handles steering, suspension, and braking systems. The ABS module receives wheel speed data every 10 milliseconds and broadcasts brake intervention status. Electronic power steering receives vehicle speed, yaw rate, and driver input data to calculate optimal assist levels. Active suspension systems adjust damping rates based on body acceleration and road inputs.

Body CAN (typically 125-250 kbps) manages comfort and convenience features. Door modules control power windows, mirrors, and locks. The HVAC system coordinates compressor speed, blend door positions, and blower fan based on cabin temperature sensors. Lighting controllers manage interior, exterior, and ambient lighting.

Infotainment CAN (typically 125 kbps) provides a separate network for audio systems, navigation, and telematics. This isolation prevents entertainment system crashes or software updates from affecting vehicle operation. The infotainment network usually connects to other networks through a gateway that carefully filters messages.

Gateway modules interconnect these networks, forwarding necessary messages while maintaining security boundaries. For example, the instrument cluster needs engine RPM from the powertrain CAN to display the tachometer. The gateway subscribes to the RPM message on powertrain CAN and republishes it on the body CAN where the cluster resides.

LIN Bus: Cost-Effective Sub-Network Protocol

Master-Slave Architecture Fundamentals

LIN (Local Interconnect Network) uses deterministic master-slave architecture, a stark contrast to CAN’s multi-master approach. This simplification reduces hardware costs and enables use of basic microcontrollers without specialized communication peripherals.

A single master node controls all bus activity. Only the master can initiate message transmission. It follows a predefined schedule table that specifies exactly which messages transmit at what times. This schedule is embedded in the master’s software during vehicle development and remains fixed during normal operation. The predictable timing guarantees that critical messages always get through, though it sacrifices the flexibility of CAN’s priority-based arbitration.

Slave nodes respond when commanded by the master. A typical LIN cluster contains 4-8 slaves, though the specification allows up to 16. Each slave listens for message headers transmitted by the master. When a slave recognizes its assigned message identifier, it responds with the requested data. Slaves never initiate communication—they wait to be polled by the master.

This architecture perfectly suits applications like door modules. The master (typically the body control module) schedules messages like “left front window position” every 50 milliseconds. When the left front door module sees this message identifier, it responds with the current window position. If the driver presses the window switch, the door module updates its response on the next scheduled poll.

Time-triggered scheduling provides guaranteed latency. Unlike CAN where high bus loading can delay low-priority messages, LIN guarantees every message transmits at its scheduled time. For window control, this means the window always responds within a predictable time frame, creating consistent user experience. The master-slave architecture also simplifies diagnostics and integrates well with smart power distribution systems.

Physical Layer Simplification

LIN achieves dramatic cost reduction through physical layer simplification. Instead of CAN’s specialized transceivers and twisted-pair requirements, LIN uses simple UART (Universal Asynchronous Receiver-Transmitter) hardware present in most microcontrollers.

Single-wire communication is LIN’s defining physical characteristic. The bus consists of one signal wire (LIN) plus ground and 12V battery power—just three wires total. The master ECU includes a 1-kilohm pull-up resistor connecting the LIN wire to battery voltage. Each slave ECU contains a 30-kilohm pull-up resistor. This creates a wired-AND configuration where any node can pull the bus low (dominant state), but the bus returns high (recessive state) when no node drives it.

The UART-based approach means simple microcontrollers can implement LIN without specialized hardware. The microcontroller’s standard UART transmitter/receiver handles bit-level communication. Basic transistor circuits drive the bus low for transmission and sense bus voltage for reception. This implementation costs just a few dollars per node compared to $10-20 for CAN transceivers.

Speed limitations are LIN’s main tradeoff. The protocol specifies 1-20 kbps, with 9.6 and 19.2 kbps being most common. These speeds are 50-500 times slower than CAN. However, for applications like power windows and mirror adjustment, this bandwidth is completely adequate. A window position update requires only 4 bytes transmitted every 50 milliseconds—roughly 640 bits per second, leaving plenty of bandwidth for other functions.

Cable length is limited to approximately 40 meters, similar to high-speed CAN. This constraint rarely matters in practice since LIN applications like door modules and seat controls are physically close to their master controller. The single-wire approach means lower EMI immunity compared to CAN’s differential signaling, so LIN wiring requires more careful routing away from ignition systems and other noise sources.

LIN Message Frame Format

LIN frames consist of two parts: a header transmitted by the master and a response transmitted by either a slave or the master itself. This split structure enables the deterministic master-slave communication model.

The header contains three fields. First, the break field provides synchronization—a dominant level lasting at least 13 bit times (typically 13-20 bit times). This violates normal UART framing and unmistakably signals the start of a new message header. All slave nodes detect the break and prepare to receive the subsequent sync and ID fields.

Second, the sync field consists of the byte value 0x55 (binary 01010101). This alternating bit pattern allows slaves to measure bit timing and adjust their UART baud rates. Since LIN slaves use low-cost RC oscillators instead of crystals, their base frequencies can vary by several percent. The sync field provides automatic baud rate adaptation, ensuring slaves correctly interpret subsequent bits despite oscillator variations.

Third, the protected identifier contains a 6-bit message identifier plus 2-bit parity. The 6-bit ID supports 64 unique messages. IDs 0-59 carry normal signal data. ID 60 and 61 are reserved for diagnostic requests and responses. ID 62 allows user-defined extensions. ID 63 is reserved for future protocol enhancements.

The response contains data bytes and a checksum. Data length is specified in the LIN Description File (LDF) during network design—typically 2, 4, or 8 bytes depending on the message. Each byte transmits using standard UART framing. The checksum provides error detection for the entire frame.

Understanding frame structure helps diagnose LIN communication issues. A scope trace showing proper break, sync, and ID fields but missing response indicates a slave problem. Missing ACK or checksum errors suggest electrical issues on the bus.

Typical LIN Applications in Modern Vehicles

LIN excels at applications requiring simple sensors, actuators, and switches where CAN’s capability exceeds requirements and costs must be minimized. Door modules represent the canonical LIN application.

Door modules aggregate switches and actuators in each door. The module monitors window switches (up/down/auto), mirror adjustment joystick, door lock button, and power fold mirror button. It controls window motors, mirror motors, mirror heaters, and door lock actuators. All this functionality communicates to the body control module through a single three-wire LIN connection. Before LIN, each switch and actuator required dedicated wiring through the door jamb—a complex, expensive harness prone to fatigue failures.

Seat control presents similar advantages. Modern power seats have 8-12 motors controlling lumbar support, side bolsters, cushion length, height, tilt, and fore-aft position. Memory functions store positions for multiple drivers. Heating and cooling elements require PWM control. Using LIN, all these actuators and position sensors connect to a seat module that communicates with the body controller over three wires.

Climate control uses LIN to connect blend door actuators, fresh air doors, and recirculation flaps to the HVAC controller. Instead of running separate wires to each actuator behind the dashboard, LIN enables star or daisy-chain topologies with short local connections, coordinating with the broader climate system.

Lighting systems benefit from LIN’s low cost per node. Exterior lighting uses LIN to communicate LED driver status, bulb-out detection, and automatic leveling adjustment. Interior lighting systems employ LIN for ambient lighting zones, reading lights, and puddle lamps. Each lighting control module reports bulb status and fault codes through LIN to the body controller.

Steering wheel controls consolidate cruise control, audio controls, phone buttons, and voice activation into a steering wheel module connected via LIN. This approach greatly simplifies the wiring through the steering column while enabling additional buttons without significant cost increases.

LIN-to-CAN Gateway Integration

LIN clusters don’t operate in isolation—they integrate into the broader vehicle network through gateway modules that bridge LIN and CAN. This hierarchical architecture optimizes the entire system cost and performance.

Consider a steering wheel module connected via LIN to a steering column control module (the LIN master). When you press the volume-up button, this sequence occurs:

- Steering wheel module detects button press and updates its state variable

- On the next scheduled poll (typically every 20 milliseconds), the steering wheel module responds with its button status

- The steering column control module receives the LIN response and recognizes the volume-up command

- The control module translates this into a CAN message and transmits it on the body CAN bus

- The gateway module receives the message on body CAN and forwards it to the infotainment CAN bus

- The radio receives the message and increases volume

This translation happens seamlessly from the user’s perspective. The multi-network architecture allows using low-cost LIN for the button matrix while the radio continues using CAN for higher-bandwidth functions.

Gateway functions include more than simple translation. The gateway filters messages, forwarding only necessary data between networks. It also implements security policies, preventing infotainment systems from sending commands to safety-critical networks. During diagnostics, the gateway routes scan tool requests from the OBD-II port to the appropriate LIN cluster, enabling technicians to read fault codes and configure LIN slaves.

FlexRay: High-Speed Deterministic Communication

Time-Triggered Architecture Fundamentals

FlexRay was designed for x-by-wire applications where mechanical linkages are replaced with electronic control—systems like steer-by-wire, brake-by-wire, and active suspension that demand guaranteed timing and fault tolerance. The protocol achieves this through time-triggered architecture fundamentally different from CAN’s event-driven model.

Every FlexRay node maintains a synchronized global time base. During network startup, nodes exchange synchronization messages and adjust their local clocks to achieve agreement within microseconds. This global time serves as the reference for all communication. Unlike CAN where nodes transmit based on events, FlexRay nodes transmit at predefined times in the communication cycle.

The communication cycle is the fundamental unit of FlexRay operation. A typical cycle lasts 5 milliseconds and repeats continuously. The cycle divides into several segments:

The static segment uses Time Division Multiple Access (TDMA). Each node gets an exclusive time slot to transmit. This guarantees bandwidth—no matter how busy the network, each node gets its reserved slot. The static segment carries time-critical data like steering angle, brake pressure commands, and suspension control. Messages here have guaranteed maximum latency down to the microsecond.

The dynamic segment handles less-critical data using prioritized transmission similar to CAN. This segment divides into minislots. Nodes with data to send wait for their assigned minislot, then transmit if they have pending messages. The dynamic segment carries diagnostic data, configuration commands, and other non-time-critical information.

The symbol window accommodates special signals for network management. Wakeup symbols rouse sleeping nodes. Collision avoidance symbols help handle startup conditions.

The network idle time provides a gap between cycles for processing. Nodes complete message reception, update application variables, and prepare for the next cycle during this idle period.

This deterministic timing enables applications impossible with event-driven protocols. Consider active suspension: each wheel’s damper must adjust every 5 milliseconds based on inputs from accelerometers, ride height sensors, and steering angle. FlexRay guarantees all sensor data arrives and actuator commands go out within the 5-millisecond cycle. Even under heavy bus loading, timing never degrades.

Dual-Channel Redundancy

FlexRay’s most distinctive feature is optional dual-channel operation. The protocol defines two independent physical channels—Channel A and Channel B—each capable of 10 Mbps. Nodes can connect to one channel (cheaper) or both channels (more reliable).

Redundancy mode transmits identical data on both channels simultaneously. If one channel fails due to a wire break or connector corrosion, communication continues on the surviving channel. The receiving node monitors both channels and uses whichever has valid data. This redundancy is essential for safety-critical applications. A brake-by-wire system can’t tolerate any single-point failures in communication, so dual-channel redundancy provides the required fault tolerance.

Dual-channel operation sends different data on each channel, effectively doubling bandwidth to 20 Mbps. Channel A might carry sensor inputs while Channel B carries actuator commands. This mode suits bandwidth-intensive applications where redundancy is less critical than throughput.

Single-channel mode uses only one channel to reduce costs. Less-critical nodes often implement single-channel connection to save on transceiver costs while still participating in the network.

The physical implementation uses separate twisted pairs for each channel. Each channel requires 120-ohm termination resistors at both ends, similar to CAN. The independence of channels means a short circuit on Channel A doesn’t affect Channel B—they’re electrically isolated.

Differential signaling on each channel provides noise immunity. BusPower (BP) and BusMinus (BM) carry complementary signals similar to CAN’s CANH/CANL. The voltage levels differ slightly, but the principle is the same. This differential signaling allows FlexRay to achieve 10 Mbps while maintaining automotive EMI compliance.

Safety-Critical FlexRay Applications

FlexRay found primary application in advanced chassis control systems requiring both high speed and guaranteed timing. These systems coordinate multiple actuators with tight latency requirements that CAN couldn’t meet.

Active suspension systems represent FlexRay’s sweet spot. Each wheel has independently-controllable dampers that adjust every few milliseconds based on body accelerations, road input, and driver actions. The suspension ECU needs synchronized data from four wheel position sensors, six accelerometers (body yaw, pitch, roll), steering angle, brake pressure, and throttle position. Processing this data and commanding four damper actuators requires both high bandwidth and guaranteed latency.

BMW’s first production FlexRay implementation in the 2006 X5 (E70) controlled the Dynamic Drive active anti-roll system. FlexRay coordinated signals from multiple sensors to control hydraulic actuators that reduced body roll during cornering. The system demonstrated FlexRay’s capability but also highlighted cost challenges.

Integrated chassis control became FlexRay’s primary use case. These systems coordinate braking, steering, and throttle for enhanced stability beyond what traditional ESC provides. Automatic emergency braking and similar adaptive cruise control features benefit from FlexRay’s guaranteed timing, though newer systems often use CAN FD or Automotive Ethernet instead.

Despite technical advantages, FlexRay adoption peaked around 2010-2015 and has since declined. Most manufacturers chose to skip FlexRay entirely, waiting for Automotive Ethernet to mature. The extensive configuration requirements, limited tool availability, and high transceiver costs made FlexRay uneconomical except for the most demanding applications.

FlexRay vs. CAN Comparison

Comparing FlexRay to CAN illuminates their different design philosophies and appropriate applications.

Speed: FlexRay delivers 10 Mbps per channel, 10x faster than Classical CAN (1 Mbps) and 25% faster than CAN FD (8 Mbps). For bandwidth-intensive applications, FlexRay provides significant advantages.

Determinism: FlexRay’s time-triggered scheduling guarantees maximum latency for every message. In the static segment, you can calculate exactly when every message will arrive—±1 microsecond. CAN is non-deterministic; high bus loading can delay low-priority messages by milliseconds.

Configuration complexity: CAN is essentially plug-and-play. Assign message IDs, set the baud rate, connect nodes—done. FlexRay requires extensive planning: calculate communication cycle duration, assign static slots, configure dynamic segment, tune time synchronization parameters. Specialized tools costing tens of thousands of dollars are necessary.

Hardware cost: FlexRay transceivers cost 3-5x more than CAN transceivers. Dual-channel implementations double this again. For cost-sensitive applications, these hardware costs are prohibitive.

Fault tolerance: Dual-channel FlexRay provides superior redundancy. CAN lacks physical redundancy but compensates with aggressive error detection and automatic retry.

Bandwidth efficiency: FlexRay’s static segment wastes bandwidth if nodes don’t have data to send—the slot goes unused. CAN only transmits when nodes have data, making more efficient use of available bandwidth.

The practical result: FlexRay suits high-end chassis control systems requiring deterministic communication and fault tolerance. CAN remains dominant for powertrain, body electronics, and infotainment. Most vehicles with advanced chassis control now use CAN FD or Automotive Ethernet instead of FlexRay.

Automotive Ethernet: High-Bandwidth Future

100BASE-T1 Physical Layer

Automotive Ethernet adapts standard Ethernet technology for the harsh vehicle environment while reducing cost and weight. The key innovation is 100BASE-T1 (IEEE 802.3bw), which delivers 100 Mbps full-duplex over a single unshielded twisted pair.

Standard Ethernet (100BASE-TX) requires two twisted pairs—one for transmit, one for receive. Automotive Ethernet uses one pair for both directions simultaneously through full-duplex signaling. This halves the copper weight and simplifies connector design. The single-pair approach combined with unshielded cable achieves 50% weight reduction compared to standard Ethernet cables.

PAM3 encoding (3-level Pulse Amplitude Modulation) enables full-duplex communication on one pair. Instead of simple high/low voltage levels, PAM3 uses three discrete levels: +1V, 0V, -1V. This allows transmitting more information per symbol while keeping the signaling frequency moderate. The encoding scheme uses 4B3B (4 bits to 3 bits) followed by 3B2T (3 bits to 2 ternary symbols) conversion.

The result meets CISPR 25 Class 5 radiated emissions limits—the strictest automotive EMI standard. Standard Ethernet cables act like antennas broadcasting radio interference. Automotive Ethernet’s twisted-pair topology and PAM3 encoding minimize emissions while maintaining noise immunity. This compliance is essential for automotive use where radio reception quality directly affects customer satisfaction.

Cable specifications balance cost and performance. Typical 100BASE-T1 cables use 24 AWG solid conductors with 15-25 meters maximum length. The impedance is 100 ohms ±10%, requiring proper termination in the PHY transceivers. Unlike CAN’s resistor terminators, Ethernet termination is integrated into the PHY chip, simplifying installation.

The physical layer enables Ethernet’s key advantages: backwards compatibility with decades of Ethernet development, availability of low-cost switches and PHYs due to high production volumes, and support for standard Internet Protocol networking.

1000BASE-T1 Gigabit Ethernet

As bandwidth demands increase, 1000BASE-T1 (IEEE 802.3bp) delivers 1 Gbps over a single twisted pair—ten times faster than 100BASE-T1. This speed is essential for camera-intensive ADAS systems where each camera can generate 100-300 Mbps.

The physical layer uses PAM3 encoding at 333 MHz—three times faster than 100BASE-T1. This higher frequency necessitates better cables. While 100BASE-T1 works reliably with unshielded cable, 1000BASE-T1 typically requires shielded twisted pair (STP) to meet CISPR 25 emissions limits. The shield adds weight and cost but is necessary at gigabit speeds.

Cable length is more restricted at gigabit speeds—typically 15 meters maximum versus 25 meters for 100BASE-T1. This limitation comes from signal attenuation and timing constraints. For most vehicle applications, 15 meters suffices. Cameras and sensors connect to local zonal controllers within 5-10 meters, while the zonal controllers interconnect through 10-15 meter trunk cables to the central vehicle computer.

Use cases differ between 100BASE-T1 and 1000BASE-T1. Hundred-megabit Ethernet suits single-camera applications, infotainment systems, gateway modules, and diagnostic ports. Gigabit Ethernet handles multi-camera sensor fusion, lidar point clouds, high-resolution radar, zonal backbone trunks, and centralized vehicle computing. Our guides on automotive cameras, radar sensors, and lidar technology explore these bandwidth requirements in detail.

Ethernet Protocol Stack in Automotive

Automotive Ethernet uses standard Ethernet frames and Internet Protocol, providing full compatibility with decades of networking technology. This standardization is a major advantage over proprietary automotive protocols like CAN.

The physical layer (100BASE-T1 or 1000BASE-T1) handles electrical signaling. The PHY transceiver converts digital data from the MAC layer into electrical signals on the twisted pair and vice versa.

The data link layer implements standard Ethernet MAC (Media Access Control). Each node has a unique 48-bit MAC address. Ethernet frames contain source and destination MAC addresses, length/type field, payload (46-1500 bytes), and frame check sequence for error detection.

The network layer typically runs IPv4 or IPv6. This enables standard IP addressing and routing. A vehicle’s Ethernet network might use private IP addresses with the gateway module performing Network Address Translation (NAT) to external networks.

The transport layer uses TCP for reliable delivery or UDP for real-time streams. Camera video typically uses UDP because retransmitting dropped frames isn’t useful. Diagnostic commands use TCP to ensure reliable delivery.

The application layer implements automotive-specific protocols on top of standard Ethernet/IP. SOME/IP (Scalable service-Oriented MiddlewarE over IP) provides service-oriented architecture for automotive applications. DDS (Data Distribution Service) enables publish-subscribe data flow.

This layered architecture means automotive engineers can leverage standard Ethernet tools. A Wireshark packet capture works on automotive Ethernet just like office networks. However, standard Ethernet lacks the determinism required for safety-critical applications. Time-Sensitive Networking extensions solve this problem.

Time-Sensitive Networking (TSN)

TSN (Time-Sensitive Networking) is a collection of IEEE 802.1 standards that add deterministic timing to Ethernet. These extensions enable Ethernet to meet automotive real-time requirements while maintaining standard Ethernet compatibility.

IEEE 802.1AS (Time synchronization) provides the foundation. All nodes synchronize their clocks using the generalized Precision Time Protocol (gPTP). This achieves nanosecond-level time synchronization across the network. With synchronized clocks, nodes can coordinate time-sensitive operations precisely.

IEEE 802.1Qbv (Time-aware shaping) implements time-triggered scheduling similar to FlexRay. The network defines time gates that open and close on a schedule. High-priority time-critical traffic gets reserved gates that guarantee transmission timing. Lower-priority traffic uses remaining bandwidth.

IEEE 802.1Qbu (Frame preemption) allows interrupting low-priority frames to transmit high-priority frames immediately. If a large low-priority frame is being transmitted when a critical brake command arrives, the switch can pause the large frame, transmit the brake command, then resume the interrupted frame.

IEEE 802.1CB (Frame replication and elimination) provides redundancy. Critical frames transmit over multiple paths. The receiving node accepts the first copy and discards duplicates. If one path fails, the redundant path ensures delivery.

Together, these extensions enable Ethernet to support safety-critical automotive applications. TSN-capable switches can guarantee message delivery with microsecond precision while maintaining backwards compatibility with standard Ethernet.

ADAS and Infotainment Applications

Automotive Ethernet’s bandwidth enables applications impossible with CAN or LIN. The most demanding applications are camera-based ADAS systems that require transmitting compressed video streams.

Camera systems generate tremendous data volume. A 720p camera at 30 frames per second produces approximately 60 Mbps after H.264 compression. A 1080p camera requires 100 Mbps. For 4K resolution, expect 200+ Mbps per camera. Modern vehicles with 360-degree surround view use 4-6 cameras, totaling 400-600 Mbps. These bandwidth requirements explain the push toward gigabit Ethernet.

Infotainment backbones were among the first Ethernet adopters. A modern infotainment system includes head unit, amplifier, multiple displays, navigation processor, and telematics module. These devices exchange audio streams, video, navigation data, and control commands. Ethernet provides adequate bandwidth while enabling standard IP networking for cloud connectivity.

Over-the-air (OTA) updates become practical with Ethernet bandwidth. Updating ECU software over CAN requires hours because of bandwidth limitations. Ethernet reduces flash programming time from hours to minutes. A 50-megabyte ECU update that takes 4 hours over 500 kbps CAN completes in 4 minutes over 100 Mbps Ethernet.

Zonal Architecture Transition

Automotive network architecture is undergoing fundamental restructuring from domain-based to zonal-based design. This transition is enabled by Ethernet bandwidth and motivated by wiring cost reduction.

Traditional domain architecture organizes ECUs by function. All powertrain components connect to powertrain CAN. All body electronics connect to body CAN. A typical mid-range vehicle contains 50-80 ECUs distributed throughout the vehicle. This creates complex wiring harnesses with cables running the full vehicle length.

Zonal architecture organizes around physical location rather than function. The vehicle divides into 5-8 zones. Each zone contains a zonal controller that manages all devices in that zone regardless of function. Door modules, seat controls, exterior lighting, and ADAS sensors in the left-front zone all connect to the left-front zonal controller.

The zonal controllers interconnect via high-speed Ethernet backbone trunks to a central vehicle computer. This computer runs the software for all vehicle functions, using the zonal controllers as remote input/output devices.

Wiring benefits are substantial. Instead of routing separate harnesses for body CAN, powertrain CAN, and chassis CAN through the vehicle, a single Ethernet trunk connects each zone to the central computer. This reduces total harness length by 30-50% and weight by similar amounts.

Software-defined vehicle becomes practical with zonal architecture. All vehicle control software runs on the central computer, which can be updated via OTA. Adding new features, fixing bugs, or enabling paid subscription features requires only software updates—no hardware changes.

Gateway Modules and Network Integration

Multi-Network Gateway Functions

Gateway modules serve as the central nervous system of vehicle networks, interconnecting different protocols and security domains. Understanding gateway operation is essential for diagnosing communication faults that affect multiple systems.

Protocol translation is the gateway’s primary function. CAN messages translate to LIN commands, Ethernet packets, or FlexRay frames as needed. When you adjust climate temperature on the dashboard touchscreen (connected via Ethernet), the gateway translates this into LIN commands for the HVAC blend door actuators.

Message routing implements selective forwarding. Not every message needs distribution to every network. The gateway maintains routing tables specifying which messages forward between networks. A wheel speed sensor message originating on the chassis CAN forwards to powertrain CAN (engine needs this data) but not to infotainment Ethernet (no need).

Security firewall functionality prevents unauthorized access between network domains. The infotainment system can read vehicle speed for navigation but can’t send engine commands. Gateway modules enforce these policies through message filtering and authentication.

Diagnostics hub consolidation makes the gateway the primary access point for scan tools. The OBD-II port typically connects directly to the gateway module, which routes diagnostic requests to appropriate ECUs across all networks. Understanding OBD codes and diagnostic procedures reveals how this network integration enables comprehensive vehicle diagnostics.

Wake-up management coordinates network power states. Most vehicle networks sleep when the ignition is off to conserve battery. The gateway orchestrates wake-up cascades, ensuring networks power on in the correct sequence.

Central Gateway Architecture

Modern vehicles implement centralized gateway architecture where a single gateway ECU interconnects all network domains. Typical network domains include:

Powertrain domain CAN (500 kbps – 1 Mbps) connects engine, transmission, and related sensors. Chassis domain CAN (500 kbps) links ABS, ESC, steering control, and suspension systems. Body/comfort domain CAN (125-250 kbps) manages lighting, HVAC, power windows, locks. Infotainment Ethernet (100 Mbps) connects head unit, amplifier, displays, and telematics. ADAS Ethernet (100 Mbps – 1 Gbps) links cameras, radar, lidar, and ADAS processing units.

Gateway ECU location is typically central—under the dashboard, in the center console area, or behind the glove box. This position minimizes cable lengths to the various network hubs.

Message Filtering and Load Management

Gateway modules must carefully manage message flow to prevent bus overload while ensuring critical data reaches its destination.

Bandwidth optimization starts with routing table configuration. Engineers determine during vehicle development which messages must cross network boundaries. For example, engine RPM broadcasts on powertrain CAN every 10 milliseconds. The gateway forwards this to body CAN (instrument cluster needs it) but not to comfort CAN or infotainment Ethernet (unnecessary).

Wake-up coordination prevents power drain. When a wake-up event occurs (door handle pulled), the gateway determines which networks need activation. Opening the driver’s door wakes body CAN and left-front LIN but doesn’t wake powertrain CAN or ADAS Ethernet.

Understanding gateway operation helps diagnose network communication issues. A U0001 code (High Speed CAN Communication Bus fault) might indicate gateway failure, CAN bus wiring problems, or failed ECU. Systematic diagnosis starts at the gateway then works outward.

Step-by-Step Operation: Network Communication Flow

Example: Accelerator Pedal to Engine Response

Understanding how networks coordinate real-world functions reveals the sophistication behind simple driver actions. Let’s trace the complete sequence from pressing the accelerator pedal to engine response:

1. Driver input: You press the accelerator pedal. The pedal assembly contains a position sensor that outputs 0-5 volt analog signals proportional to pedal travel.

2. Local ECU processing: The pedal position sensor connects to a small ECU integrated into the pedal assembly. This ECU samples both potentiometers, verifies they agree, converts the analog voltage to a digital percentage (0-100%), and packages this into a CAN message.

3. CAN transmission: The pedal ECU transmits the message on the powertrain CAN bus every 10 milliseconds. Since the message has a relatively low identifier (high priority), it typically wins arbitration immediately.

4. Bus arbitration: If multiple nodes try to transmit simultaneously, CAN’s arbitration resolves the conflict without corrupting any messages.

5. Engine ECU reception: The engine control ECU monitors the bus and recognizes the pedal position message. It receives the payload, verifies the CRC checksum, and sends an ACK bit confirming reception.

6. Engine processing: The engine ECU combines pedal position with current engine speed, coolant temperature, air temperature, manifold pressure, and oxygen sensor feedback to calculate optimal throttle body opening, fuel injection timing, and ignition timing.

7. Actuator control: The engine ECU commands the throttle body to the calculated position via direct wire connection. Simultaneously, it adjusts fuel injection pulse width through direct injector control.

8. Total response time: From pedal press to throttle movement: typically 15-25 milliseconds. The network communication adds only 1-2 milliseconds. For comparison, human reaction time is 150-300 milliseconds, so network delay is negligible.

Example: ABS Intervention Network Coordination

Anti-lock braking demonstrates tight coordination between multiple systems through vehicle networks:

1. Wheel speed sensors: Four wheel speed sensors generate AC voltage signals proportional to wheel rotation speed. These connect directly to the ABS ECU via dedicated wires.

2. ABS ECU monitoring: The ABS ECU samples wheel speeds 50-100 times per second. It broadcasts this data on chassis CAN every 20 milliseconds so other systems can use it.

3. Lock detection: During hard braking, if one wheel decelerates much faster than others, the ABS algorithm detects impending lock within 5-10 milliseconds.

4. Brake intervention: The ABS ECU commands hydraulic modulator valves via direct electrical connections. These valves rapidly modulate brake pressure—typically 10-15 cycles per second.

5. Status broadcast: While modulating brake pressure, the ABS ECU broadcasts intervention status on chassis CAN every 10 milliseconds.

6. ESC coordination: The ESC ECU receives the ABS status and other sensor inputs. If it detects vehicle instability, ESC calculates required corrections.

7. Engine torque reduction: ESC broadcasts a torque reduction request on chassis CAN. The powertrain gateway forwards this to the engine ECU, which reduces throttle opening and/or retards ignition timing within 5 milliseconds.

8. Dashboard notification: The ABS status messages route through the gateway to body CAN. The instrument cluster receives these messages and illuminates the ABS warning light.

This example shows how modern vehicle safety systems depend completely on network communication for coordinated brake-engine intervention.

Location and Access: Network Connection Points

OBD-II Diagnostic Port

The OBD-II (On-Board Diagnostics II) port provides standardized access to vehicle networks. Required on all vehicles sold in North America since 1996, this 16-pin connector follows SAE J1962 specification.

Physical location is mandated: under the dashboard on the driver’s side, within arm’s reach of the steering wheel. Most vehicles place it directly above the pedals. The port may be exposed or behind a removable cover.

Pin configuration follows standardized assignments:

- Pin 4 and 5: Chassis ground

- Pin 16: Battery positive 12V

- Pin 6: CAN High (CANH)

- Pin 14: CAN Low (CANL)

Modern vehicles (2008+) use primarily pins 4, 5, 6, 14, and 16—the CAN interface has become universal.

Network access through OBD-II typically connects to the gateway module. The gateway bridges the diagnostic CAN bus to all other vehicle networks. When you scan for codes, your scan tool sends standardized requests that the gateway routes to every ECU and collects responses.

Common diagnostic uses include reading diagnostic trouble codes from all ECUs, clearing codes after repairs, monitoring live sensor data, performing active tests, programming ECU software updates, and monitoring CAN bus traffic for network diagnostics.

Network Topology Physical Layout

Understanding where network wiring physically routes helps diagnose connection problems and avoid damaging cables during repairs.

CAN bus routing typically follows the vehicle’s spine. The twisted pair runs under the dashboard (left to right), drops down the center console, and continues under the vehicle’s floor to the rear. The CAN pair usually has distinctive orange/orange-white or yellow/yellow-white coloring, though color codes aren’t standardized across manufacturers.

LIN bus routing is local to each cluster. A door module’s LIN bus might extend 1-2 meters from the door to the nearby body controller. Seat LIN buses run under the seat to the seat control module.

Ethernet backbone routing in zonal architecture follows major trunk paths. Thick shielded Ethernet cables run from the central computer location to left-front, right-front, rear-left, and rear-right zonal controllers.

Connector locations concentrate at strategic junction points: firewall pass-throughs, door jambs, under seats, behind bumpers, and rear hatch/trunk areas. These connectors are the most common failure points due to vibration, moisture, and flexing.

Stub length discipline is critical for CAN reliability at high speeds. The specification requires stubs (branches from the main bus to individual ECUs) under 30 centimeters. Longer stubs create impedance mismatches that cause signal reflections and bit errors.

Termination resistor locations: CAN buses require 120-ohm termination resistors at both physical ends. These are typically integrated into ECUs at the extreme ends of the bus—for example, the engine ECU at the front and the fuel pump controller at the rear.

Common Failure Modes and Diagnostics

Bus Communication Errors

Network communication failures manifest in various ways depending on severity and location. Understanding these patterns helps isolate problems quickly.

Complete network failure symptoms include multiple systems non-responsive simultaneously, scan tool unable to communicate with any ECUs, vehicle may not start, dashboard warning lights illuminate together, and U-codes stored in multiple modules. Complete failures usually indicate physical damage—severed wire, shorted wires, or total gateway failure.

Partial network failure symptoms include some ECUs responding to scan tool while others don’t, certain systems working intermittently, multiple U-codes from different modules, and functionality partially retained. Partial failures suggest localized wiring damage or individual ECU failure.

Intermittent communication errors are notoriously difficult to diagnose. Symptoms include occasional U-codes that clear and return, systems working most of the time but occasionally malfunctioning, and error messages that come and go. Common causes include corroded connectors making/breaking contact with vibration, loose connector locks, damaged wire insulation creating intermittent shorts, and failing transceivers that work when cool but fail when hot.

Physical Layer Failures

Open circuit (broken wire) symptoms include partial or complete network failure, CANH and CANL both stuck at one voltage with no differential signal, and a flat line on both wires when viewed on an oscilloscope. Common causes are cut harness from collision damage, rodent chewing, or incorrect repairs.

Short to ground symptoms include complete network failure, affected wire stuck at 0V, and no signal on shorted wire. Common causes are wire insulation abraded by vibration, pinched connector, or screw through harness.

Short between wires (CANH touching CANL) creates complete network failure with CANH and CANL at the same voltage and no differential signal possible. Common causes include crushed connector, cut harness with exposed copper contact, or liquid intrusion.

Termination resistor problems with missing termination cause signal reflections and occasional bit errors with intermittent operation. Wrong resistor values create similar effects. Checking termination requires disconnecting all ECUs and measuring resistance between CANH and CANL—you should read 60 ohms.

Connector corrosion creates intermittent communication that worsens during rain or high humidity. Visual inspection of connectors often reveals green/white corrosion deposits. Cleaning with electronics cleaner and applying dielectric grease usually resolves the issue.

Diagnostic Procedures (Professional Only)

Professional diagnosis of network problems requires specialized tools and training. The procedures below are for understanding the process, not DIY attempts. Vehicle networks carry safety-critical data—improper diagnosis can create dangerous failures.

1. Scan tool DTC retrieval: Connect a professional scan tool and scan all modules. U-codes specifically indicate network faults. The code pattern reveals which network segment and which modules are affected.

2. Visual inspection: With the network segment identified, inspect physical wiring and connectors in that area. Check door jamb connectors by opening/closing the door while monitoring the scan tool.

3. Multimeter voltage testing: With ignition on and network active, CANH should read 2.5-3.5V and CANL should read 1.5-2.5V with differential voltage swinging ±1-2V.

4. Resistance testing requires disconnecting power, removing all ECU connectors, and measuring CANH to CANL resistance (should be 60 ohms ±5), CANH to ground (should be >10K ohms), and CANL to ground (should be >10K ohms).

5. Oscilloscope waveform analysis provides definitive diagnosis by capturing actual CAN signals and displaying bit-level detail. Professional technicians look for proper voltage levels, clean transitions, correct bit timing, and absence of ringing.

6. ECU isolation testing identifies failing modules by systematically disconnecting ECUs until the network recovers. When you disconnect the faulty ECU, the network should resume normal operation.

When to Consult a Professional

Network diagnosis and repair is complex enough that most vehicle owners should leave this work to trained technicians. Professional service is essential for:

- Any U-code network communication fault

- Intermittent electrical problems affecting multiple systems

- Post-accident ECU replacement requiring programming

- Software updates, TSBs, and recalls

- Warranty repairs

- Safety-critical systems involving brakes, steering, airbags, or engine control

- Lack of proper diagnostic tools (professional scan tools cost $500-$2000 minimum)

Professional shops typically charge 1-2 hours diagnostic time ($100-$300) to isolate network faults, plus repair time. For most vehicle owners, this professional service is more cost-effective than buying tools and spending days diagnosing intermittent problems.

Safety Considerations and Professional Boundaries

Electrical Safety Warnings

While vehicle networks operate at low voltage (12V nominal), improper diagnosis can still create hazards.

Short circuit fire risk: Although 12V won’t shock you, batteries can deliver hundreds of amps. Shorting positive to ground with tools or probes creates massive current flow that instantly heats wires red-hot. This can melt insulation, ignite nearby materials, and cause battery explosion. Always disconnect the battery negative terminal before working on wiring.

Never probe with engine running: Modern vehicles use complex electrical systems where unpredictable voltage spikes can occur. Probing network wiring with the ignition on and engine running risks creating shorts that damage expensive ECUs.

Never disconnect modules with ignition on: Some ECUs contain voltage-sensitive components that can fail if power is removed unexpectedly while active. Always turn the ignition off and wait 2-3 minutes before disconnecting any electrical connector.

Battery disconnect procedure: Before any electrical work: (1) Turn ignition off and remove key, (2) Wait 2-3 minutes for systems to sleep, (3) Disconnect battery negative terminal first, (4) Secure the cable away from the battery post.

Hybrid/EV high voltage: If your vehicle is hybrid or electric, orange cables carry 200-600V. These are lethal voltages requiring special safety procedures. Never work on orange high-voltage cables without specialized training.

Network Integrity Protection

Never splice into CAN/LIN buses unless you have proper training and tools. Aftermarket accessory installations sometimes require network connections. These must be made with proper splice connectors, correct wire identification, minimal stub length (<30cm), professional-grade crimping tools, and dielectric grease for moisture protection.

Aftermarket installations risk: Many aftermarket devices connect to vehicle networks to monitor data or send commands. These installations create several risks including network damage, device failures disabling the vehicle, security vulnerabilities, and voided warranty coverage. Only use aftermarket devices from reputable manufacturers with professional installation.

Connector care: Network connectors must maintain perfect electrical contact. When disconnecting: release locking tabs completely, pull on the connector body (never the wires), inspect pins for corrosion or damage, clean with electronics cleaner if dirty, apply dielectric grease before reconnection, and ensure locking tabs fully engage.

System Complexity Acknowledgment

Modern vehicles contain astounding complexity. A modern mid-range sedan contains 60-80 electronic control units, each running thousands of lines of software. Luxury vehicles exceed 100 ECUs.

Interdependencies everywhere: Systems that seem unrelated often depend on each other through the network. The transmission needs engine data. The HVAC system monitors vehicle speed. The instrument cluster displays information from dozens of modules. A fault in one system can cause cascading failures in others.

Software-dependent operation: Many vehicle functions exist entirely in software with no mechanical fallback. Electronic throttle control, brake-by-wire, and electric power steering have no manual override. If the network fails, these systems stop working.

Diagnostic complexity: Professional diagnostic equipment costs $10,000-$50,000 for comprehensive coverage. Wiring diagrams for one vehicle can span 3,000 pages. Training courses for network diagnosis last weeks.

Parts availability: Network components like gateway modules and specialized connectors aren’t available at typical auto parts stores. Expect longer wait times and higher costs.

Programming requirements: Replacing many network-connected ECUs requires programming with OEM software to configure the module for your specific vehicle. Dealer programming typically costs $100-300.

Understanding this complexity provides realistic expectations. Simple tasks like reading codes, replacing obviously damaged connectors, or cleaning corrosion remain accessible. Complex diagnosis and programming require professional resources.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

Revolutionary Impact on Automotive Technology

Vehicle networks transformed automotive design as profoundly as electronic fuel injection or automatic transmissions. Before CAN bus, adding new features meant running more wires—expensive, heavy, and limiting. Networks broke this constraint, enabling sophisticated systems that were previously impossible.

Consider adaptive cruise control. This feature requires coordination between radar sensors, engine control, transmission, and brakes. Without networks, the hard-wired connections would be prohibitively complex. CAN bus makes this coordination straightforward. The network infrastructure is reusable across features, so adding new functions becomes primarily a software exercise.

Modern vehicles offer hundreds of features. Heated seats, adaptive suspension, lane keeping, blind spot monitoring, adaptive headlights, gesture controls—each builds on the network foundation. Manufacturers can offer extensive feature sets economically because the communication infrastructure is already in place.

The environmental impact shouldn’t be overlooked. Lighter vehicles burn less fuel and produce fewer emissions. Network-enabled weight reduction contributes meaningfully to efficiency improvements. A 30-kilogram harness weight reduction might improve fuel economy by 0.5%, which multiplied across millions of vehicles represents significant environmental benefit.

Safety improvements from networks are equally important. ABS, ESC, and ADAS features directly prevent accidents. These systems depend entirely on network communication to coordinate multiple sensors and actuators. The guaranteed timing and reliability of automotive networks enable safety features that save thousands of lives annually.

The Future: Software-Defined Vehicles

The industry is transitioning toward software-defined vehicles where functionality exists primarily in code rather than hardware. This shift is enabled by and dependent on high-bandwidth vehicle networks.

Centralized compute architecture places powerful processors at the vehicle’s center, running all control software. Peripheral zonal controllers act as remote input/output devices connected via Ethernet backbone. This resembles cloud computing architecture.

Over-the-air updates become practical with Ethernet bandwidth. Tesla pioneered frequent OTA updates that improve vehicle functionality post-purchase. Traditional OEMs are following. Future vehicles will receive monthly updates adding features, fixing bugs, and improving efficiency.

Autonomy depends on networks: Self-driving vehicles generate terabytes of sensor data daily. Processing requires distributed computing with sensor fusion, path planning, and vehicle control. This is only feasible with high-bandwidth networks like Automotive Ethernet.

Cybersecurity becomes critical: As vehicles gain Internet connectivity and software control extends to safety-critical systems, cybersecurity rises to paramount importance. Networks must implement authentication, encryption, and intrusion detection.

Educational Understanding vs. DIY Repair

This article aimed to provide deep understanding of vehicle networks. This knowledge serves multiple purposes depending on your situation.

For vehicle owners: Understanding networks helps you make informed decisions about repairs. When a shop quotes diagnostic time for network issues, you understand why this takes hours. When they recommend replacing a gateway module, you comprehend why this costs more than traditional repairs.

For DIY enthusiasts: You can handle certain network-related tasks confidently. Reading trouble codes, understanding U-codes, and following basic diagnostic procedures are accessible. Cleaning corroded connectors, checking wiring damage, and verifying battery connections solve many network issues. Know when to escalate to professionals.

For automotive enthusiasts: Understanding vehicle networks deepens appreciation for modern automotive engineering. The sophistication hidden beneath familiar exteriors rivals aerospace systems. Networks enable features we take for granted.

When Professional Service Is Essential

Draw clear boundaries between educational understanding and repair attempts. Professional service is essential for any U-code network communication fault, intermittent problems affecting multiple systems, post-accident ECU replacement, software updates and recalls, warranty repairs, and safety-critical systems.

Professional shops invest heavily in tools, training, and information systems. This investment enables efficient diagnosis and proper repairs. For network-related problems, professional service is usually more economical than DIY attempts.

Final Recommendation

Modern vehicle networks represent engineering sophistication that makes advanced features possible while reducing cost and weight. Understanding network operation empowers better vehicle ownership. You can communicate effectively with service providers. You recognize realistic pricing. You make informed decisions based on understanding.

However, complexity and safety implications mean most network repairs should remain with trained professionals. The boundary isn’t arbitrary—it reflects tool requirements, safety considerations, and realistic DIY capabilities. Respecting this boundary protects both your vehicle and your safety.

For vehicle-specific repair procedures and comprehensive service manuals, explore our collection organized by manufacturer. Whether you drive a Ford, Toyota, Honda, or any other make, professional-grade repair information helps you understand your vehicle better.

Browse Repair Manuals: