Modern vehicle steering feels effortless—turn the wheel and your car responds instantly with precision. This seamless control comes from the rack and pinion steering system, the most common steering mechanism in vehicles today, found in over 85% of cars, SUVs, and light trucks on the road. From compact sedans to performance sports cars, this elegantly simple yet highly effective system has revolutionized how we control our vehicles.

Understanding how your rack and pinion steering works is essential for recognizing problems early, making informed maintenance decisions, and knowing when professional service is required. Whether you’re hearing unusual noises when turning, noticing fluid leaks under your vehicle, or simply want to understand this critical safety system better, this knowledge empowers you to keep your vehicle safe and responsive.

This comprehensive guide explains the complete operation of rack and pinion steering systems, from basic mechanical principles to modern hydraulic and electric power assist technologies. You’ll learn exactly how the system converts your steering input into wheel movement, recognize warning signs of failure before they become dangerous, understand realistic replacement costs, and discover proper maintenance practices that can extend your system’s life well beyond 100,000 miles. For those interested in the broader steering system context, our guide on how hydraulic power steering works provides additional technical depth on the hydraulic assist components.

What Is Rack and Pinion Steering?

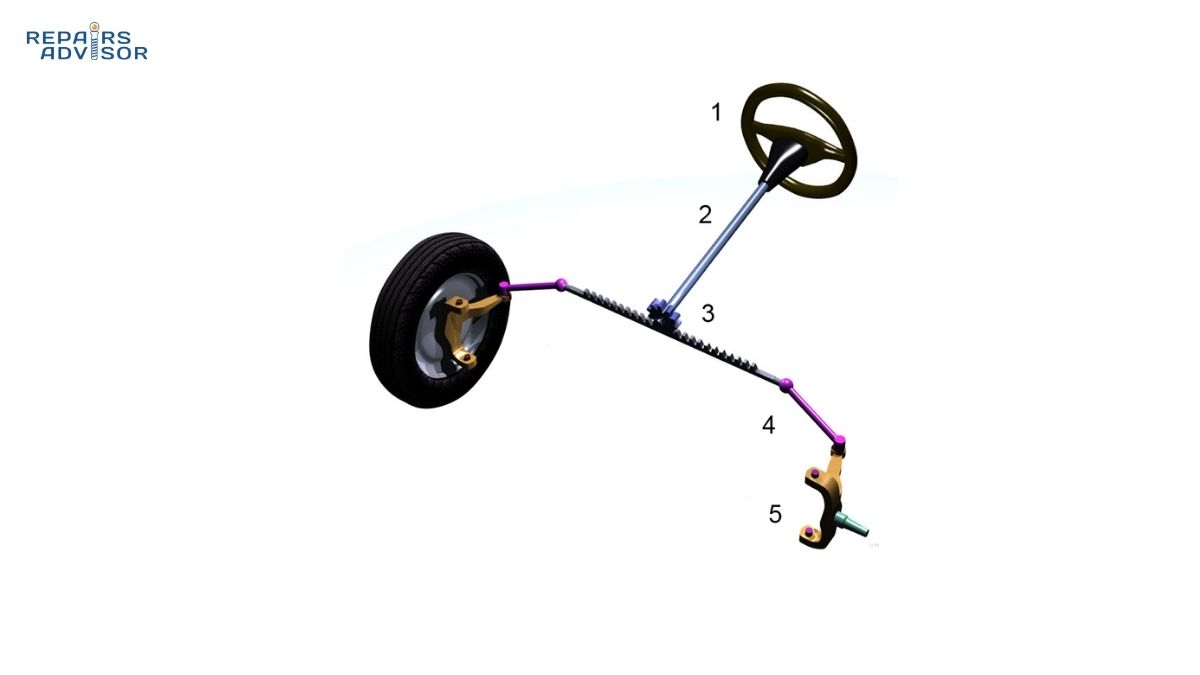

Rack and pinion steering is a mechanical system that converts the rotational motion of your steering wheel into the linear side-to-side movement needed to turn your vehicle’s front wheels. The system gets its name from its two primary components: the rack, a flat metal bar with gear teeth cut along one edge, and the pinion, a small circular gear that meshes with those teeth. When you turn your steering wheel, the pinion gear rotates and moves the rack left or right, which then pushes or pulls on the tie rods connected to your wheels.

This fundamental design represents one of engineering’s most elegant solutions to vehicle control. Unlike more complex steering mechanisms, rack and pinion systems achieve precise control with remarkable simplicity—typically just two gears working in harmony to translate your input into immediate wheel response.

Historical Development and Industry Adoption

While the rack and pinion mechanism has existed for centuries in various mechanical applications, its automotive use began relatively recently in historical terms. BMW produced the first automotive rack and pinion gearbox in the 1930s, recognizing the system’s potential for precise vehicle control. However, American manufacturers were slow to adopt this technology, continuing to rely on recirculating ball steering systems that had served well for decades.

Ford became the first American automaker to embrace rack and pinion steering, introducing it on the 1974 Mustang II and Ford Pinto. American Motors Corporation (AMC) followed shortly after with the 1975 Pacer. General Motors and Chrysler didn’t manufacture vehicles with rack and pinion steering until the 1980s, but once they made the switch, the industry never looked back. Today, rack and pinion steering has become the overwhelming standard across the automotive industry.

Why Rack and Pinion Became the Industry Standard

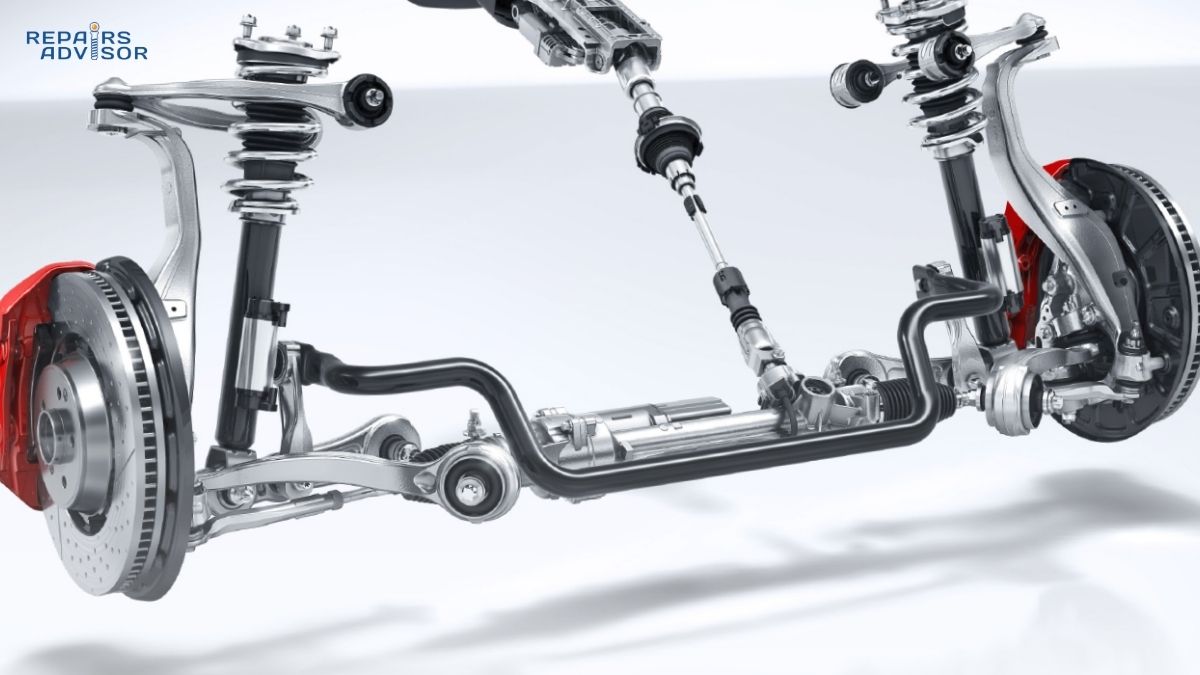

The transition from recirculating ball to rack and pinion steering wasn’t arbitrary—it reflected genuine engineering advantages that benefit both manufacturers and drivers. The rack and pinion design features significantly fewer moving parts than recirculating ball systems, which translates to higher reliability and lower manufacturing costs. With only two main gears compared to the complex assembly of a recirculating ball gearbox, there are simply fewer components that can wear or fail.

Weight reduction represents another critical advantage. Rack and pinion systems weigh considerably less than recirculating ball assemblies, improving front-end weight distribution and contributing to better fuel economy. Every pound removed from a vehicle’s front end improves handling dynamics and reduces the energy required for acceleration and braking.

The precision and responsiveness of rack and pinion steering also surpass older designs. The direct mechanical connection between the steering wheel and the wheels provides excellent road feedback, allowing drivers to feel exactly what the tires are doing. This communication between driver and vehicle is particularly valued in performance applications, where precise control can mean the difference between staying on course and losing control. Our article on how steering geometry works explores how rack and pinion systems integrate with alignment angles to optimize this steering response.

Modern vehicle packaging requirements favor rack and pinion designs as well. The compact, tubular configuration fits more easily into contemporary vehicle architectures, particularly front-wheel-drive platforms where engine placement leaves limited space for steering components. Additionally, rack and pinion systems integrate more seamlessly with power steering assistance, whether hydraulic or electric, making them ideal for today’s efficiency-focused automotive engineering.

Core Components and System Design

Understanding the individual components of a rack and pinion steering system reveals how this elegantly simple mechanism achieves such precise control. Each component plays a specific role in translating your steering input into wheel movement while maintaining durability under constant use.

The Rack Assembly

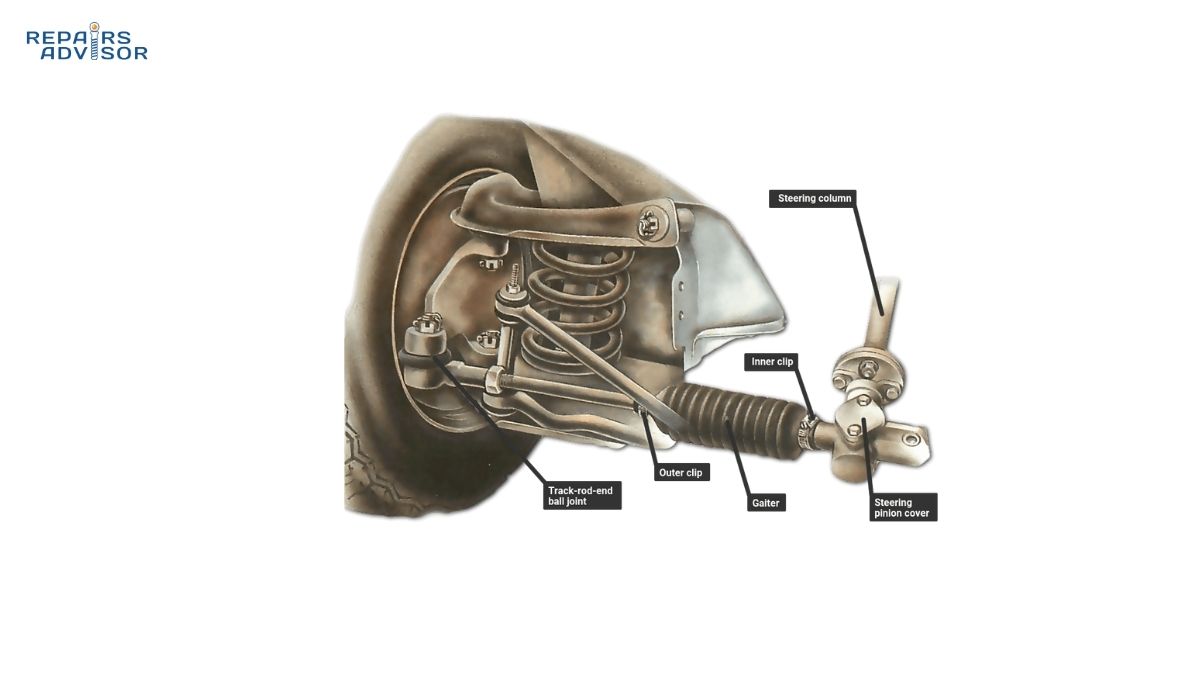

The rack forms the heart of the system—a precisely machined metal bar typically measuring 18 to 36 inches in length depending on vehicle size and design. One side of this bar features gear teeth cut with exacting precision, as these teeth must mesh perfectly with the pinion gear throughout the rack’s entire range of motion. The rack is enclosed within a protective tubular housing that shields it from road debris, moisture, and contaminants while containing the lubricating grease essential for smooth operation.

At each end of the rack, flexible rubber or synthetic boots create a seal where the rack extends through the housing. These rack boots serve multiple critical functions: they prevent contamination from entering the housing, retain lubricating grease, and in power-assisted systems, they prevent hydraulic fluid from escaping. The condition of these boots often provides the first visual indication of rack problems, as tears or damage can allow fluid leakage or dirt intrusion that accelerates wear.

The rack mounts to the vehicle’s frame or subframe through specialized bushings that allow a minimal amount of movement for noise and vibration isolation while maintaining the rigid positioning necessary for precise steering control. These mounting bushings represent a carefully engineered compromise—too soft and the steering feels vague and imprecise; too hard and road vibrations transmit harshly through the steering wheel.

The Pinion Gear

The pinion gear, though small in size—typically just three-quarters to one and a half inches in diameter—plays an outsized role in system function. This circular gear attaches to the base of the steering column and features precisely cut teeth that engage with the rack’s gear teeth. The pinion rotates within sealed bearings that support smooth rotation while maintaining the exact positioning required for proper gear mesh.

The pinion’s size relative to the rack determines the steering ratio, which we’ll explore in detail shortly. This ratio affects how many turns of the steering wheel are required to move the wheels from full left to full right lock, balancing ease of steering against responsiveness. The input shaft extending from the pinion gear connects to the steering column through universal joints that accommodate the angle change between the column and the rack, which are detailed in our guide on how steering columns work.

Tie Rods and Steering Linkage

The rack’s lateral movement must be transferred to the wheels, and this critical connection happens through the tie rod assembly. Inner tie rods connect directly to the threaded ends of the rack using specialized connections that allow the tie rod to articulate as the suspension moves up and down. These inner tie rods typically feature ball and socket joints sealed within protective boots similar to those covering the rack ends.

Outer tie rods connect the inner tie rods to the steering knuckles at each front wheel. These outer tie rods are adjustable in length, which allows technicians to precisely set the vehicle’s toe alignment—the angle at which the wheels point relative to the vehicle’s centerline. Ball joints at the outer ends allow the tie rods to articulate in multiple planes as the suspension compresses and extends while the wheels turn. The complete tie rod assembly from rack to wheel creates a robust yet flexible linkage that accommodates all the complex motions required during normal driving. For more details on these critical components, see our comprehensive article on how tie rods, ball joints, and columns work.

Housing and Mounting Architecture

The rack housing serves as more than a simple protective tube—it’s a precision-machined component that maintains exact alignment of the rack within the vehicle. The housing features mounting points that bolt to the vehicle’s subframe or front crossmember using brackets and bushings. These mounting points must position the rack with extreme accuracy, as even small misalignments can cause binding, premature wear, or imprecise steering response.

Different manufacturers use various mounting configurations, but all share the same goal: rigid attachment that resists the substantial forces generated during steering while allowing minimal movement for noise and vibration isolation. The bushings at these mounting points wear over time, and excessive bushing wear can introduce play into the steering system that manifests as a loose or vague feeling at the steering wheel.

Two Main Design Configurations

Rack and pinion systems come in two primary configurations that affect packaging and design flexibility. The end take-off design, which is far more common, attaches the inner tie rods to the ends of the rack via threaded connections. This straightforward configuration simplifies manufacturing and makes the most efficient use of the rack’s travel.

The less common center take-off design bolts the tie rods to the middle section of the steering rack rather than the ends. This configuration offers different packaging advantages in specific vehicle architectures and can provide benefits in terms of bump steer control—the tendency for steering to change as the suspension compresses and extends. However, the added complexity means most modern vehicles use the simpler and more reliable end take-off design.

How the Mechanical System Works

The beauty of rack and pinion steering lies in its straightforward operation, converting rotational motion to linear movement through a simple gear interaction. Understanding this process reveals why the system has become the overwhelming favorite in modern automotive engineering.

The Basic Operating Principle

When you turn your steering wheel, that rotation travels down the steering column to the pinion gear at the base. As the pinion gear rotates, its teeth engage with the teeth cut into the rack, and this meshing action forces the rack to move laterally within its housing. If you turn the steering wheel to the right, the pinion rotation pushes the rack to the right; turning left produces the opposite motion.

The rack’s lateral movement directly actuates the tie rods connected at each end. The right tie rod pushes against the right steering knuckle while the left tie rod pulls on the left steering knuckle (or vice versa depending on turn direction), causing both front wheels to turn in the desired direction. This direct mechanical linkage from steering wheel to wheels creates the immediate response and precise control that drivers appreciate, with minimal slack or play in the system. The steering knuckles themselves, which serve as the critical pivot points for wheel movement, are explained in detail in our article on how steering knuckles work.

The entire motion happens smoothly and continuously as you turn the steering wheel. Unlike systems with multiple linkages and pivot points, rack and pinion steering maintains a direct, proportional relationship between your input and the wheels’ response throughout the full range of steering motion.

Understanding Steering Ratio

The steering ratio represents one of the most important characteristics of any steering system, defining the relationship between how far you turn the steering wheel and how much the wheels actually turn. This ratio is calculated by dividing the steering wheel rotation in degrees by the resulting wheel turn in degrees. For example, if you turn the steering wheel 360 degrees and your wheels turn 20 degrees, your vehicle has an 18:1 steering ratio (360 ÷ 20 = 18).

Typical steering ratios for modern vehicles range from 12:1 to 20:1, with the choice reflecting the intended vehicle use and character. A higher ratio—say, 18:1 or 20:1—means you must turn the steering wheel more to achieve a given wheel angle. This makes steering easier physically, as the mechanical advantage reduces the force required, but it also makes the steering less responsive since more wheel rotation is needed for each degree of tire turn. Trucks and SUVs often use higher ratios to make low-speed maneuvering of heavy vehicles manageable without excessive arm strain.

Lower steering ratios, typically 12:1 to 15:1, characterize performance-oriented vehicles where quick steering response takes priority over reduced effort. These ratios require fewer steering wheel rotations to turn the wheels through their full range, creating the immediate, responsive feel that performance drivers value. The trade-off is that more force is required at the steering wheel, though modern power steering systems mitigate this disadvantage.

Most vehicles require three to four complete rotations of the steering wheel to move from full left lock to full right lock—this is what technicians mean when they refer to “lock-to-lock turns.” The specific number depends on the steering ratio and the maximum angle the suspension allows the wheels to turn.

Variable Ratio Steering Technology

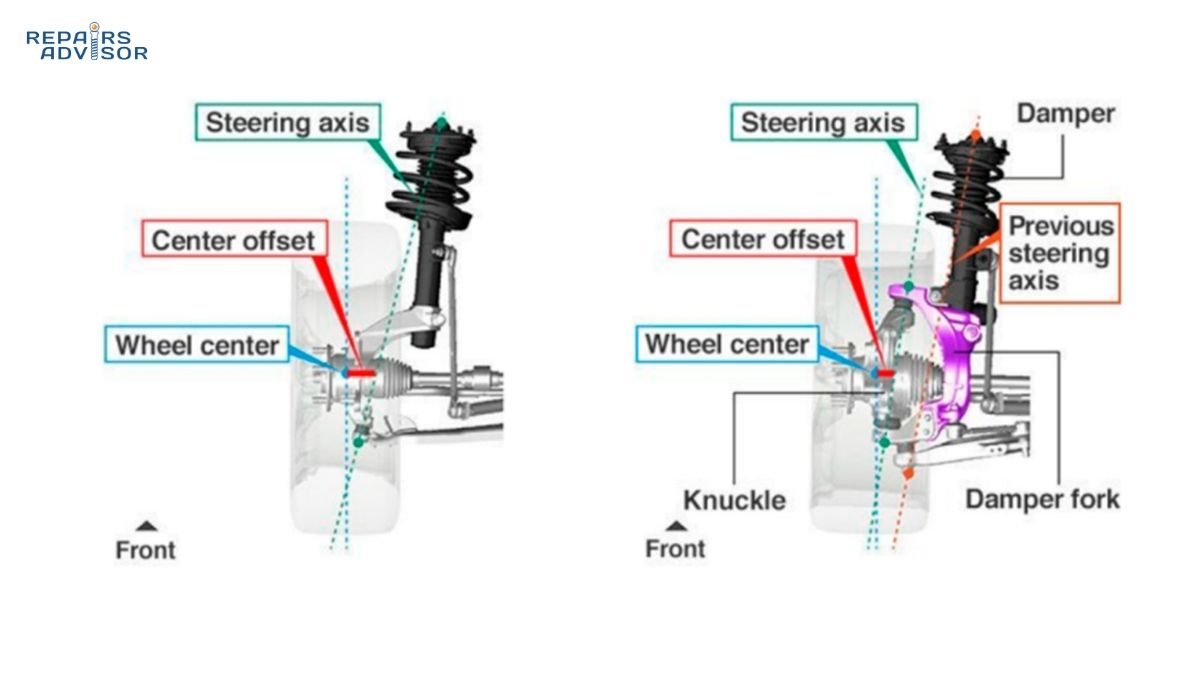

Some advanced rack and pinion systems employ variable ratio technology, using different tooth pitch (spacing) on the rack itself. The center section of the rack features teeth with one pitch, while the sections toward each end use a different pitch. This clever design provides the best of both worlds: higher ratio (less sensitive) steering when the wheels are near center position for stable, relaxed highway driving, and lower ratio (more sensitive) steering as you approach full lock for easier parking maneuvers.

The transition between these different ratios happens smoothly and progressively as you turn the steering wheel, so drivers typically don’t notice the change consciously. They simply experience stable, confidence-inspiring highway tracking combined with surprisingly easy parking lot maneuverability—advantages that would traditionally require conflicting steering ratio choices.

Variable ratio steering has become increasingly common on luxury vehicles and performance cars where the refinement and responsiveness benefits justify the additional manufacturing complexity and cost.

Mechanical Advantage and System Efficiency

The gear reduction provided by the pinion-to-rack interaction creates mechanical advantage that reduces the force you must apply at the steering wheel. Even without power steering assistance, this mechanical advantage makes it possible to turn the wheels, though significant effort is required, especially when the vehicle is stationary or moving slowly.

In manual rack and pinion systems without power assistance, you’re working against tire friction with the road, the weight on the front wheels, and the resistance of the suspension system. This combination requires substantial physical effort, which is why manual steering has largely disappeared except in some lightweight sports cars where enthusiasts value the unfiltered road feedback despite the physical workout.

The typical manual rack and pinion system requires 3 to 4 complete steering wheel rotations from lock to lock, representing a reasonable compromise between steering effort and responsiveness. With modern power steering systems—whether hydraulic or electric—this same mechanism becomes effortless to operate while maintaining the precision and directness that makes rack and pinion steering so successful.

Power Steering Systems: Hydraulic vs. Electric

While the basic rack and pinion mechanism provides precise steering control, the physical effort required to turn modern tires—especially wider performance or all-terrain tires—would be exhausting without power assistance. Two distinct technologies have evolved to provide this assistance: hydraulic power steering, which has served reliably for over 50 years, and electric power steering, which now dominates new vehicle production.

Manual Rack and Pinion: Pure Mechanical Connection

Before exploring power-assisted systems, it’s worth understanding manual rack and pinion steering, as this represents the pure mechanical system without any augmentation. In manual steering, your physical effort at the steering wheel provides all the force needed to turn the wheels through direct mechanical linkage. There’s no pump, no motor, no fluid—just gears, metal, and your muscles.

Manual steering offers one significant advantage: unfiltered road feedback. Every texture change in the pavement, every variation in grip, communicates directly through the steering wheel to your hands. Driving enthusiasts often prize this pure mechanical connection, describing it as “communicative” or “involving.” Some lightweight sports cars still offer manual steering as standard or optional equipment, accepting the physical effort as a worthwhile trade for this tactile communication.

The disadvantages, however, explain why manual steering has virtually disappeared from the market. At low speeds—especially when parking or maneuvering in tight spaces—the force required to turn the wheels becomes substantial, sometimes requiring considerable physical strength. Front-wheel-drive vehicles, which carry significant weight over the front wheels, amplify this difficulty. Additionally, wider tires, which have become standard for safety and handling, increase rolling resistance and make steering even harder.

Despite these limitations, manual rack and pinion systems demonstrate remarkable reliability. With no hydraulic seals to leak or electric motors to fail, a well-maintained manual system can last the life of the vehicle. If you’re working on a classic car or lightweight sports car with manual steering, the system’s simplicity makes it relatively straightforward to service and rebuild.

Hydraulic Power Steering: The Proven Standard

Hydraulic power steering has assisted drivers for over five decades, using fluid pressure to reduce steering effort dramatically. The system employs an engine-driven hydraulic pump, typically mounted on the engine’s accessory drive and powered by the serpentine belt. This pump continuously circulates power steering fluid through the system, maintaining pressure between 1,000 and 1,500 PSI depending on vehicle requirements.

The hydraulic rack contains a piston integrated into the rack itself, with fluid chambers on both sides of this piston. A sophisticated control valve, typically integrated into the pinion gear assembly, senses torque applied to the steering wheel and responds by directing high-pressure fluid to one side of the piston while allowing fluid from the other side to return to the reservoir. This pressure differential assists the rack’s movement in the direction you’re steering, making the effort feel light and effortless.

The beauty of this hydraulic system lies in its proportional response. Light steering inputs produce modest assistance, while more forceful inputs—such as when parking or making sharp turns at low speed—generate greater hydraulic assist. The system operates continuously whenever the engine runs, maintaining pressure and standing ready to assist steering at any moment. For a detailed exploration of these hydraulic components and their operation, our guide on how hydraulic power steering works provides comprehensive technical information.

Hydraulic power steering offers several advantages that explain its long dominance. The technology is thoroughly proven, with over 50 years of refinement creating highly reliable systems. Hydraulic assist provides strong force multiplication, making even heavy vehicles with large tires easy to maneuver. Many driving enthusiasts prefer hydraulic systems for their road feel, as the fluid medium provides more natural feedback than some electric systems. When repairs become necessary, the relative simplicity of hydraulic components often makes them more economical to fix compared to electronic alternatives.

However, hydraulic systems carry notable disadvantages that have driven the industry toward electric alternatives. The engine-driven pump consumes power continuously whether you’re steering or not, reducing fuel economy by approximately 1 MPG even during highway cruising when no steering assist is needed. The system requires regular fluid maintenance, with manufacturers typically recommending fluid changes every 50,000 to 75,000 miles. Multiple components—pump, hoses, reservoir, rack seals—represent potential failure points, and hydraulic fluid leaks are a common issue on higher-mileage vehicles. The added weight of pump, fluid, hoses, and reservoir also works against modern efficiency goals.

Electric Power Steering: The Modern Solution

Electric Power Steering (EPS) has rapidly displaced hydraulic systems in new vehicle production, leveraging electric motors and sophisticated electronic controls to provide steering assistance. Rather than a continuously running hydraulic pump, EPS uses an electric motor that attaches either to the steering column, the pinion gear, or directly to the rack itself, depending on the specific system design.

The operation relies on several sensors working in concert. A torque sensor detects when you apply force to the steering wheel and measures how much force you’re applying. A steering angle sensor tracks the wheel’s position. The vehicle’s speed sensor provides additional input, and all this information flows to an electronic control module (ECU) that calculates exactly how much assistance to provide and commands the electric motor accordingly.

This sensor-based approach allows remarkable flexibility. The ECU can vary assistance levels based on vehicle speed—providing substantial help during low-speed parking maneuvers while reducing assistance at highway speeds for better stability and road feel. The system can integrate seamlessly with advanced driver assistance features like lane-keeping assist and automated parking. Different driving modes can alter steering characteristics at the touch of a button, offering “comfort,” “sport,” or “normal” steering calibrations. For those interested in the sophisticated control algorithms that make this possible, our article on how EPS control systems work provides detailed technical insight.

Electric power steering delivers several compelling advantages that explain its market dominance. The system only consumes electrical power when you’re actually steering, improving fuel economy by 2 to 3% compared to hydraulic systems—a significant benefit in an era of strict efficiency regulations. No hydraulic fluid means no fluid to change, leak, or contaminate, reducing maintenance requirements substantially. The electric motor and electronics weigh less than hydraulic pump, hoses, and fluid, supporting lightweight vehicle design. The programmable nature of electric assist allows manufacturers to tune steering feel precisely and adapt it for different driving modes or conditions.

Electric systems do present some trade-offs. Initial manufacturing costs run higher due to sophisticated electronics and precision motors, though these costs continue to decline with volume production. Some drivers find EPS lacking in road feel compared to hydraulic systems, though the best modern systems have largely addressed this criticism through advanced programming. The electric motor represents a potential failure point, though actual failures remain relatively rare. When problems do occur, diagnosis and repair require specialized equipment and training that not all shops possess.

The integration of electric motors with sophisticated control systems enables features impossible with hydraulic steering, explaining why manufacturers have embraced EPS so thoroughly. The detailed operation of these motor control systems is covered in our technical article on how EPS motor and controller works.

Common Problems and Warning Signs

Like any mechanical system subjected to constant use and exposure to harsh conditions, rack and pinion steering systems eventually wear and develop problems. Recognizing the warning signs early allows you to address issues before they compromise safety or lead to more expensive repairs.

Steering Difficulty and Excessive Effort

If your steering wheel becomes noticeably harder to turn, especially at low speeds or when parking, this indicates a problem requiring immediate attention. The stiff, tight feeling often points to low power steering fluid in hydraulic systems—the first thing to check. If fluid level is adequate, the problem may lie with internal rack damage, a failing power steering pump (on hydraulic systems), or a malfunctioning electric assist motor (on EPS systems).

In hydraulic systems, a failing pump may still produce some pressure but not enough for normal operation. The pump might make whining or groaning noises, especially when turning the wheel at idle. In electric systems, the assist motor may have failed entirely or the control module may have detected a problem and reduced or eliminated assistance as a safety measure.

Steering difficulty represents a serious safety concern. If you suddenly lose power assist while driving, the steering doesn’t fail completely—the mechanical connection still works—but the effort required increases dramatically and dangerously. What would normally be an easy steering correction becomes a two-handed wrestling match, particularly at low speeds. Never ignore increasing steering effort; have the system diagnosed professionally as soon as possible.

Loose or Unresponsive Steering

The opposite problem—steering that feels loose, vague, or unresponsive—can be equally dangerous. Excessive play in the steering wheel means you can turn the wheel noticeably before the wheels begin to respond. This play might manifest as “wandering,” where the vehicle drifts left or right on the highway and requires constant correction to maintain a straight path.

A “dead spot” in steering response indicates worn areas in the rack gear teeth or loose mounting bushings. The dead spot typically occurs when the wheels are pointed straight ahead, exactly where you need the most precise control during highway driving. As you turn the wheel through this worn section, there’s a moment where nothing happens before the steering suddenly engages. This unpredictable behavior makes the vehicle difficult to control and unsafe to drive.

Loose steering can result from several issues: worn rack teeth, damaged pinion gear, loose mounting bushings, or problems with tie rods and ball joints. Sometimes multiple issues combine to create severe play. While some play in these systems may seem minor, it affects your ability to control the vehicle precisely and can worsen rapidly. Understanding the entire steering linkage system, as explained in our guide on how tie rods, ball joints, and columns work, helps in identifying whether the rack itself is at fault or if related components are contributing to the problem.

Unusual Noises During Steering

Strange sounds when turning the steering wheel often provide the first audible warning of rack problems. Grinding noises typically indicate metal-on-metal contact, suggesting inadequate lubrication within the rack housing or severely worn gear teeth. This grinding might be subtle at first but usually worsens progressively as the damage accelerates.

Clunking sounds, especially at full steering lock (when the wheel is turned as far as it will go in either direction), point to severe internal component wear or damage to the rack’s internal stops. A whining or squealing noise that changes with steering input often originates from the power steering pump in hydraulic systems, though it can also indicate air in the hydraulic fluid or a failing pump.

Any unusual noise deserves investigation. The sounds represent mechanical components operating outside their design parameters, and continuing to drive with these symptoms accelerates damage and increases repair costs. In some cases, the noise provides early warning of problems that could otherwise progress to complete failure.

Power Steering Fluid Leaks

For hydraulic rack and pinion systems, fluid leaks represent one of the most common problems, particularly on vehicles with 100,000+ miles. Power steering fluid appears as a red or pink liquid (though it can darken with age and contamination). You’ll typically find puddles or wet spots under the front of the vehicle, often just behind the front wheels where the rack is located.

Check the rack boots—the rubber or synthetic covers at each end of the rack—for signs of leakage. If these boots appear swollen, wet, or are dripping fluid, the internal rack seals have failed and are allowing pressurized fluid to escape. Sometimes a slow leak may not create obvious puddles but will cause the power steering fluid reservoir to require frequent topping up.

Leaking power steering fluid causes multiple problems. The immediate issue is loss of hydraulic pressure, which reduces or eliminates power assist. As fluid level drops, the pump can draw in air, creating foam and noise while further reducing system effectiveness. Leaked fluid on the ground presents environmental concerns and can damage asphalt driveways. Most seriously, continued operation with low fluid damages the pump, potentially turning a simple seal replacement into a more expensive pump and rack replacement.

Address fluid leaks promptly—not when the reservoir runs dry. Adding fluid repeatedly without fixing the leak is poor practice that leads to more expensive repairs. If you’re also experiencing issues with other suspension components, our diagnostic guides on how to tell if you have a bad ball joint and how to spot a bad control arm can help determine if multiple steering and suspension components need attention.

Burning Oil Smell: Critical Warning Sign

If you smell something like burning oil while driving and notice it seems to come from the front of the vehicle, particularly during or after turning, this could indicate power steering fluid overheating due to excessive friction within the rack. Power steering fluid has a distinctive smell similar to burning oil, though typically sweeter and more acrid.

This symptom demands immediate attention. Pull over as soon as safely possible and shut off the engine. The fluid overheating indicates severe internal problems in the rack, possibly metal-to-metal contact creating dangerous heat buildup. In extreme cases, overheated power steering fluid can ignite, creating a fire hazard. Do not continue driving with this symptom—have the vehicle towed to a repair facility.

Steering Wheel Doesn’t Return to Center

After completing a turn, the steering wheel should naturally return toward the center position as the front wheels seek their straight-ahead alignment. If the wheel doesn’t return or returns sluggishly, the rack may be binding internally. This can also result from improper wheel alignment, worn suspension components, or binding in the steering column itself, but the rack remains a common culprit.

Binding can result from internal corrosion (if rack boots failed and allowed water intrusion), damaged rack teeth, or debris that entered the housing through torn boots. Whatever the cause, this symptom indicates the rack isn’t operating smoothly throughout its range of motion and requires professional diagnosis.

Understanding Failure Causes

Rack and pinion systems fail for several reasons, most commonly simple wear from accumulated mileage. A vehicle with 100,000 to 150,000 miles has made hundreds of thousands of steering inputs, and this repetitive motion gradually wears the gear teeth, seals, and bushings. This is normal wear and not a manufacturing defect or maintenance failure.

Impact damage accelerates wear significantly. Hitting curbs, especially with force, can bend the rack housing, damage teeth, or knock the mounting bushings out of position. Potholes deliver similar shock loads through the tie rods directly into the rack. These impacts explain why urban vehicles with heavy curb parking and pothole exposure often need rack replacement sooner than highway-driven vehicles.

Contaminated or low power steering fluid (in hydraulic systems) causes premature wear. Dirty fluid contains abrasive particles that accelerate wear on precision surfaces. Low fluid levels allow air into the system and reduce lubrication, increasing friction and heat. Using improper fluid types—particularly “universal” fluids that don’t meet manufacturer specifications—can damage seals and reduce lubrication effectiveness.

Torn rack boots accelerate failure dramatically. These boots exist specifically to keep contaminants out and lubricant in. Once a boot tears, road salt, dirt, water, and grit enter the housing and attack the precision-machined surfaces. Torn boots also allow lubricating grease to escape. Regular inspection of boot condition represents one of the most important preventive maintenance steps.

Diagnosis and When to Seek Professional Help

Diagnosing rack and pinion problems involves both simple checks that intermediate DIY mechanics can perform and sophisticated testing requiring professional equipment and expertise. Understanding what you can check yourself versus when to seek professional service saves time, money, and potential safety hazards.

DIY Inspection Steps for Intermediate Mechanics

You can perform several useful diagnostic checks with basic tools and mechanical understanding. Start with the power steering fluid inspection—one of the simplest yet most informative checks. With the engine off, locate the power steering fluid reservoir (typically near the front of the engine bay, often with a dipstick or sight glass). The fluid should appear pink or red and translucent. Dark brown or black fluid indicates contamination and overdue for change. Cloudy or foamy fluid suggests air in the system. Low fluid level, especially if you topped it up recently, indicates a leak somewhere.

For visual leak inspection, safely raise the vehicle on jack stands or use ramps to gain access under the front end. Look for wet spots, fresh fluid, or accumulated dirt/grease around the rack housing and rack boots. The rack boots should feel dry and pliable; if they’re wet, swollen, or torn, the rack is leaking and the boots need replacement at minimum. Check the ground or garage floor where you normally park for fluid puddles—power steering fluid’s red or pink color makes it relatively easy to identify.

Inspect the rack boots carefully with a flashlight. Any tears, cracks, or splits compromise the protective seal. Squeeze the boots gently—they should feel firm with grease inside, not loose and empty. If the boots feel full of liquid rather than grease consistency, internal rack seals have failed and hydraulic fluid has entered the boot area.

During a test drive, listen carefully for unusual noises when turning, particularly grinding, clunking, or whining. Note whether the steering wheel returns to center smoothly after turns. Feel for vibrations through the steering wheel or any dead spots in steering response. Test the steering at various speeds—some problems only manifest during low-speed maneuvering while others appear at highway speeds.

When Professional Diagnosis Becomes Essential

Several symptoms and situations demand professional evaluation rather than DIY diagnosis. Any grinding, clunking, or loud whining noises require expert assessment with the vehicle on a lift for complete inspection. Visible fluid leaks that you can’t easily source should be professionally diagnosed—the leak might come from the rack, but it could also originate from the pump, hoses, or other hydraulic components.

Steering difficulty or excessive play represents a safety concern requiring immediate professional attention. While you might verify fluid level yourself, determining whether the problem lies with the rack, pump, tie rods, ball joints, or other components requires systematic professional diagnosis. Similarly, any burning oil smell demands immediate professional service, as discussed earlier—this is not a symptom to investigate yourself.

Professional mechanics have distinct advantages in rack and pinion diagnosis. They can safely lift the vehicle for complete undercarriage inspection, checking components from angles impossible to see from above or from under jack stands. With the wheels off the ground, they can check for play in tie rod ends versus rack internal wear. They can inspect steering column universal joints and intermediate shaft condition. Most importantly, they can test actual steering effort and measure free play against factory specifications.

For electric power steering systems, professional scan tools can read trouble codes from the EPS control module, providing specific diagnostic information about sensor failures, motor problems, or control module issues. These electronic diagnostics require specialized equipment that DIY mechanics typically don’t possess.

The professional diagnostic process typically begins with a thorough test drive to verify the complaint and note specific symptoms. With the vehicle on the lift, the technician checks rack mounting bushing condition and security. They inspect tie rod ends and ball joints for wear, as these components can mimic or contribute to rack problems. The steering effort is tested both with the engine off (to verify mechanical operation) and running (to test power assist function).

For hydraulic systems, fluid condition is evaluated and the pump tested for proper pressure output. The rack itself is checked for internal leakage by monitoring whether fluid bypasses internally when pressure is applied. Electric systems undergo scan tool diagnosis to check for stored trouble codes and verify sensor operation. Throughout this process, the technician distinguishes between rack problems and issues with related components.

Why Professional Service Matters for Safety

Rack and pinion systems are safety-critical components. Your ability to control your vehicle depends entirely on proper steering system operation. Unlike some maintenance items where DIY work carries minimal risk, steering system work demands precision and expertise. Improper installation can result in immediate steering failure. Incorrect fastener torque can allow components to separate. Failure to properly bleed hydraulic systems or center electric racks can cause dangerous malfunctions.

Wheel alignment is mandatory after rack and pinion replacement. Even if you successfully replace the rack yourself, you’ll need professional alignment service afterward, as the tie rod positions will have changed. Attempting to drive with severely misaligned wheels damages tires rapidly and makes the vehicle difficult to control.

The cost of professional diagnosis—typically $100 to $150—is money well spent for peace of mind and accurate problem identification. Many shops offer to credit this diagnostic fee toward repair costs if you authorize the work, making the diagnosis essentially free if you proceed with recommended repairs. For a broader understanding of suspension system interactions with the steering system, our comprehensive guide on how your car’s suspension works provides valuable context.

Repair vs. Replacement Costs: What to Expect

When your rack and pinion shows signs of failure, you’ll face decisions about repair versus replacement and whether to tackle the job yourself or hire professionals. Understanding the costs involved helps you make informed choices and budget appropriately for this significant repair.

Can Rack and Pinion Be Repaired?

The question of repair versus replacement depends on the specific problem. Minor external seal leaks can sometimes be repaired by replacing the rack boots and seals without removing the rack from the vehicle. This repair option works when the leak comes from external seals rather than internal rack damage. Some shops offer this service for $200 to $400 including parts and labor, making it an economical option when applicable.

However, internal rack damage—worn gear teeth, scored rack surface, damaged internal seals, or bent housing—generally requires complete rack replacement rather than repair. While specialty shops can rebuild rack assemblies, the labor intensity of this process often costs as much or more than installing a remanufactured unit. Remanufactured racks come with warranties, have been thoroughly tested, and include new internal components, making them a better value than attempting to rebuild a high-mileage rack with unknown internal condition.

The industry has largely moved away from rebuilding rack assemblies in favor of replacement with remanufactured units. This shift reflects both economics and reliability—why spend similar money for a rebuild of questionable quality when a factory-remanufactured unit with warranty offers better value?

Detailed Replacement Cost Breakdown

Replacement costs vary significantly based on vehicle make, model, and year, but understanding the typical cost structure helps set realistic expectations. Parts costs represent the first major component. Remanufactured racks—the most common choice—typically cost $250 to $600 for standard passenger vehicles. These units have been professionally rebuilt with new internal components, tested for proper operation, and backed by warranties ranging from one to three years or longer.

New aftermarket racks cost more, typically $400 to $800, offering new rather than remanufactured components. Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) racks from the vehicle manufacturer command premium pricing, usually $600 to $1,500 or higher, justified by perfect fit and finish but offering no functional advantage over quality remanufactured units for most applications. Luxury and performance vehicles face higher parts costs, with some exotic racks exceeding $2,000 just for the part.

Labor costs typically exceed parts costs for this repair. Standard passenger vehicles require 3 to 6 hours of labor for rack replacement, translating to $300 to $900 based on typical shop rates of $75 to $150 per hour. The wide time range reflects variation in vehicle complexity. Some vehicles allow relatively straightforward rack access, while others require lowering the front subframe—a significant undertaking that supports the engine from above while technicians unbolt and lower the subframe enough to slide the rack out.

Front-wheel-drive vehicles generally require more labor than rear-wheel-drive vehicles due to packaging constraints. The transverse engine placement leaves minimal working room around the rack. All-wheel-drive vehicles can be more complex still, with additional driveline components restricting access. Geographic location affects labor rates significantly—shops in high cost-of-living areas charge more than rural locations, but this often reflects higher operating costs rather than padding.

Additional required services add to the total cost. Wheel alignment is mandatory after rack replacement, typically costing $50 to $150 depending on whether just a front alignment or complete four-wheel alignment is needed. Many shops include alignment in their quoted rack replacement price, but always verify this rather than assuming.

Outer tie rod ends often require replacement during rack installation. While inner tie rods typically come with remanufactured racks, the outer ends are separate components that attach to the steering knuckles. These outer ends may be worn or damaged, and since the rack is already out and alignment will be needed anyway, replacing worn outer tie rods makes sense. Budget $40 to $100 per side for outer tie rod ends.

Power steering fluid and any necessary hoses add modest costs—typically $20 to $40 for fluid and $50 to $150 for hoses if they’re leaking or damaged during removal. Some mechanics recommend replacing power steering hoses preventively during rack replacement on high-mileage vehicles, reasoning that the hoses are already exposed and accessible.

Real-World Total Costs by Vehicle Type

For a typical mid-size sedan like a Honda Accord or Toyota Camry, expect total rack replacement costs between $1,000 and $1,500 including parts, labor, alignment, and incidentals. Compact cars may cost slightly less at $900 to $1,300, while SUVs and trucks typically range from $1,200 to $1,800 due to larger racks and more labor-intensive installation.

Luxury vehicles command premium pricing. A rack replacement on a BMW, Mercedes-Benz, or Audi might total $2,000 to $3,000 or higher. These vehicles often use more expensive racks, require more labor due to complex packaging, and have higher shop rates at specialty import shops qualified to work on them. Performance vehicles and sports cars follow similar patterns.

At the extreme end, exotic vehicles can exceed $4,000 for rack replacement. A Porsche 911 or high-end Range Rover might require specialized racks costing $3,000+ for parts alone, plus premium labor rates at specialty shops. These represent outliers, but they underscore the importance of getting specific quotes for your particular vehicle.

Cost-Saving Strategies That Make Sense

Several legitimate approaches can reduce rack replacement costs without compromising quality or safety. Choosing a quality remanufactured rack rather than OEM new saves 30 to 50% on parts cost with no functional penalty. Major remanufacturers like Cardone, BBB Industries, and Maval Remanufacturing produce racks that meet or exceed OEM specifications, include new wear items, and carry solid warranties. Unless you’re restoring a collectible vehicle where originality matters, remanufactured racks offer excellent value.

Shopping multiple repair facilities often reveals significant price variations. Independent shops frequently cost less than dealerships for this repair while providing equal quality work. Get quotes from at least three shops, ensuring each quote includes alignment and specifies whether OEM or remanufactured parts will be used. Ask about warranty coverage—some shops include labor warranty beyond the parts warranty period.

DIY installation is possible for experienced mechanics with proper tools and workspace, potentially saving $500 to $1,000 in labor costs. However, this job exceeds beginner DIY skill levels. You’ll need a lift or quality jack stands, metric socket set, torque wrench, pickle fork or ball joint separator, rack centering tools for electric racks, and ability to bleed hydraulic systems if applicable. Most critically, you’ll still need professional alignment afterward.

The safety-critical nature of steering makes this a poor choice for learning or experimenting. If you have the skills, tools, and confidence, DIY installation can save substantially. If any of those elements are missing, professional installation is the responsible choice. Remember that improper installation can result in steering failure, component separation, or other dangerous malfunctions.

Preventive Maintenance as the Best Cost Saving

The most effective cost-saving strategy is preventive maintenance that extends rack life and delays or prevents replacement entirely. Regular power steering fluid changes every 50,000 to 75,000 miles keep hydraulic systems operating smoothly and prevent abrasive contaminated fluid from wearing precision surfaces. This simple service costs $100 to $150 but can add years of life to the rack.

Annual boot inspection catches tears before they allow contamination entry. Replacing torn boots early—a $50 to $150 service—prevents the expensive internal damage that necessitates complete rack replacement. Addressing small leaks promptly prevents the running-dry scenario that damages pumps and racks simultaneously, turning a modest repair into a major expense.

Avoiding curb impacts and potholes when possible reduces shock loads on the rack. While you can’t avoid all road hazards, consciously steering around obvious potholes and being careful when parking near curbs reduces impact-related damage. These driving habits cost nothing but can significantly extend component life.

Maintenance and Longevity: Maximizing Rack Life

Proper maintenance significantly extends rack and pinion system life while improving reliability and performance. Understanding the service intervals and best practices helps you avoid premature failure and expensive repairs.

Establishing a Routine Maintenance Schedule

For hydraulic power steering systems, fluid inspection should occur every 30,000 to 50,000 miles or during every other oil change. Check fluid level and examine its color and clarity. The fluid should appear pink or red and translucent. Dark, cloudy, or black fluid indicates overdue for change. Low fluid level suggests a leak that requires investigation and correction.

Complete power steering fluid flush and replacement should occur every 50,000 to 75,000 miles depending on manufacturer recommendations and driving conditions. This service removes contaminated fluid, replacing it with fresh fluid that provides proper lubrication and corrosion protection. The cost of $100 to $150 represents excellent value considering it can prevent a $1,500 rack replacement.

Rack boot inspection deserves annual attention, particularly if you drive in harsh conditions with salt exposure, off-road use, or heavy urban driving with curb parking. Look for tears, cracks, or deterioration in the rubber or synthetic boot material. Feel the boots to verify they contain grease and aren’t loose or empty. Any boot damage warrants immediate replacement before contaminants enter the rack housing.

Tie rod end inspection should occur during routine maintenance intervals around 50,000 to 75,000 miles or whenever you hear clunking noises from the front end. While the tie rods aren’t part of the rack assembly itself, worn tie rod ends affect steering response and can damage the rack if they fail completely. Our guide on inner tie rod end diagnosis and replacement provides detailed information on checking these critical components.

Best Practices for Extended System Life

Fluid maintenance represents the single most important factor in rack longevity for hydraulic systems. Always use the manufacturer-specified power steering fluid type. Despite marketing claims, “universal” power steering fluids don’t exist—different manufacturers require different fluid formulations, and using incorrect fluid damages seals, reduces lubrication effectiveness, and shortens component life.

Never mix different fluid types. If you’re uncertain what fluid is currently in the system, have the entire system flushed and filled with the correct fluid. Keep the fluid reservoir topped up between service intervals—running low on fluid allows air into the system and reduces lubrication protection. Address leaks promptly rather than continuously adding fluid, as the leak will worsen and the underlying problem will cause more damage.

Driving habits influence rack life more than most people realize. Avoid hitting curbs and potholes when possible—these impacts transmit shock loads directly through the tie rods into the rack, potentially bending the housing or damaging internal components. Be especially careful during winter when snow banks can hide curbs, and in urban areas where potholes proliferate.

Don’t hold the steering wheel at full lock (turned completely left or right) for extended periods, particularly at idle. This practice maximizes pressure in hydraulic systems and stress on electric motors, generating unnecessary heat and wear. Turn the wheel just until the tires reach their stop, then ease off slightly. During parking maneuvers, minimize the time spent at full lock.

Turn the steering wheel while the vehicle is moving rather than stationary when possible. Static steering—turning the wheels while the vehicle isn’t moving—maximizes the effort required and stress on components. If you must turn the wheels while stopped, such as when parallel parking, the engine should be running to provide full power assist.

For hydraulic systems specifically, regular engine warm-up in winter allows the power steering fluid to reach operating temperature. Cold, thick fluid doesn’t flow properly and forces the pump to work harder, creating excess wear. While modern vehicles don’t require lengthy warm-up periods, giving the engine and fluid a minute or two to warm up before making hard steering inputs helps component longevity.

Keep the power steering system clean and dry. While rack boots protect the rack itself, accumulated road salt, oil, and grime on external components promotes corrosion of fittings, brackets, and housings. Periodic undercarriage cleaning, particularly after winter driving in salt-belt regions, removes corrosive materials before they cause damage.

Expected Lifespan and Replacement Planning

Under normal conditions with proper maintenance, a rack and pinion assembly should last 100,000 to 150,000 miles. Many vehicles exceed these figures—200,000+ mile racks aren’t uncommon with excellent maintenance and highway-heavy driving patterns. However, severe service conditions—heavy city driving, lots of curb parking, road salt exposure, extreme temperatures—can reduce life expectancy to 80,000 miles or less.

Driving pattern significantly affects longevity. Highway miles involve relatively few steering inputs compared to the constant turning required in urban and suburban driving. A vehicle with 150,000 mostly highway miles might have a rack in better condition than an urban delivery vehicle with 80,000 hard miles. This explains why trucks and commercial vehicles often need rack replacement sooner than passenger cars despite lower mileage.

Once your vehicle accumulates 100,000 miles or approaches 10 years of age, budget for eventual rack replacement as preventive financial planning. While the rack might last considerably longer, having the funds available prevents financial stress if replacement becomes necessary. This planning also allows you to be selective about repair timing rather than accepting the first shop you can afford.

Watch for early warning signs that allow you to schedule replacement at your convenience rather than facing an emergency repair. Slight increase in steering effort, minor play development, or small fluid seepage often precede complete failure by months or even years. Addressing these symptoms proactively gives you time to shop for quotes, save money, and schedule the repair when convenient.

Rack and Pinion vs. Recirculating Ball Steering

Understanding the alternative to rack and pinion steering helps explain why this system has achieved market dominance and what trade-offs exist between the two technologies.

Why the Comparison Matters

Before rack and pinion became standard, recirculating ball steering dominated the automotive industry for decades. This older technology used a worm gear meshing with a sector gear, with ball bearings recirculating through the gears to reduce friction. The system required more components—a steering box housing the gears, a pitman arm, an idler arm, and center link connecting everything—creating a more complex mechanical arrangement.

Many trucks, particularly heavy-duty models and those with solid front axles, continue using recirculating ball steering. Understanding the differences helps when evaluating used vehicles or deciding between truck models that may offer either system.

Key Advantages of Rack and Pinion

The simplicity advantage is substantial. Rack and pinion systems use two main gears and direct tie rod connections, while recirculating ball requires the gearbox plus multiple linkage components. Fewer parts mean fewer potential failure points, lower manufacturing costs, and typically higher long-term reliability. The rack and pinion design creates only four wear points in the linkage—the two inner tie rod connections and two outer tie rod ends—compared to six or more wear points in a recirculating ball system.

Weight savings contribute to better handling and fuel economy. The compact rack and pinion assembly weighs significantly less than a recirculating ball gearbox, heavy pitman arm, idler arm, and center link. This weight reduction comes off the front of the vehicle where it has the greatest impact on handling dynamics. Less weight allows the suspension to respond more quickly to road irregularities and reduces rotational inertia during turns.

Steering feel and precision represent perhaps the most significant advantages. The direct mechanical connection from steering wheel through the rack to the wheels provides immediate, proportional response. Every input translates directly to wheel movement without the compliance and slack inherent in multiple linkage connections. This direct feel explains why virtually all performance vehicles use rack and pinion steering.

Packaging flexibility makes rack and pinion ideal for modern vehicle designs, particularly front-wheel-drive platforms where the transverse engine placement leaves limited space for steering components. The tubular rack housing fits into tighter spaces than a recirculating ball gearbox and its associated linkage.

When Recirculating Ball Makes Sense

Heavy-duty applications still favor recirculating ball in some cases. The gearbox design provides greater mechanical advantage, making it easier to turn large, heavy tires—important for trucks that might use 35-inch or larger off-road tires. The robust gearbox housing can withstand the substantial forces involved in extreme four-wheel-drive use.

Solid front axle vehicles—primarily heavy-duty trucks and serious off-road vehicles—work better with recirculating ball steering in some applications. The centerlink arrangement accommodates the axle’s lateral movement more easily than rack and pinion systems. However, even this advantage has diminished as manufacturers develop rack and pinion systems suitable for solid axle applications.

Greater steering travel is available from recirculating ball systems by varying the pitman arm length, useful in some specialized applications. However, for passenger vehicles and light trucks, the travel provided by rack and pinion systems is entirely adequate.

Industry Evolution and Current Trends

The industry trend decisively favors rack and pinion steering. Over 85% of new vehicles now use rack and pinion systems, with the percentage increasing annually. Even heavy-duty trucks increasingly adopt rack and pinion designs as manufacturers develop systems robust enough for these applications while maintaining the precision, weight savings, and simplicity advantages.

Recirculating ball steering persists mainly in specialized heavy-duty trucks, some full-size pickups (particularly those designed for extreme towing or off-road use), and vehicles with solid front axles where the suspension geometry better suits this steering arrangement. As independent front suspension becomes more common even on trucks, rack and pinion systems follow.

For most drivers, rack and pinion steering delivers the optimal combination of precision, reliability, and low maintenance requirements. The technology has proven itself over 50+ years of continuous refinement, and ongoing developments in electric power steering continue to enhance its capabilities.

Conclusion

The rack and pinion steering system represents automotive engineering at its finest—a elegantly simple mechanical solution that converts your steering input into precise wheel control through nothing more complicated than two gears working in harmony. From its basic mechanical principle of translating rotational motion to linear movement, to the sophisticated hydraulic and electric assist systems that make modern steering effortless, this technology has transformed how we control our vehicles.

Understanding how your rack and pinion system works empowers you to recognize problems early, make informed maintenance decisions, and appreciate the engineering that makes modern driving safe and enjoyable. The warning signs we’ve discussed—steering difficulty, unusual noises, fluid leaks, loose steering response—provide early indication of problems before they compromise safety or lead to expensive failures. Paying attention to these symptoms and addressing them promptly protects both your vehicle and your family’s safety.

Regular maintenance, particularly proper power steering fluid care in hydraulic systems and attention to rack boot condition, can extend your system’s life well beyond 100,000 miles. The preventive approach—inspecting boots annually, changing fluid on schedule, avoiding curb impacts—costs far less than premature rack replacement and provides peace of mind knowing your steering system operates reliably.

When problems do arise, professional diagnosis and service represent the responsible choice for this safety-critical system. While basic inspections are DIY-friendly for intermediate mechanics, the complexity of modern vehicles and the critical nature of steering control make expert service essential for major work. The cost of professional rack and pinion replacement—typically $1,000 to $2,000 for standard vehicles—reflects the labor intensity and precision required to ensure safe, proper operation. Related suspension components also require periodic attention, and our guides on how control arm bushings work and how MacPherson strut suspension works provide additional context for maintaining your complete steering and suspension system.

Whether your vehicle uses hydraulic or electric power steering, understanding the technology helps you maintain it properly and recognize when service is needed. The industry’s shift toward electric power steering reflects ongoing refinement and improvement, but both systems share the fundamental rack and pinion mechanism that has served reliably for decades.

Make rack and pinion inspection part of your regular vehicle maintenance routine. During oil changes and tire rotations, take a moment to check for fluid leaks, inspect boot condition, and note any changes in steering feel or response. This proactive approach catches small problems before they become major expenses and keeps your steering system operating as intended—providing the precise, responsive control that modern drivers expect and deserve. For comprehensive information on how the complete suspension system works with your steering, our article on how shock absorbers and struts work offers valuable insights into these complementary systems that work together to provide safe, controlled vehicle operation.