Have you ever hit a pothole and felt your car smoothly recover, or watched another vehicle continue bouncing like a pogo stick? That difference comes down to one critical component: shock absorbers. These unassuming cylindrical devices play a dual role that most drivers underestimate—they’re not just about comfort, they’re essential safety equipment that directly affects your ability to control your vehicle and stop safely.

Shock absorbers are hydraulic or gas-charged damping devices designed to control suspension movement and keep your tires firmly planted on the road. Despite their name, shock absorbers don’t actually absorb shocks—that’s the job of your suspension springs. Instead, shocks dampen the oscillations that springs create, preventing your car from bouncing uncontrollably after every bump. This damping action is what separates a controlled, safe ride from a dangerous, unpredictable one.

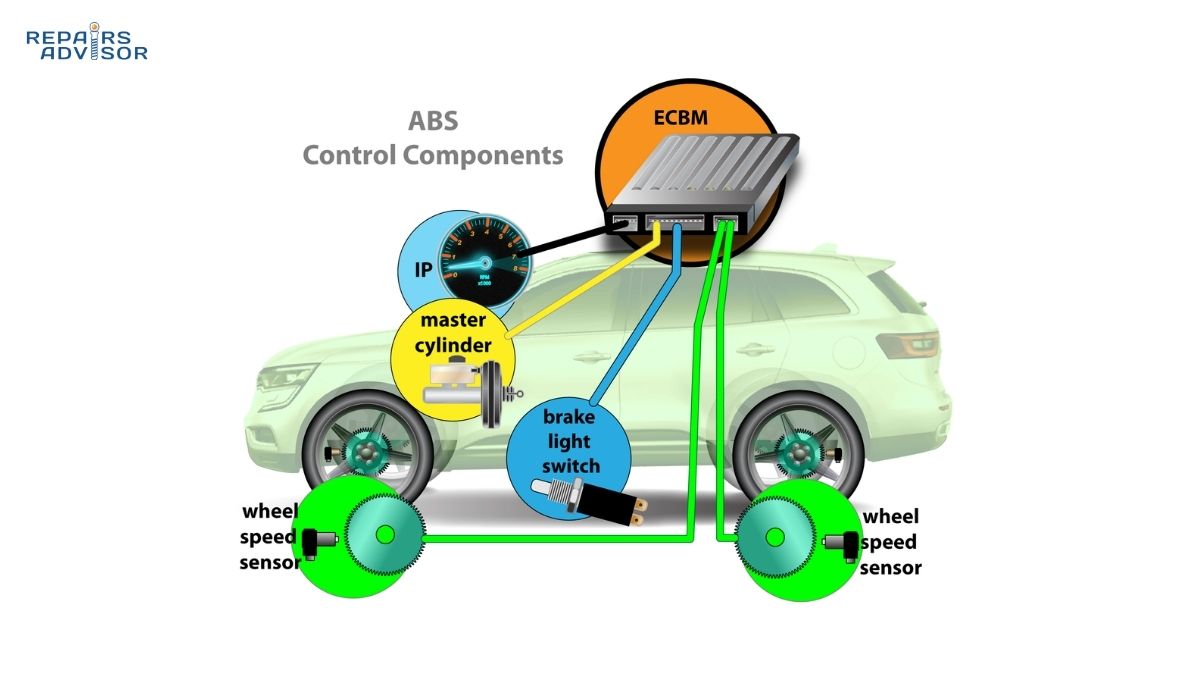

Modern vehicles use several shock absorber types, including conventional telescopic shocks, strut-type assemblies, twin-tube designs, and mono-tube configurations. Each serves the same fundamental purpose: converting kinetic energy (motion) into thermal energy (heat) through hydraulic resistance. When working properly, shocks maintain tire contact with the road surface, control weight transfer during braking and acceleration, reduce body roll in corners, and provide the stable platform necessary for your vehicle’s safety systems like ABS and stability control to function effectively.

The consequences of worn shock absorbers are severe and immediate. Studies show that worn shocks can increase braking distance by up to 20 percent—the difference between stopping safely and causing an accident. They also accelerate tire wear, compromise handling stability, and reduce the effectiveness of your vehicle’s electronic safety systems. With typical lifespans ranging from 50,000 to 100,000 miles depending on driving conditions, shock absorbers are maintenance items that require regular inspection and timely replacement.

Understanding how shock absorbers work helps you recognize when they’re failing and why professional replacement is often necessary, especially for strut-type designs that involve compressed springs under extreme tension.

Important Safety Note: While shock absorber inspection is DIY-friendly, replacement requires proper vehicle support, specialized tools, and technical knowledge. Worn shocks significantly affect braking distance (up to 20% longer), handling, and tire wear. If you notice symptoms of worn shocks—excessive bouncing, nose diving during braking, or fluid leaks—have your vehicle inspected by a qualified technician immediately. Never attempt strut replacement without proper spring compressor equipment and training, as compressed springs contain over 1,000 pounds of force and can cause catastrophic injury if released improperly.

What Are Shock Absorbers? Parts and Types Explained

A shock absorber is a hydraulic or pneumatic damping device that controls the oscillation of suspension springs and manages the vertical movement of your vehicle’s wheels. The terminology can be confusing—while commonly called “shock absorbers,” these components are more accurately described as “dampers” because their primary function is damping spring motion rather than absorbing impacts. This distinction is important: springs absorb the initial shock from road irregularities, while dampers control how quickly the springs compress and extend, preventing continuous bouncing.

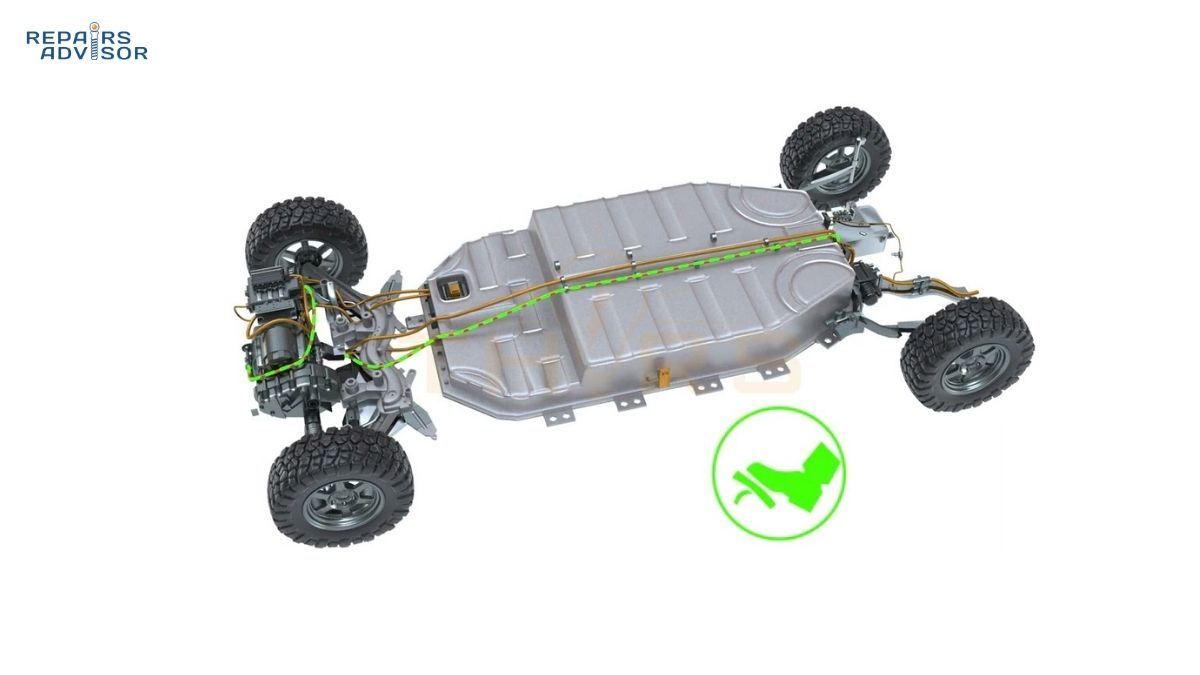

The fundamental purpose of shock absorbers extends beyond passenger comfort. These components serve critical safety functions by maintaining consistent tire contact with the road surface, controlling weight transfer during braking and acceleration, managing body roll during cornering, and providing the stable platform necessary for modern electronic safety systems to function. When your ABS system pulses the brakes to prevent wheel lockup, it depends on shock absorbers maintaining tire contact. When electronic stability control applies individual brakes to correct a skid, worn shocks compromise its effectiveness.

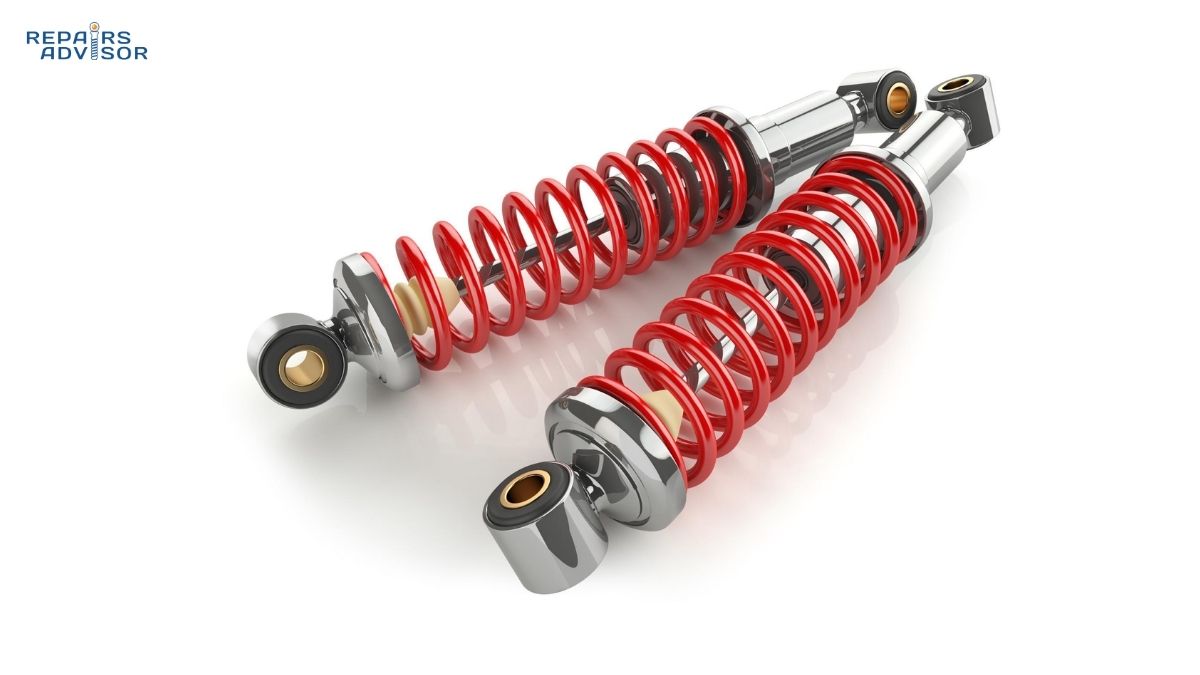

Basic Components: Inside a Telescopic Shock Absorber

The most common shock absorber design—the telescopic shock—consists of several precisely engineered components working together to create controlled hydraulic resistance. Understanding these parts helps clarify how shocks function and why they eventually wear out.

The outer tube, also called the reserve tube in twin-tube designs, serves as the shock’s main housing and contains the hydraulic fluid reservoir. This tube must withstand constant vibration, temperature extremes, and exposure to road salt and debris. Quality shocks feature corrosion-resistant coatings—powder coating or electroplating—that protect the outer tube from rust and environmental damage. Budget shocks often use simple paint that deteriorates quickly, leading to corrosion and premature failure.

The inner tube, or pressure tube, houses the piston and serves as the working cylinder where hydraulic damping occurs. In twin-tube designs, this smaller diameter tube sits inside the reserve tube and contains the high-pressure hydraulic action. The precision machining of this cylinder is critical—surface roughness affects seal life and damping consistency. Premium manufacturers like Bilstein and KYB maintain tolerances within 0.001 inches, while budget shocks may have rougher bore surfaces that accelerate wear.

The piston attaches to the piston rod and moves up and down through the hydraulic fluid, creating the resistance that dampens suspension movement. Modern pistons contain sophisticated valve systems with multiple orifices (small holes) that control fluid flow. The size, number, and arrangement of these orifices determine the shock’s damping characteristics. Performance shocks often feature adjustable pistons that allow you to modify damping rates by changing valve configurations.

Piston valve systems represent the most complex aspect of shock absorber design. These valves use thin metal discs called shims stacked in precise arrangements to control fluid flow through the piston orifices. During compression, specific valves open to allow fluid passage at controlled rates. During rebound (extension), different valves control the return stroke. The thickness, diameter, and number of shim discs determine damping rates—professional race teams spend countless hours tuning these valve stacks to optimize performance for specific tracks and conditions.

The piston rod connects the piston to the vehicle’s chassis or suspension components. This hardened steel shaft must resist bending forces while maintaining a precisely smooth surface for the seal to work effectively. Chrome plating protects the rod from corrosion and reduces friction. Any damage to the rod surface—pitting, scratches, or bends—allows fluid leakage and compromises shock performance. This is why bent piston rods from accident damage require complete shock replacement rather than repair.

Seals and guides prevent hydraulic fluid from escaping while guiding the piston rod’s movement. The primary seal uses a square-section rubber O-ring that sits in a groove in the shock body. This seal serves dual purposes: preventing fluid leaks and providing the mechanism for piston retraction when pressure releases. Quality seals use fluoroelastomer or polyurethane materials that resist degradation at temperatures exceeding 400°F. Budget seals made from standard rubber compounds deteriorate quickly under heat, leading to leaks within 2-3 years.

Mounting hardware—bushings, bolts, and rubber isolators—connects the shock to the vehicle’s chassis and suspension. These rubber bushings provide vibration isolation while allowing the necessary movement. Worn mounting bushings create clunking noises and reduce shock effectiveness even if the shock itself remains functional. When replacing shocks, always inspect and replace worn mounting hardware.

Gas chambers in gas-charged shocks contain pressurized nitrogen (typically 100-360 PSI) that prevents cavitation—the formation of vapor bubbles that causes inconsistent damping and fade. The nitrogen pressure maintains solid hydraulic fluid throughout the stroke, even during rapid piston movement. This gas charge also provides a small amount of spring assistance, slightly raising the vehicle. Gas charging technology significantly improves shock performance and consistency, which is why most modern shocks use this design.

Twin-Tube Design: The Industry Standard

Twin-tube shock absorbers dominate the automotive market, appearing on 60-70 percent of passenger vehicles due to their cost-effectiveness, compact design, and reliable performance for normal driving conditions. This design uses two nested cylindrical tubes: an inner working tube (pressure tube) where the piston operates, and an outer reserve tube that contains additional hydraulic fluid and serves as a reservoir.

During operation, the piston moves through the pressure tube, forcing fluid through the piston valves. Additionally, fluid flows between the pressure tube and reserve tube through a base valve at the bottom of the shock. This base valve provides secondary damping control and allows the shock to accommodate the volume change as the piston rod enters and exits the pressure tube. The reserve chamber also provides space for thermal expansion and helps dissipate heat, though less effectively than mono-tube designs.

The advantages of twin-tube construction include lower manufacturing costs compared to mono-tube designs, more compact dimensions allowing easier packaging in tight suspension spaces, tolerance for various mounting angles including horizontal mounting, and proven reliability for everyday driving conditions. These factors make twin-tube shocks the economical choice for most passenger cars and light SUVs where extreme performance isn’t required.

However, twin-tube designs have limitations under severe conditions. The reserve tube’s fluid can aerate (mix with air) during rapid suspension movement, creating foam that reduces damping effectiveness—a condition called fade. Heat dissipation is also less efficient due to the smaller surface area of the inner working tube and the insulating effect of the reserve chamber. For these reasons, performance vehicles and heavy-duty applications often specify mono-tube designs instead. Twin-tube shocks work well in common MacPherson strut suspension configurations found on most modern cars.

Mono-Tube Design: Performance and Heavy-Duty Applications

Mono-tube shock absorbers use a single pressure tube containing two pistons: a working piston attached to the piston rod, and a floating piston that separates the hydraulic fluid from a high-pressure nitrogen gas chamber. This gas pressure typically ranges from 200 to 360 PSI—much higher than twin-tube designs—and prevents cavitation while maintaining consistent hydraulic pressure throughout the stroke range.

The working piston operates similar to twin-tube designs, moving through hydraulic fluid and forcing it through valves to create damping. However, because there’s only one tube, the shock must accommodate volume changes from the piston rod differently. As the rod enters the tube during compression, it displaces fluid volume. The floating piston moves to compress the gas chamber, accommodating this volume change while maintaining constant hydraulic pressure. During extension, the gas pressure pushes the floating piston back, maintaining proper fluid pressure.

Mono-tube advantages include superior heat dissipation because the working cylinder directly contacts the outer tube with maximum surface area exposed to cooling air, more consistent performance under sustained hard use since there’s no aeration or fade from reserve chamber turbulence, larger piston diameter (typically 40-46mm vs. 30-36mm in twin-tubes) allowing greater fluid displacement and more effective damping, and the ability to mount the shock in any position including upside-down since there’s no base valve requiring proper orientation.

These performance benefits come with trade-offs: mono-tube shocks cost 30-50 percent more than equivalent twin-tube designs, require larger diameter bodies that may not package well in compact suspension spaces, are sensitive to external damage since the working cylinder is the outer tube (any dent affects piston operation), and cannot typically be mounted horizontally due to potential gas and fluid separation issues.

Mono-tube designs excel in performance vehicles, heavy trucks, SUVs used for towing, and off-road applications where consistent damping under extreme conditions justifies the higher cost. Professional racing applications almost exclusively use mono-tube designs due to their superior heat management and performance consistency.

Strut-Type Shock Absorbers: Structural Suspension Components

Strut-type shock absorbers combine a conventional shock absorber with a structural suspension member, creating a single assembly that provides both damping and spring support while forming part of the steering system on front suspensions. The MacPherson strut—the most common strut design—dominates modern front suspension applications, appearing on approximately 70 percent of passenger cars worldwide due to its compact design and cost-effectiveness.

Unlike conventional shocks that only provide damping, struts must handle multiple functions simultaneously: damping suspension oscillations like a standard shock, supporting the vehicle’s weight through the coil spring that surrounds the strut, providing a mounting point for the steering knuckle and upper suspension attachment, and maintaining precise suspension geometry for proper wheel alignment. This multi-functional design requires much more robust construction than conventional shocks.

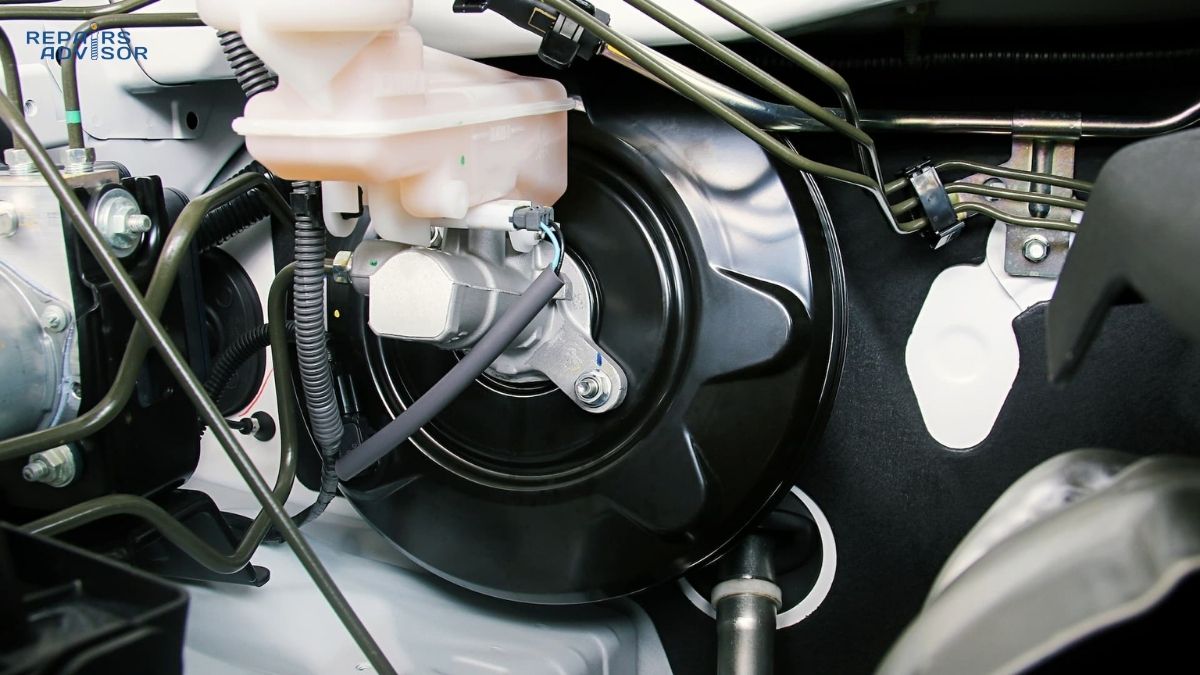

The strut assembly consists of a strengthened shock absorber body that can handle structural loads, a coil spring seated on the strut body, upper strut mount containing a bearing that allows steering rotation, lower mounting bracket that bolts to the steering knuckle, and the shock absorber cartridge (the actual damping mechanism) inside the strut body. Some designs allow cartridge replacement while others require complete assembly replacement.

Strut replacement presents significant safety concerns that conventional shock replacement does not. The coil spring surrounding the strut remains under extreme compression—typically 1,000 to 1,500 pounds of force—even when the vehicle is raised and the suspension hangs free. Removing the strut without proper spring compression exposes you to catastrophic spring release that can cause severe injury or death. Professional technicians use hydraulic spring compressors designed specifically for this task, with safety cages and redundant locking mechanisms.

Many technicians and DIY mechanics now opt for complete strut assemblies (often called “quick struts”) that come pre-assembled with a new strut, spring, mount, and hardware. These assemblies cost more in parts but eliminate the dangerous spring compression procedure, reduce installation time by 50-70 percent, and ensure all components are new rather than reusing a potentially worn spring or mount. The additional $50-$100 per strut for complete assemblies is money well spent for safety and reliability.

Modern strut designs also integrate other components: ABS wheel speed sensors often mount to the strut body, brake hoses may route along the strut, steering knuckle attachment requires precise alignment, and electronic adaptive damping sensors (on vehicles so equipped) connect to the strut. This integration means strut replacement requires careful attention to these ancillary components and often necessitates wheel alignment after installation since strut replacement can alter suspension geometry.

Hydraulic Fluid: The Critical Working Medium

The hydraulic fluid inside shock absorbers must perform under extreme and varying conditions: temperature ranges from -40°F in winter cold starts to over 400°F during sustained hard driving, rapid pressure changes during high-speed compression and rebound cycles, constant shearing forces that can break down fluid molecules, exposure to moisture infiltration through seals, and chemical compatibility with seals, metal components, and gas charges. These demanding requirements necessitate specially formulated fluids rather than standard hydraulic oils.

Quality shock absorber fluid contains several critical additives: viscosity modifiers maintain consistent damping across temperature ranges, preventing the fluid from becoming too thin when hot or too thick when cold; anti-foaming agents prevent aeration that causes cavitation and inconsistent damping; anti-wear additives protect cylinder and piston surfaces from metal-to-metal contact; oxidation inhibitors prevent fluid breakdown from heat and oxygen exposure; and corrosion inhibitors protect internal steel components from rust.

The viscosity index—how much the fluid’s thickness changes with temperature—is perhaps the fluid’s most critical property. During cold weather operation, especially at startup, shock fluid must remain thin enough to flow through small piston orifices and provide proper damping. If fluid becomes too thick, the shock feels harsh and unresponsive. During hot operation, particularly after sustained highway driving or mountain descents, the fluid must maintain sufficient viscosity to provide damping force. If it becomes too thin, damping effectiveness drops dramatically—a condition called fade.

Modern synthetic shock fluids offer superior performance compared to older mineral-based formulations. Synthetic fluids maintain more consistent viscosity across wider temperature ranges, resist oxidation better for longer service life, have lower pour points for better cold-weather operation, and provide superior lubrication to extend seal and component life. Premium shock manufacturers like Bilstein and Öhlins use proprietary synthetic formulations developed specifically for their products.

Most modern shocks are sealed for life—the manufacturer fills them with fluid during production and seals them permanently. This design prevents contamination, moisture entry, and the need for maintenance. However, it also means that fluid degradation, leakage, or contamination requires complete shock replacement. Older shock designs featured replaceable cartridges or rebuild capability, but modern economics favor complete replacement over rebuilding for most applications.

Gas Charging: Preventing Cavitation and Fade

Gas-charged shock absorbers use pressurized nitrogen gas to maintain solid hydraulic fluid throughout the entire stroke range, preventing a phenomenon called cavitation that severely degrades damping performance. Understanding cavitation and how gas charging prevents it reveals why modern high-performance shocks universally adopt this technology.

Cavitation occurs when hydraulic fluid pressure drops below the fluid’s vapor pressure, causing dissolved gases and moisture to form bubbles. During rapid piston movement—like hitting a sharp bump at highway speed—the fluid on the suction side of the piston experiences extremely low pressure. If this pressure drops sufficiently, vapor bubbles form in the fluid. These compressible gas bubbles eliminate the solid hydraulic column necessary for effective damping. When the piston suddenly encounters compressible vapor instead of incompressible fluid, damping force drops to nearly zero—the shock “bottoms out” with no resistance.

The effects of cavitation are immediate and dangerous: inconsistent damping with harsh impact feel followed by no damping, loss of vehicle control during rapid suspension movements, accelerated internal wear as bubbles collapse against metal surfaces (cavitation erosion), overheating from energy dissipation during bubble collapse, and progressive fade as cavitation becomes more severe with continued operation.

Gas charging solves cavitation by pressurizing the entire hydraulic system above the fluid’s vapor pressure. Nitrogen gas—always nitrogen, never air—pressurizes the system to 100-360 PSI depending on shock design and application. This elevated base pressure ensures that even during the lowest-pressure portion of the stroke, fluid pressure remains above the vapor pressure threshold, preventing bubble formation.

Twin-tube gas-charged shocks use a bladder or separator between the reserve chamber fluid and nitrogen gas, pressurizing the hydraulic fluid to approximately 100-150 PSI. Mono-tube designs use the floating piston to maintain gas pressure of 200-360 PSI directly against the working fluid. This higher pressure in mono-tubes explains their superior fade resistance and consistent performance under extreme conditions.

Gas charging provides additional benefits beyond cavitation prevention: slight vehicle height increase (typically 0.25-0.75 inches) from gas pressure assistance, faster response to small suspension inputs since the system is pre-pressurized, reduced suction cavitation during rapid extension strokes, and improved damping consistency across the full stroke range. These benefits explain why gas-charged shocks have become the standard for most modern vehicles, with non-gas shocks now limited to the most basic economy applications.

The disadvantage of gas charging is slightly firmer ride quality compared to non-gas shocks due to the pre-load pressure. However, modern shock designs with sophisticated valve tuning minimize this effect, providing both excellent ride comfort and fade-resistant performance.

How Shock Absorbers Work: Step-by-Step Operation

The operation of a shock absorber relies on a fundamental principle of fluid dynamics: forcing liquid through small openings creates resistance proportional to the fluid’s velocity. Think of moving your hand slowly through water versus rapidly—slow movement encounters gentle resistance, while rapid movement faces dramatically increased force. Shock absorbers exploit this velocity-dependent resistance to control suspension movement smoothly and proportionally.

Understanding this velocity-sensitive damping is key to appreciating shock absorber function. When your suspension moves slowly—like gradual body roll during a gentle turn—the shock provides minimal resistance, allowing smooth weight transfer and comfortable motion. When suspension moves rapidly—hitting a pothole at highway speed—the shock automatically provides much higher resistance, preventing harsh impacts and maintaining vehicle control. This automatic adjustment happens purely through hydraulic principles without any electronics or moving parts in traditional shocks.

The energy transformation taking place is equally important. When your wheel hits a bump, the impact energy becomes kinetic energy in the suspension movement. The springs absorb this energy by compressing, temporarily storing it as potential energy. When the springs extend, they release this stored energy. Without damping, this energy would cause continuous bouncing—the springs would oscillate until friction eventually dissipated the energy. Shock absorbers rapidly convert this kinetic energy into thermal energy through hydraulic friction, stopping the oscillation within 1-2 cycles and preventing bounce.

Compression Stroke: Absorbing Impact Energy

The compression stroke—also called the jounce or bump phase—occurs when the wheel encounters an upward displacement like a bump, pothole, or expansion joint. This upward wheel movement compresses the suspension spring and forces the shock absorber piston deeper into the cylinder. Understanding what happens during this critical phase reveals how shocks manage impact forces while maintaining ride comfort.

As the suspension compresses, the shock piston rod moves downward (on a typical shock mounted with the piston rod up), pushing the piston deeper into the hydraulic fluid-filled cylinder. This piston movement must displace the fluid in front of it, but the fluid has nowhere to go except through small orifices (holes) in the piston itself and through valves controlling flow rate. The size of these orifices and the valve settings determine compression damping characteristics.

During slow compression—like loading cargo into your vehicle or a gentle dip in the road—fluid flows relatively easily through the compression valves. The valves open at low pressures, allowing smooth, comfortable motion without harsh resistance. This is intentional design: compression damping is typically set softer than rebound damping because you want the wheel to follow road contours and absorb impacts without transmitting harsh jolts to the vehicle body and passengers.

During rapid compression—hitting a pothole or speed bump at higher speeds—the much higher fluid velocity creates dramatically increased pressure against the piston valves. However, shock engineers design these valves to open progressively, preventing excessive harshness while still controlling motion. The valve system uses stacked metal shims (thin discs) that flex open under pressure, allowing increased flow as pressure rises. This creates progressive damping: gentle resistance for small, slow inputs and firm control for large, rapid inputs.

Modern performance shocks feature separate low-speed and high-speed compression circuits. Low-speed compression damping (typically 0-1.5 inches per second) controls body motions like weight transfer, dive, and squat. High-speed compression damping (above 1.5 inches per second) controls impact harshness from bumps and holes. Some adjustable shocks allow independent adjustment of these circuits, letting you soften ride quality without compromising control or vice versa.

The compression stroke also involves volume compensation. As the piston rod enters the cylinder, it displaces a volume of fluid equal to the rod’s cross-sectional area times its travel distance. In twin-tube designs, this excess fluid flows through the base valve into the reserve chamber. In mono-tube designs, the floating piston moves to compress the gas chamber, accommodating the rod volume. This volume displacement is why shocks need reserve capacity and why damage to the outer tube (in mono-tubes) or base valve (in twin-tubes) causes immediate shock failure.

Throughout compression, the shock generates heat as hydraulic friction converts motion energy into thermal energy. This heat must dissipate through the shock body or fluid capacity becomes overwhelmed, causing fluid to thin and damping to fade. Quality shocks use larger fluid capacity and better heat-dissipating designs to maintain performance during sustained hard use—critical for vehicles descending mountain grades, towing heavy loads, or track driving.

Rebound Stroke: Controlling Spring Extension

The rebound stroke—also called extension or droop—occurs as the compressed spring extends back to its neutral position after absorbing an impact. While compression damping gets more attention, rebound damping is actually more critical for vehicle control, handling, and safety. Understanding why rebound control matters reveals how shock absorbers maintain stability and tire contact.

When the spring compresses and then releases, it stores and returns energy efficiently. Without rebound damping, the spring would extend violently, throwing the wheel downward with considerable force. This rapid extension would cause the wheel to leave the ground momentarily, eliminating steering and braking control. The shock’s rebound damping prevents this by controlling how quickly the spring can extend, ensuring the wheel follows the road surface rather than bouncing off it.

As the spring extends, it pulls the shock piston rod upward (in typical mounting orientation), drawing the piston through the hydraulic fluid. Now fluid must flow in the opposite direction—from below the piston to above it—passing through different valves than those used during compression. These rebound valves are calibrated significantly firmer than compression valves because controlling extension speed is more important for safety than controlling compression speed.

Professional suspension engineers typically set rebound damping 2-3 times firmer than compression damping. This asymmetric damping serves multiple purposes: prevents wheel pogo-sticking after bumps, controls weight transfer during braking and acceleration, maintains tire contact with road surface (critical for traction), prevents body float on undulating roads, and resists nose-dive during hard braking while controlling squat during acceleration.

The velocity-sensitive nature of rebound damping means shocks automatically adjust their resistance to match conditions. During slow rebound—like a passenger exiting the vehicle—the shock allows gradual, comfortable body rise. During rapid rebound—hitting a bump that first compresses then quickly extends the suspension—the shock provides firm resistance to prevent violent extension and maintain tire contact.

Worn shock absorbers lose rebound damping first. The telltale bounce test—pushing down a corner of the vehicle and counting how many times it bounces—checks rebound damping effectiveness. A properly functioning shock should stop body motion within 1-2 bounces. If the vehicle bounces 3+ times, rebound damping has degraded severely and replacement is necessary. This worn rebound damping is what causes the characteristic “bouncy ride” of vehicles with bad shocks.

The rebound stroke also deals with the volume change as the piston rod exits the cylinder. In twin-tube designs, fluid flows from the reserve chamber back into the working cylinder through the base valve. In mono-tube designs, gas pressure pushes the floating piston back down, maintaining proper fluid volume in the working chamber. Restrictions in these passages—dirt in the base valve or a sticking floating piston—can cause asymmetric damping where the shock behaves differently in compression versus rebound.

Heat generation during rebound often exceeds compression heating because rebound damping is firmer and because rebound strokes typically occur more slowly than compression strokes (the spring controls extension rate). This sustained heat generation during highway driving or mountain descents can cause fade if the shock cannot dissipate heat adequately. Premium shocks with external reservoirs or advanced heat dissipation designs maintain consistent performance during extended hard use.

Velocity-Sensitive Damping: Automatic Adaptation

One of the most elegant aspects of hydraulic shock absorber design is velocity-sensitive damping—the shock automatically increases resistance as piston speed increases without requiring any electronic controls or moving parts. This automatic adaptation allows a single shock to provide comfortable ride quality over small, slow bumps while firmly controlling large, rapid suspension movements. Understanding how hydraulic valves achieve this reveals sophisticated engineering hidden within seemingly simple components.

The fundamental principle relies on hydraulic pressure increasing with fluid velocity. When the piston moves slowly through the hydraulic fluid, pressure differential across the piston valves remains low, and the valves open easily to allow smooth fluid flow with minimal resistance. When the piston moves rapidly, the much higher fluid velocity creates dramatically increased pressure differential, and resistance increases proportionally even though the orifice sizes haven’t changed.

Shock engineers further refine this response using valve shim stacks—thin metal discs stacked in precise arrangements on the piston face. During gentle piston movement, fluid flows through small baseline orifices with minimal resistance. As piston velocity and pressure increase, the pressure flexes the first shim open, increasing flow area and allowing the piston to move with moderate resistance. At even higher velocities, additional shims flex progressively open, creating a smooth increase in damping force with velocity rather than an abrupt transition.

Modern high-performance shocks divide velocity-sensitive damping into distinct ranges: low-speed damping (LSC/LSR) controls body motions occurring at 0-1.5 inches per second piston velocity, including weight transfer during braking/acceleration, body roll in corners, and dive/squat motions; high-speed damping (HSC/HSR) controls impacts occurring above 1.5 inches per second, including bumps, potholes, rippled pavement, and curb strikes.

The distinction between low-speed and high-speed damping is crucial for optimizing ride and handling. Firms low-speed damping reduces body roll and improves handling response but can make the ride feel overly stiff and harsh. Firm high-speed damping controls impacts and prevents bottoming but, if too stiff, transmits harshness to the vehicle body. The ideal shock balances these requirements, allowing soft ride quality with firm control—achievable because low-speed and high-speed events occur at different piston velocities.

Some premium and adjustable shocks feature separate circuits for low-speed and high-speed damping, with different valve systems handling each range. This allows independent tuning: you can increase low-speed damping for better handling without making high-speed damping harsher, or soften high-speed damping for comfort without sacrificing low-speed control. Professional race teams spend countless hours optimizing these settings for specific tracks and vehicle setups.

The automatic nature of velocity-sensitive damping explains why traditional hydraulic shocks remain competitive even against modern electronic adaptive systems. A well-designed passive shock automatically provides appropriate damping for most conditions without the complexity, weight, and cost of electronic controls. However, passive shocks cannot change their fundamental characteristics—a shock tuned for sporty handling will ride firm on smooth roads, while a comfort-tuned shock won’t control aggressive driving well. This limitation is what drives development of adaptive systems that can change damping characteristics on demand.

Heat Management: Maintaining Performance Under Load

Every time a shock absorber moves, hydraulic friction converts kinetic energy into thermal energy—heat that must dissipate or accumulate until the fluid overheats and performance degrades. Heat management separates premium shocks from budget units and explains why some designs excel under sustained hard use while others fade quickly. Understanding thermal dynamics helps you select appropriate shocks for your driving style and recognize when heat-related fade occurs.

During normal driving on smooth highways, shock temperatures typically stabilize at 150-200°F—warm but well within operational limits. The shock generates heat during every compression and rebound cycle, but at moderate rates that the shock body and surrounding air can dissipate effectively. Under these conditions, even budget shocks perform adequately because heat generation remains manageable.

Demanding conditions generate much more heat: descending a mountain grade with repeated braking cycles, towing a heavy trailer in mountainous terrain, aggressive cornering on twisty roads, off-road driving over rough terrain, and sustained high-speed driving on rough pavement. These scenarios can push shock temperatures above 400°F, approaching fluid thermal limits and testing heat dissipation capacity.

As shock temperature rises, hydraulic fluid viscosity decreases—the fluid becomes thinner and flows more easily through valves and orifices. This reduced viscosity means the shock provides less damping force for the same piston velocity, causing fade. In severe cases, fluid can approach its boiling point, causing vapor formation (cavitation) that completely eliminates damping. Overheated shocks feel soft and unresponsive, the vehicle bounces excessively, handling becomes unpredictable, and braking distances increase.

Shock design dramatically affects heat management capability. Mono-tube shocks dissipate heat more effectively than twin-tubes because the working cylinder forms the outer tube with maximum surface area exposed to cooling airflow. The larger fluid capacity in mono-tubes also provides greater thermal mass to absorb heat before temperature rises significantly. This superior heat management explains why performance vehicles and heavy-duty applications favor mono-tube designs despite their higher cost.

Premium shock absorbers incorporate additional heat management features: larger diameter bodies increase surface area and fluid capacity, external cooling fins on some performance models increase convection, remote reservoirs (connected by hoses) on extreme applications allow heat dissipation away from the suspension area, synthetic hydraulic fluids maintain viscosity better at high temperatures, and high-temperature seals resist degradation at 400°F+ operating temperatures.

The practical implication is matching shock design to your usage. If you frequently tow heavy loads, drive aggressively on mountain roads, or use your vehicle for off-road adventures, invest in shocks designed for heat management—typically mono-tube designs from quality manufacturers. For normal daily driving on good roads with occasional highway trips, standard twin-tube shocks provide adequate performance and cost savings. Recognize that asking budget shocks to handle demanding conditions leads to premature fade and failure.

Gas Charging Function: Maintaining Solid Hydraulics

Gas charging technology transformed shock absorber performance by solving the cavitation problem that plagued early hydraulic dampers. While we discussed cavitation prevention earlier, understanding exactly how gas charging maintains solid hydraulic operation throughout the stroke range reveals why this technology became standard on modern shocks and how pressure differences affect performance.

The gas charge—always nitrogen, never air—maintains constant pressure on the hydraulic fluid throughout all operating conditions. This elevated base pressure ensures fluid pressure never drops below the vapor pressure threshold where dissolved gases would form bubbles. Nitrogen’s chemical inertness prevents oxidation and degradation of hydraulic fluid, while its inability to dissolve in hydraulic fluid prevents pressure loss over time.

In twin-tube gas shocks, the reserve chamber contains fluid on one side of a separator (bladder or piston) and nitrogen gas on the other. The gas pressurizes the fluid to approximately 100-150 PSI. This pressure forces fluid through the base valve into the working chamber under positive pressure, preventing suction cavitation during rapid rebound strokes. The relatively modest pressure keeps ride quality comfortable while providing cavitation protection.

Mono-tube shocks use much higher gas pressure—typically 200-360 PSI—maintained by the floating piston that directly separates working fluid from the nitrogen charge. This higher pressure provides superior cavitation protection under extreme conditions and allows faster shock response since the system is pre-pressurized. The floating piston moves freely within the pressure tube, accommodating volume changes as the piston rod enters and exits while maintaining constant gas pressure.

The gas charge pressure significantly affects shock behavior beyond cavitation prevention. Higher pressure provides firmer ride quality because the shock must overcome gas pressure before compression begins, slightly increases vehicle ride height (typically 0.25-0.75 inches) from the pressure pushing against the piston, improves small-bump compliance because the pre-pressurized system responds instantly, reduces suction during rapid extension strokes, and maintains more consistent damping across the full stroke range.

Professional suspension tuners sometimes adjust gas pressure in adjustable shocks to fine-tune performance. Increasing pressure firms the ride and raises the vehicle slightly, benefits high-speed driving or heavy loads. Decreasing pressure softens ride quality, helps with comfort-oriented setups. However, pressure cannot drop below minimum thresholds (typically 100 PSI for twin-tubes, 200 PSI for mono-tubes) or cavitation protection is lost.

Gas charge pressure gradually decreases over time as nitrogen molecules slowly permeate through seals and rubber components. This is normal aging—quality shocks lose 10-20 PSI over 5-7 years of service. When pressure drops below effective thresholds, cavitation and fade occur more readily, and the shock requires replacement. This aging characteristic is one reason why shocks are time-limited components even if they don’t show visible damage or leaks.

The practical takeaway is understanding that gas-charged shocks provide measurably superior performance compared to non-gas designs, justifying their slightly higher cost for all but the most basic economy applications. The firmer initial feel compared to non-gas shocks represents improved performance rather than harshness. If you notice your gas shocks becoming softer over time—indicating gas pressure loss—replacement restores original performance even if the shocks aren’t leaking fluid.

Where Are Shock Absorbers Located?

Shock absorbers mount at each wheel (four total on most vehicles) in positions that allow them to control suspension movement while remaining accessible for inspection and replacement. Understanding shock location, how to identify them visually, and what’s required to access them helps you maintain these critical safety components and recognize when professional service is necessary.

Front shock absorbers on most modern vehicles integrate into MacPherson strut assemblies mounted between the lower control arm and the upper strut tower. The strut tower is visible under the hood as a dome-shaped protrusion where the top of the strut mounts to the chassis. Three or four bolts secure the upper strut mount to this tower, while two large bolts attach the strut to the steering knuckle at the bottom. This configuration places the shock/strut in the center of the wheel, perfectly positioned to control wheel movement.

Rear shock absorbers vary significantly by vehicle design. On passenger cars with independent rear suspension, shocks often mount similarly to front struts or mount separately between the lower suspension arms and chassis. On trucks and SUVs with solid rear axles, conventional shock absorbers mount between brackets on the axle housing and mounting points on the vehicle frame. These are typically easier to access than struts since they mount as standalone components without integrated springs or structural duties.

Looking through your vehicle’s wheel spokes, you can usually identify the shock absorber as a substantial cylindrical component, typically 2-4 inches in diameter and 12-24 inches long. On strut-equipped vehicles, you’ll see the large strut assembly with the coil spring wrapped around it. On vehicles with conventional shocks, you’ll see the cylindrical shock body with rubber mounting bushings at each end. The piston rod extends from one end (usually the top) and connects to the chassis, while the shock body connects to the suspension or axle.

Visual identification features help distinguish shocks from other components: rubber dust boot covering the piston rod where it enters the shock body, hydraulic brake line or flexible hose running nearby (don’t confuse with shock), possible brake wear sensor wire or ABS sensor on the same mounting area, and spring (coil spring on struts, separate springs on conventional shock setups). Quality shocks often display brand names and part numbers on the shock body, while budget shocks may have minimal marking.

The mounting hardware deserves attention during inspection. Upper mounts use rubber bushings to isolate road vibration—these bushings should show no cracking, tears, or excessive softening. Lower mounts typically use larger rubber bushings or metal sleeves with rubber isolators. On struts, the upper mount includes a bearing that allows steering rotation; this bearing can wear and cause knocking noises during steering. Corroded or seized mounting bolts from road salt exposure complicate replacement and sometimes require cutting.

Access Requirements for Inspection and Replacement

For basic visual inspection—checking for leaks, damage, and obvious wear—you need the vehicle safely raised and supported on jack stands with wheels removed. Never work under a vehicle supported only by a floor jack; jack stands are mandatory for safety. A good flashlight helps inspect shock bodies for fluid leaks and physical damage. This level of inspection is appropriate for DIY mechanics of all skill levels with proper equipment.

For conventional shock replacement (not struts), an intermediate DIY mechanic can typically complete the job with standard tools: socket set (metric for most imports, SAE for domestic), breaker bar for tight bolts, jack and jack stands rated for the vehicle weight, torque wrench for proper reinstallation, penetrating oil for corroded fasteners, and high-temperature brake grease for bushing lubrication. The procedure involves removing mounting bolts, sliding the shock out of position, installing the new shock, and torquing fasteners to specification.

Strut replacement requires substantially more expertise and specialized equipment. The coil spring remains under extreme compression even when the vehicle is raised and the suspension hangs free. Removing the strut with the compressed spring requires a hydraulic spring compressor—a specialized tool that safely compresses the spring, allowing upper strut mount removal, strut extraction, and reassembly with the new strut. Improper spring compression technique causes spring release with over 1,000 pounds of force, resulting in severe injuries including broken bones, lacerations, and fatalities. This is not a beginner DIY project.

Many professionals and advanced DIY mechanics now opt for complete strut assemblies (quick struts) that arrive pre-assembled with the new strut, spring, upper mount, and hardware. These assemblies cost $50-$150 more per strut than shock cartridge replacement but eliminate the dangerous spring compression procedure entirely, reducing installation time by 50-70 percent and ensuring all components are new. The safety and time advantages make complete assemblies the smart choice for most strut replacements.

After strut replacement, four-wheel alignment is mandatory. Removing and reinstalling struts alters suspension geometry, affecting camber and potentially other alignment angles. Driving on improper alignment accelerates tire wear and compromises handling. Budget $100-$200 for alignment when replacing struts. Conventional shock replacement on vehicles with separate springs typically doesn’t require alignment since suspension geometry remains unchanged.

Professional installation is strongly recommended for most shock/strut replacement jobs unless you have significant mechanical experience, proper equipment, and a safe workspace. The cost of professional installation—typically $100-$200 for conventional shocks, $200-$400 for struts—is justified by the safety risk reduction, proper torque specifications, correct handling of brake lines and ABS sensors, and included alignment service when needed. For safety-critical suspension work, paying professionals provides peace of mind and warranty protection.

Critical Safety Note: Shock absorber replacement, especially struts, involves compressed springs under extreme tension (1,000+ pounds of force). Improper spring compression during strut replacement can cause catastrophic spring release, resulting in severe injury or death. This is a job for professional technicians with proper spring compressor equipment and training. DIY shock replacement should only be attempted by experienced mechanics with appropriate safety equipment and knowledge of proper procedures.

Signs of Worn Shock Absorbers: When to Replace

Shock absorbers wear gradually over time, making it difficult to notice performance degradation until symptoms become severe. Recognizing the warning signs of worn shocks helps you replace them before safety and vehicle control are significantly compromised. Modern vehicles depend on properly functioning shocks for electronic safety systems to work effectively, making timely replacement more critical than ever.

Excessive Bouncing: The Classic Symptom

The most recognizable sign of worn shocks is excessive bouncing after hitting a bump or when driving over undulating road surfaces. When your shocks are functioning properly, they should dampen spring oscillation within 1-2 bounce cycles. Worn shocks lose this damping ability, allowing the springs to bounce 3-5 times or more before settling. This creates a “floating” sensation on wavy roads and makes the vehicle feel unstable and disconnected from the pavement.

You can test shock condition with the simple bounce test: push down firmly on one corner of your vehicle (preferably over the wheel) and quickly release. A vehicle with good shocks will rise back to normal ride height and settle immediately, making perhaps one small rebound before stopping completely. If the corner bounces 2-3 times or more, the shock at that wheel has lost significant damping ability and requires replacement.

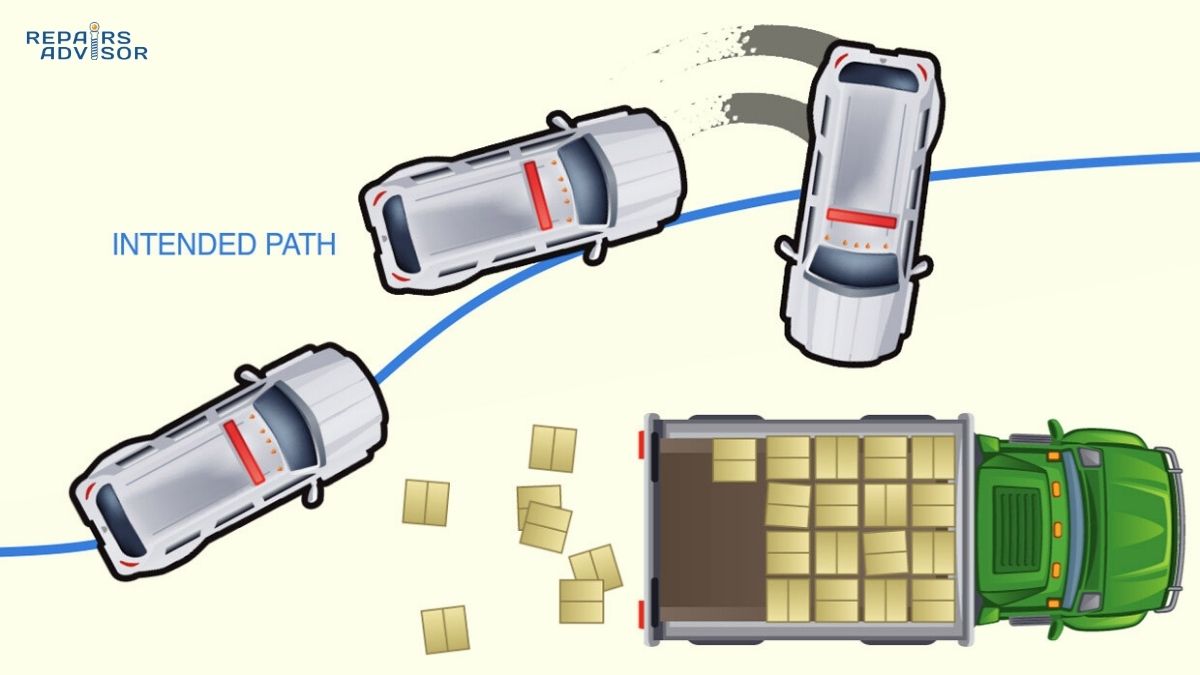

This excessive bouncing isn’t merely a comfort issue—it directly affects safety. When the suspension bounces, the tires intermittently lose firm contact with the road surface. During these moments of reduced contact pressure, steering response diminishes and braking effectiveness drops. If you need to make an emergency maneuver while the suspension is in a bounce cycle, vehicle response will be delayed and unpredictable. This is why worn shocks increase accident risk even though the failure mode doesn’t seem immediately dangerous.

The bouncing symptom often appears gradually. You might first notice excessive body motion on rough roads, then realize that highways with mild undulations cause noticeable bouncing, and eventually even smooth roads create a floating sensation because the shocks can’t control weight transfer during normal acceleration and braking. By the time bouncing is obvious, the shocks have lost 40-60% of their damping capacity and should be replaced immediately.

Nose Diving During Braking

When you apply the brakes, vehicle weight transfers forward—this is normal physics. Shock absorbers control how quickly and how much the front end dives during braking, maintaining proper suspension geometry and tire contact. Worn front shocks allow excessive nose dive where the front end dips dramatically toward the pavement while the rear rises up, creating an unstable braking platform.

This nose diving condition affects braking performance in multiple ways. The excessive weight transfer overloads the front tires while reducing rear tire contact, destabilizing the vehicle during hard braking. Front suspension compression changes wheel alignment angles, potentially reducing steering control during braking. The load on brake calipers and brake pads becomes uneven, with the front doing more work than intended. Most critically, braking distance increases—studies show worn shocks can increase stopping distance by 10-20%, which at 60 mph means an additional 15-30 feet before stopping.

The opposite condition—rear squat during acceleration—also indicates worn rear shocks. When accelerating, weight transfers rearward. Properly functioning rear shocks control this transfer, maintaining traction and stability. Worn rear shocks allow excessive squat where the rear suspension compresses dramatically while the front rises. This is particularly noticeable in trucks and SUVs when towing or hauling loads, where worn shocks allow dangerous suspension sagging and reduced steering control.

Modern vehicles with ABS systems and electronic stability control are especially compromised by worn shocks. These electronic systems depend on consistent tire contact and predictable suspension behavior to function correctly. When shocks allow excessive nose dive, the ABS system must work harder to prevent wheel lockup, and stability control may intervene unnecessarily or fail to intervene when needed because sensor inputs don’t match the control algorithms’ expectations.

If you notice that your vehicle “dives” when braking, requires longer stopping distances, or feels unstable during braking, have the shocks inspected immediately. This is a safety-critical symptom that directly affects your ability to stop in emergencies. Combined with other symptoms like bouncing or swaying, nose diving confirms that shock replacement should happen as soon as possible.

Body Roll and Sway in Turns

Properly functioning shock absorbers control body roll—the sideways tilting of the vehicle body during cornering—by managing weight transfer and suspension compression/extension rates. When shocks wear out, body roll increases dramatically, the vehicle feels unstable in turns, and excessive lean creates an unsafe sensation that reduces driver confidence and control.

During a turn, centrifugal force pushes the vehicle toward the outside of the curve. The suspension on the outside wheels compresses while the inside suspension extends. Shock absorbers should control these motions, allowing some roll for comfort while preventing excessive lean that compromises traction and stability. Worn shocks lose this control, allowing the vehicle to lean farther and take longer to settle into and out of corners.

The handling effects of worn shocks extend beyond just body roll. You may notice that steering response becomes slower—there’s a delay between turning the wheel and feeling the vehicle respond. The delay occurs because worn shocks allow suspension movement before tire grip increases, creating a disconnected feel. In emergency maneuvers like swerving to avoid an obstacle, this delayed response can mean the difference between successfully avoiding an accident and losing control.

Wind sensitivity is another indication of worn shocks affecting lateral stability. Strong crosswinds or passing large trucks should cause minor vehicle deflection that you easily correct with slight steering adjustments. With worn shocks, these wind gusts cause more dramatic vehicle movement requiring constant steering corrections. The vehicle may wander within its lane, requiring continuous small inputs to maintain course—a fatiguing and potentially dangerous condition on long highway drives.

Modern vehicles often include anti-roll bars (stabilizer bars) that mechanically resist body roll. However, these bars work in conjunction with shock absorbers—the bars reduce roll initiation, while shocks control the rate of roll and stabilize the vehicle during and after the turn. Worn shocks negate much of the anti-roll bar’s benefit because they can’t control the suspension movement the bar is trying to resist.

If your vehicle feels unstable in corners, requires constant steering corrections, or exhibits excessive body roll, worn shocks are likely contributing to the problem. While suspension geometry issues, worn bushings, or ball joints can also cause handling problems, shocks are often the culprit when body roll and sway are the primary symptoms. Professional inspection can determine if shocks or other suspension components need replacement.

Uneven Tire Wear: The Expensive Consequence

Shock absorbers maintain consistent tire contact with the road surface, ensuring even pressure distribution across the tire tread. When shocks wear out, they allow the tire to bounce or skip across the road surface, creating uneven contact pressure that accelerates tire wear in distinctive patterns. Recognizing these wear patterns helps identify shock problems before other symptoms become obvious.

The most characteristic tire wear pattern from worn shocks is cupping (also called scalloping)—a wavy, up-and-down wear pattern around the tire circumference. Run your hand around the tire tread in both directions; with cupping, the tread feels noticeably higher and lower as you move around the tire. This pattern develops because the bouncing tire makes uneven contact, wearing faster in areas of higher contact pressure. Cupping typically appears on both front or both rear tires, indicating worn shocks at that axle.

Other uneven wear patterns can also indicate shock problems. Flat spots or excessive center wear may result from the tire skipping and bouncing rather than rolling smoothly. One-sided wear (inner or outer edge) might suggest alignment problems exacerbated by shock wear—worn shocks allow suspension geometry to change during operation, creating inconsistent camber angles that accelerate edge wear. While alignment should always be checked when tire wear appears uneven, replacing worn shocks is often necessary to prevent the problem from recurring.

The financial impact of worn shocks on tire life is substantial. Quality tires costing $150-$300 each should last 50,000-70,000 miles with normal wear. Worn shocks can cut this lifespan in half, meaning a $600-$1,200 tire set might need replacement at 25,000-35,000 miles instead. The cost of new shocks ($400-$800 for four) is easily justified by extending tire life, not to mention the safety improvements from restoring proper damping.

When you notice uneven tire wear, have both tire alignment and shock absorbers inspected. Even if alignment is correct, installing new tires on worn shocks just accelerates wear on the new tires. Smart economics dictate replacing shocks before or at the same time as tires when wear patterns indicate shock problems. The combination of new tires and new shocks restores optimal performance and maximizes tire longevity.

Monitoring tire wear provides early warning of shock problems before other symptoms appear. During tire rotations (recommended every 5,000-7,000 miles), have the technician specifically check for cupping and unusual wear patterns. Catching shock wear early through tire inspection prevents the more dangerous symptoms like excessive bouncing and brake dive from developing to severe levels.

Visible Fluid Leaks: The Obvious Failure

Shock absorbers are sealed hydraulic devices—any visible fluid leakage indicates seal failure and requires immediate shock replacement. Unlike some automotive components where small leaks can be monitored, shock absorber leaks are progressive failures that rapidly worsen and eliminate damping capability. Learning to recognize shock leaks during visual inspection catches failures before complete damping loss occurs.

Check for leaks by inspecting the shock body, particularly around the piston rod seal at the top of the shock. Oil streaks running down from the seal area indicate fluid escaping past the seal. Fresh leaks appear wet and oily, while old leaks may look like dark, dirty streaks on the shock body. Even minor seepage—a slight dampness around the seal area—indicates seal degradation that will worsen rapidly. The piston rod surface below the seal may appear oily or have a thin film of fluid.

On strut-type shocks, the leak appears on the strut body below the upper mount. Fluid may accumulate on the strut and drip onto other components, creating an oily mess on the steering knuckle, brake caliper, and wheel. This leaking fluid is hydraulic oil, not brake fluid (which would indicate a brake hydraulic leak). Shock fluid typically appears clear to light amber in color, though aged fluid may darken.

The progression of seal failure follows a predictable pattern. Initial seal degradation causes minor seepage that appears as slight wetness around the seal. As the seal continues deteriorating, fluid weeps slowly, creating visible streaks on the shock body. Eventually, the seal fails more completely, allowing fluid to leak freely—you might see fluid dripping from the shock or pooled on the ground under the vehicle. At this point, the shock has lost most or all of its hydraulic fluid and provides minimal damping.

Once a shock starts leaking, rapid replacement is mandatory for several reasons. The leak is progressive—it will not stop or improve and will only worsen. Fluid loss directly eliminates damping capability—a shock with 50% fluid loss provides perhaps 20-30% of its designed damping force. The exposed piston rod surface becomes contaminated with dirt and debris, further damaging the seal. Complete seal failure can occur suddenly, immediately eliminating all damping at that wheel. Driving with leaking shocks is dangerous and can damage other suspension components due to excessive, uncontrolled movement.

While small amounts of dampness might appear on very old shocks without significant performance loss, any streak or visible fluid means the shock is actively leaking and needs replacement. Don’t try to monitor a leak—replace the shock as soon as the leak is discovered. Most shock manufacturers void warranties if you continue operating a leaking shock because the resulting damage (piston rod scoring, internal contamination) is preventable with timely replacement.

Physical Damage: Impact and Corrosion

Physical damage to shock absorbers from impacts, accidents, or corrosion requires immediate attention and typically means complete replacement. Unlike some wear symptoms that develop gradually, impact damage occurs suddenly and may not be immediately obvious unless you inspect the shocks after significant undercarriage impact or collision.

Bent piston rods are particularly serious. The piston rod must slide perfectly straight through the seal and guide. Any bend, even minor, causes the rod to bind during operation, accelerates seal wear, and creates uneven damping forces. Bending typically occurs from side impacts—hitting a curb while turning, running over road debris that strikes the shock, or collision damage that impacts suspension components. If you hit something hard enough to feel a severe jolt through the suspension, inspect all four shocks for piston rod damage.

Dented or damaged shock bodies compromise structural integrity and may affect internal components. A dent on a twin-tube shock outer body may not be critical if the inner pressure tube remains intact, but a dent on a mono-tube shock directly affects the working cylinder and can cause the piston to bind or seal damage. After any significant undercarriage impact—hitting a large rock, bottoming out severely, or collision damage—have shocks inspected by a professional.

Corrosion damage from road salt exposure is common in cold climates where salt is used for ice control. Surface corrosion on the shock body may only affect appearance, but corrosion near the piston rod seal accelerates seal failure. Rust pitting on the piston rod surface itself is critical—the rough surface damages seals, causing rapid fluid leakage. Corrosion on mounting hardware (bolts and brackets) can make replacement difficult or impossible without cutting corroded parts.

Mounting bushing damage is another form of physical failure. The rubber bushings that connect the shock to the chassis and suspension serve dual purposes: allowing necessary movement and isolating vibration. Torn, cracked, or severely deteriorated bushings allow excessive shock movement, create clunking or knocking noises, and reduce damping effectiveness even if the shock itself remains functional. Inspect bushings carefully during shock inspection—they’re inexpensive to replace but often overlooked.

The dust boot covering the piston rod and seal area isn’t just cosmetic—it protects the piston rod from road debris, dirt, and moisture that would damage the seal and rod surface. A torn or missing dust boot allows contamination entry, accelerating seal wear and causing premature leakage. If you notice dust boot damage during inspection, replacing it (if possible) or monitoring the shock more frequently helps prevent premature failure.

After any accident involving suspension damage, have all four shocks professionally inspected even if damage appears limited to one corner. The forces involved in a collision often affect components throughout the vehicle, and hidden damage may not be immediately apparent. The relatively low cost of shock inspection is worthwhile insurance against driving with compromised suspension that could fail unexpectedly or cause handling problems.

Increased Stopping Distance: The Safety-Critical Symptom

One of the most dangerous effects of worn shock absorbers is increased braking distance—the additional distance required to bring your vehicle to a complete stop. This symptom often goes unnoticed because the increase occurs gradually and because drivers adapt unconsciously to reduced braking performance. However, research definitively shows that worn shocks significantly impair braking effectiveness, creating substantial accident risk.

Multiple studies have quantified the braking distance penalty from worn shocks. The Monroe Institute of Technology found that vehicles with worn shocks require 20% greater stopping distance compared to the same vehicles with new shocks. At 55 mph, this means an additional 15-20 feet before stopping—potentially the difference between avoiding an accident and a collision. At highway speeds of 70 mph, the penalty increases to 25-35 feet. These aren’t trivial distances—they represent several car lengths at speeds where every foot matters.

The mechanism behind increased stopping distance involves multiple factors. Worn shocks allow excessive weight transfer during braking, overloading front tires while reducing rear tire contact. This weight distribution reduces overall braking efficiency because the rear brakes can’t contribute their designed force. Shock wear allows the wheels to bounce during braking on rough pavement, temporarily reducing tire contact and brake effectiveness. Worn shocks permit greater suspension travel during brake application, increasing the distance traveled before maximum brake force develops.

Modern vehicles with ABS complicate matters further. ABS systems depend on consistent wheel speed sensor signals and predictable tire behavior to modulate brake pressure correctly. Worn shocks allowing wheel bounce create erratic wheel speed signals that can cause the ABS to cycle unnecessarily or fail to cycle when needed, reducing braking effectiveness. In emergency stops on rough pavement—exactly when you need maximum braking—worn shocks can cause the ABS to malfunction.

Testing your own braking performance requires extreme caution and should only be done in safe conditions with no other traffic. In a large, empty parking lot, accelerate to 30 mph and brake hard (but not emergency hard initially). The vehicle should stop smoothly with progressive deceleration and no excessive nose dive. Try again from 40 mph if space permits. If you feel delayed brake engagement, excessive front-end dive, or a “soft” pedal feel despite proper brake maintenance, worn shocks may be compromising braking performance.

Professional brake testing can measure stopping distances accurately and compare results against manufacturer specifications. Many brake shops have dynamometers or testing equipment that identifies excessive stopping distances. When combined with visual shock inspection showing fluid leaks, damage, or worn mounting bushings, extended stopping distance provides strong evidence for immediate shock replacement.

If you notice that your vehicle takes longer to stop than expected, requires more brake pedal pressure, or feels unstable during hard braking, have both brakes and shocks inspected immediately. While brake system problems (worn pads, contaminated fluid, seized calipers) are more common causes of braking issues, worn shocks contribute significantly once other brake components are functioning properly. The safety implications demand urgent attention—don’t delay inspection and replacement when braking performance degrades.

Shock Absorber Replacement Cost and Considerations

Understanding shock absorber replacement costs helps you budget for this essential maintenance and make informed decisions about parts quality versus price. Shock replacement costs vary widely based on vehicle type, shock design (conventional versus struts), and parts quality. Smart shoppers balance cost against safety and longevity considerations.

Parts Cost: Economy to Premium Options

Economy and Standard Shocks ($50-$150 per shock) represent the budget tier suitable for basic transportation needs where performance isn’t critical and the vehicle has high mileage or limited remaining service life. Brands like Monroe OESpectrum, Gabriel, and entry-level KYB GR-2 populate this category. These shocks use simpler valve designs, fewer heat-management features, and may have shorter warranties (1-3 years). Expect these shocks to last 30,000-50,000 miles depending on driving conditions—adequate for vehicles near the end of their useful life but false economy for well-maintained vehicles you plan to keep long-term.

Premium Shocks ($150-$300 per shock) offer the best value for most drivers keeping their vehicles long-term. Bilstein, KYB Excel-G, Monroe OESpectrum Premium, and other quality brands deliver superior materials, better valve tuning, enhanced heat dissipation, and longer warranties (5-7 years or 50,000+ miles). The incremental cost over budget shocks—typically $400-$600 more for a complete set of four—easily justifies itself through extended service life, better performance, and reduced likelihood of premature failure. For most vehicles, premium shocks represent smart money management.

Performance Shocks ($200-$500+ per shock) target enthusiast drivers, heavy-duty applications, and vehicles requiring adjustable damping. Bilstein B6 and B8, KYB AGX, Koni, and race-oriented brands offer adjustable damping, superior heat management, exotic materials, and features like external reservoirs. These shocks handle track days, aggressive mountain driving, heavy towing, and extreme off-road use that would overwhelm standard shocks. Unless your driving demands these capabilities, premium non-adjustable shocks provide better value for street use.

Complete Strut Assemblies ($150-$400 per strut) include the shock cartridge, coil spring, upper mount, and hardware in a pre-assembled package. While more expensive than shock cartridge replacement alone, complete assemblies eliminate the dangerous spring compression procedure, reduce installation time by 50-70%, ensure all components are new rather than reusing potentially worn parts, and come with comprehensive warranties covering the entire assembly. For strut-equipped vehicles, complete assemblies offer the best combination of safety, reliability, and value despite higher parts cost.

Labor Costs and Installation Time

Labor costs vary significantly by shock type, vehicle accessibility, and regional labor rates. Conventional shock replacement typically costs $100-$200 in labor for both front or both rear shocks (pairs). Installation time ranges from 1-2 hours for accessible designs on mainstream vehicles to 3-4 hours for difficult installations on trucks or specialty vehicles. Many shops charge a fixed price per axle rather than hourly rates for this common service.

Strut replacement labor costs $200-$400 for both front or both rear struts, with installation taking 2-4 hours depending on vehicle design. The higher labor cost reflects the additional complexity of removing struts from steering knuckles, disconnecting brake lines and ABS sensors, removing upper strut mount hardware from the strut tower, and potentially using spring compressors (though complete assemblies eliminate this step). Some vehicles require removing other components (bumper covers, fender liners) to access struts, increasing labor time and cost.

Additional costs often apply to strut replacement. Wheel alignment is mandatory after strut replacement since removing and reinstalling struts alters suspension geometry—budget $100-$200 for a four-wheel alignment. Some vehicles require specialized tools or procedures that increase labor costs: pressed-in ball joints that must be removed to access struts, seized or corroded hardware requiring cutting and replacement, or electronic adaptive suspension systems requiring reprogramming. Discuss these potential additional costs upfront to avoid surprises.

Regional labor rates significantly affect total cost. Metropolitan areas with high costs of living charge $120-$180 per hour for automotive service, while rural areas may charge $80-$120 per hour. Dealerships typically charge 20-40% more than independent shops for the same work, though dealership service may include additional quality checks and warranty advantages. Get quotes from multiple shops to understand typical pricing in your area.

Total Cost Estimates by Vehicle Type

Economy Car (conventional shocks): Typical total cost ranges from $400-$700 for all four shocks including parts and labor. This assumes standard twin-tube gas shocks in the premium quality range with straightforward installation. Budget 2-3 hours shop time, no alignment required (shocks only, not struts).

Mid-Size Sedan (front struts): Total cost for front strut replacement runs $800-$1,200 including complete strut assemblies, installation, and wheel alignment. This represents the most common shock replacement scenario for modern passenger cars. Rear shocks (if conventional rather than strut-type) add $300-$500 if needed simultaneously.

SUV/Truck (heavy-duty conventional): Shock replacement for trucks and SUVs costs $800-$1,500 depending on shock size and quality. Heavy-duty shocks cost more, and larger vehicles require more labor time for access. Trucks used for towing benefit from premium mono-tube shocks despite higher initial cost. Consider vehicles like Ford, Toyota, and Honda trucks that may have specific shock requirements.

Performance Vehicle (sport shocks/coilovers): Total costs range from $1,200-$2,500+ for performance-oriented suspension upgrades. This category includes adjustable shocks, coilover conversions, and race-spec components. Labor costs increase for installation complexity and corner-balancing/tuning services. Ensure any performance modifications maintain appropriate safety margins for street use.

These estimates represent typical costs for quality work using appropriate parts. Always replace shocks in pairs (both front or both rear) rather than individually to maintain balanced handling. Replacing all four shocks simultaneously offers better vehicle performance and often includes labor discounts versus replacing front and rear separately.

OEM versus Aftermarket: Quality and Value Considerations

OEM (Original Equipment Manufacturer) shocks come from the same suppliers that provided shocks for your vehicle when new—brands like Bilstein, KYB, Sachs, or Monroe supply OEM parts to vehicle manufacturers. These shocks match original specifications exactly and typically represent premium quality. The OEM label commands a price premium of 25-50% over aftermarket equivalents, costing $200-$400 per shock through dealers. For maintained vehicles where long-term reliability matters, OEM shocks provide peace of mind and are especially appropriate for newer vehicles still under powertrain warranty.

Quality aftermarket shocks from recognized brands (Bilstein, KYB, Monroe, Koni) often exceed OEM specifications while costing less than dealer OEM prices. These manufacturers invest heavily in engineering and testing, produce shocks for multiple vehicle applications from the same production lines, and compete on performance and value rather than just price. Quality aftermarket shocks represent the sweet spot for most replacement scenarios—better performance than economy options, lower cost than OEM, and proven reliability with strong warranties.

Budget aftermarket shocks appeal on price alone but often prove false economy. No-name imports selling for $30-$50 per shock use inferior materials, simpler valve designs, lower-quality seals, and minimal heat management. These shocks may provide acceptable performance for 20,000-30,000 miles but degrade quickly and offer no warranty protection worth pursuing. The $200-$300 saved on a complete set evaporates when premature replacement becomes necessary, not counting the safety compromises during the shortened service life.

The recommendation for most vehicle owners is quality aftermarket shocks from established brands or OEM parts for newer/higher-value vehicles. The incremental cost difference between budget and quality shocks—$400-$600 for a complete set—is easily justified by doubled service life, superior performance, and reduced failure risk. For older vehicles near end of service life, budget shocks may suffice, but never compromise on safety by continuing to drive with failed shocks rather than replacing them with affordable options.

Professional Installation: Why It’s Worth the Cost

While shock replacement might seem straightforward—remove two bolts, install new shock, tighten bolts—numerous complications justify professional installation for most vehicle owners. Proper vehicle support is critical for safety; the vehicle must be raised high enough to access shocks while supported on jack stands (never just a floor jack) with wheels removed. Professional shops use hydraulic lifts that provide safe access and proper support, eliminating the risk of vehicle collapse that claims lives in home garages every year.

Torque specifications matter more than many realize. Shock mounting bolts require specific torque values—typically 60-120 ft-lbs depending on vehicle and location. Under-torquing allows mounting hardware to loosen, creating dangerous handling issues. Over-torquing can strip threads, crack mounts, or crush rubber bushings, causing premature failure. Professional technicians use calibrated torque wrenches and follow manufacturer specifications, ensuring proper installation.

Component interaction and routing requires expertise. Brake lines and ABS sensors often route near or attach to shocks and struts. Disconnecting these components without damage, routing them properly during reinstallation, and ensuring no interference with shock travel requires mechanical knowledge. Incorrect routing can cause brake line chafing and failure or ABS sensor damage, creating serious safety issues.