Modern vehicles can weigh well over 3,000 pounds, with a significant portion of that mass resting on the front wheels. Try steering a car without power assistance in a parking lot, and you’ll quickly appreciate why hydraulic power steering revolutionized driving when it became mainstream in the 1950s. This ingenious system uses pressurized hydraulic fluid to multiply your steering input force by 4 to 6 times, transforming the physically demanding task of turning heavy front wheels into the effortless experience we take for granted today.

Understanding how hydraulic power steering works helps you diagnose common issues like whining noises and hard steering, make informed maintenance decisions about fluid changes and system service, and appreciate why the automotive industry is transitioning to electronic power steering in modern vehicles. This article explains the core components, operating principles, and maintenance requirements of hydraulic power steering systems—knowledge that remains valuable for millions of vehicles still using this proven technology.

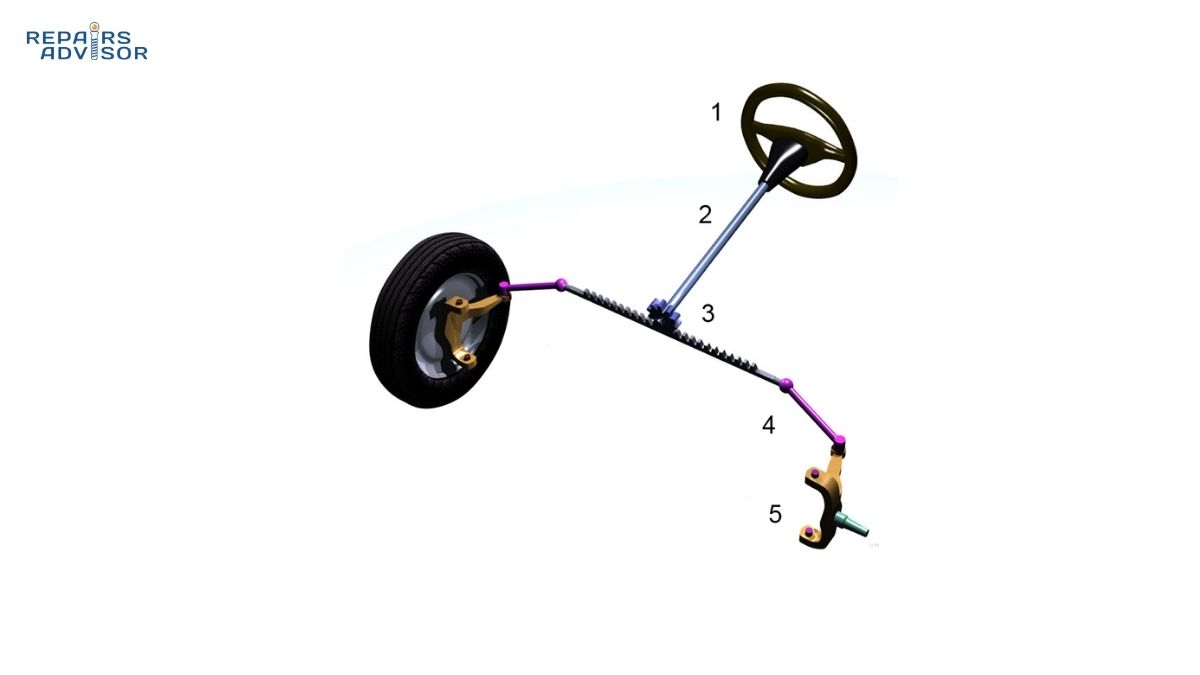

At its heart, a hydraulic power steering system consists of five main components working together in a closed loop: an engine-driven pump generating hydraulic pressure, a fluid reservoir storing the working fluid, a rotary valve sensing driver steering effort, a steering rack converting hydraulic pressure to mechanical force, and pressure hoses connecting everything together. Let’s explore how these components work individually and as an integrated system.

Core Components and System Architecture

The Power Steering Pump: Converting Mechanical Power to Hydraulic Pressure

The power steering pump serves as the hydraulic heart of the system, converting mechanical energy from the engine into hydraulic pressure. Most vehicles use a rotary-vane pump design driven by a serpentine belt connected to the engine crankshaft. Inside this pump, a series of retractable vanes spin within an oval-shaped chamber, creating expanding and contracting volumes as they rotate. This action pulls hydraulic fluid from the reservoir at low pressure on one side while simultaneously forcing it out at high pressure—typically 1,000 to 1,500 PSI—on the other side.

The pump’s output flow is directly tied to engine RPM, which presents an engineering challenge. The system must provide adequate flow when the engine idles at 600-800 RPM during parking maneuvers, but at highway speeds of 2,000+ RPM, the pump moves far more fluid than necessary. To prevent excessive pressure buildup at high engine speeds, power steering pumps incorporate a pressure-relief valve that opens when system pressure exceeds design limits, diverting excess flow back to the reservoir.

This “always on” characteristic means the pump runs continuously whenever the engine operates, even when you’re driving straight and need no steering assistance. This parasitic load consumes 2 to 5 horsepower, contributing to reduced fuel efficiency—a key reason why automakers have been transitioning to electronic power steering systems that only consume power when actively assisting.

The Fluid Reservoir: Storage and Filtration

The power steering fluid reservoir serves multiple functions beyond simple fluid storage. This component, typically mounted in the engine bay for easy access, holds between 0.5 and 1.0 liters of specialized hydraulic fluid depending on vehicle size. The reservoir features a sight glass or dipstick allowing quick visual inspection of fluid level and condition, plus an integrated filter screen that catches debris before it can enter the pump and damage precision-machined internal components.

The type of power steering fluid is critical and varies by manufacturer. Some systems use automatic transmission fluid (ATF), while others require synthetic or mineral-based hydraulic fluids with specific additives to protect seals and prevent foaming. Using the wrong fluid type can cause seal deterioration and system failure, making it essential to follow the manufacturer’s specifications found in your owner’s manual or stamped on the reservoir cap.

The Rotary Valve: Sensing Driver Effort and Directing Fluid Flow

The rotary valve represents the “intelligence” of the hydraulic power steering system. Located inside the steering rack or gearbox where it connects to the steering column, this sophisticated component senses how much effort you’re applying to the steering wheel and proportionally directs hydraulic assistance. At its core is a torsion bar—a thin metal rod designed to twist precisely under torque. The amount of twist directly correlates to your steering effort.

The torsion bar connects the steering wheel input on one end to the pinion gear or worm gear that turns the wheels on the other end. When you turn the steering wheel, the torsion bar twists before the wheels begin to turn. This deflection creates a slight angular difference between the input shaft (from your steering wheel) and the output shaft (to the wheels). A spool valve assembly surrounding the torsion bar responds to this angular difference by opening and closing hydraulic ports.

When driving straight, the spool valve remains centered and hydraulic pressure equalizes on both sides of the steering rack piston—no assist is provided. The moment you begin turning, the torsion bar twists, the spool valve shifts position, and high-pressure ports open to direct fluid to the appropriate side of the rack piston. Greater steering effort causes more torsion bar twist, more valve opening, and proportionally more hydraulic assistance. This elegant mechanical feedback system ensures the assistance always matches your input force.

The Hydraulic Steering Rack: Converting Pressure to Linear Force

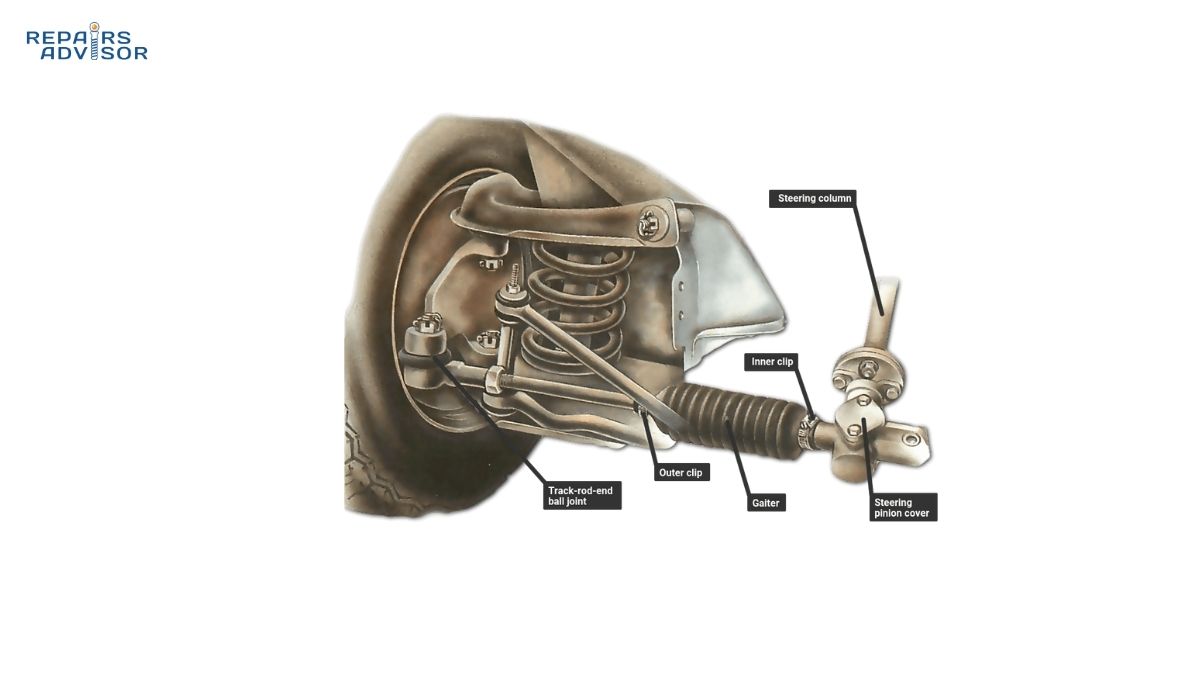

In most modern vehicles with hydraulic power steering, the steering rack incorporates a hydraulic cylinder and piston assembly. The rack itself is a toothed bar that moves left and right within a housing, with a pinion gear at one end meshing with the rack teeth to convert steering wheel rotation into linear rack motion. The hydraulic assist comes from a piston attached to the rack, sliding inside a sealed cylinder that’s integrated into the rack assembly.

When the rotary valve directs high-pressure fluid to one side of this piston, the hydraulic pressure (up to 1,500 PSI) multiplied by the piston’s surface area generates substantial force—often hundreds of pounds—that assists in moving the rack. The beauty of this design is that it maintains a direct mechanical connection between the steering wheel and wheels. If the hydraulic system fails completely, you can still steer the vehicle manually; it just requires significantly more effort, similar to cars built before power steering became standard.

The rack’s linear motion is transmitted through tie rods to the steering knuckles at each front wheel, converting the rack’s side-to-side movement into wheel pivoting around their steering axes. This mechanical linkage ensures that steering response is immediate and predictable.

Pressure Hoses and Hydraulic Lines

The final major components are the hydraulic hoses connecting the pump, valve, rack, and reservoir. The high-pressure supply hose from the pump to the steering rack must withstand operating pressures exceeding 1,000 PSI, requiring reinforced rubber construction or braided steel sheathing. The low-pressure return hose from the rack back to the reservoir operates at much lower pressure and can use simpler construction.

These hoses are common failure points in aging hydraulic power steering systems. The rubber deteriorates over time due to heat exposure, flexing, and chemical degradation from the hydraulic fluid itself. Small seepage leaks can progress to complete hose rupture, causing sudden loss of power assistance and creating a potential safety hazard. Proper hose routing during installation—away from hot exhaust components and sharp edges—extends service life significantly.

Operating Principles: From Driver Input to Steering Assist

Understanding how these components work together reveals the elegant simplicity of hydraulic power steering. The process flows through five distinct steps each time you turn the steering wheel.

Step 1: Continuous Hydraulic Circulation

From the moment you start your engine, the belt-driven power steering pump begins creating a continuous flow of pressurized hydraulic fluid. The fluid follows a closed-loop path: from the reservoir, through the pump where it’s pressurized, to the rotary valve in the steering rack, and back to the reservoir through the low-pressure return line. This constant circulation happens regardless of whether you’re actually turning the steering wheel, which is why the system consumes 2 to 5 horsepower continuously—a parasitic load that impacts fuel economy.

Step 2: Sensing Driver Steering Effort

When you begin turning the steering wheel, that rotational force travels down the steering column to the rotary valve’s torsion bar. The torsion bar is specifically calibrated to twist in proportion to the torque you apply. A light steering input during a gentle lane change causes minimal torsion bar deflection, while a heavy steering input during a parking maneuver twists the bar significantly. This mechanical twist serves as the system’s primary sensor—no electronics required, just precise metallurgy and mechanical design.

Step 3: Directing Hydraulic Flow

The torsion bar’s deflection causes the spool valve assembly to rotate slightly relative to the valve body. This rotation opens hydraulic ports on one side while restricting flow on the other. For a left turn, the valve opens ports directing high-pressure fluid to the left side of the steering rack piston. For a right turn, it opens ports to the right side. The pressure differential between the assist and non-assist sides of the piston can reach 1,000 PSI or more. Meanwhile, fluid on the non-assist side drains freely back to the reservoir through the return line.

The more you twist the torsion bar (the harder you turn), the more the valve ports open, allowing greater fluid flow to the assist side. This proportional response ensures the hydraulic assistance always matches your steering effort—light touch yields gentle assist, forceful turning yields maximum assist.

Step 4: Hydraulic Force Multiplication

Here’s where Pascal’s principle of hydraulics delivers its benefit. The high-pressure fluid acting on the rack piston’s surface area generates force according to the equation: Force = Pressure × Area. With pressures of 1,000+ PSI and a piston several square inches in area, the hydraulic system can easily generate 200 to 400 pounds of assistive force. This force acts in parallel with your mechanical steering input, effectively multiplying your effort by a factor of 4 to 6 times.

This force multiplication is what transforms steering a 3,500-pound vehicle with wide tires from an exhausting workout into an effortless task. The system provides just enough assistance to make steering comfortable while preserving enough feedback through the torsion bar that you maintain a feel for the road surface and tire traction.

Step 5: Rack Movement and Wheel Response

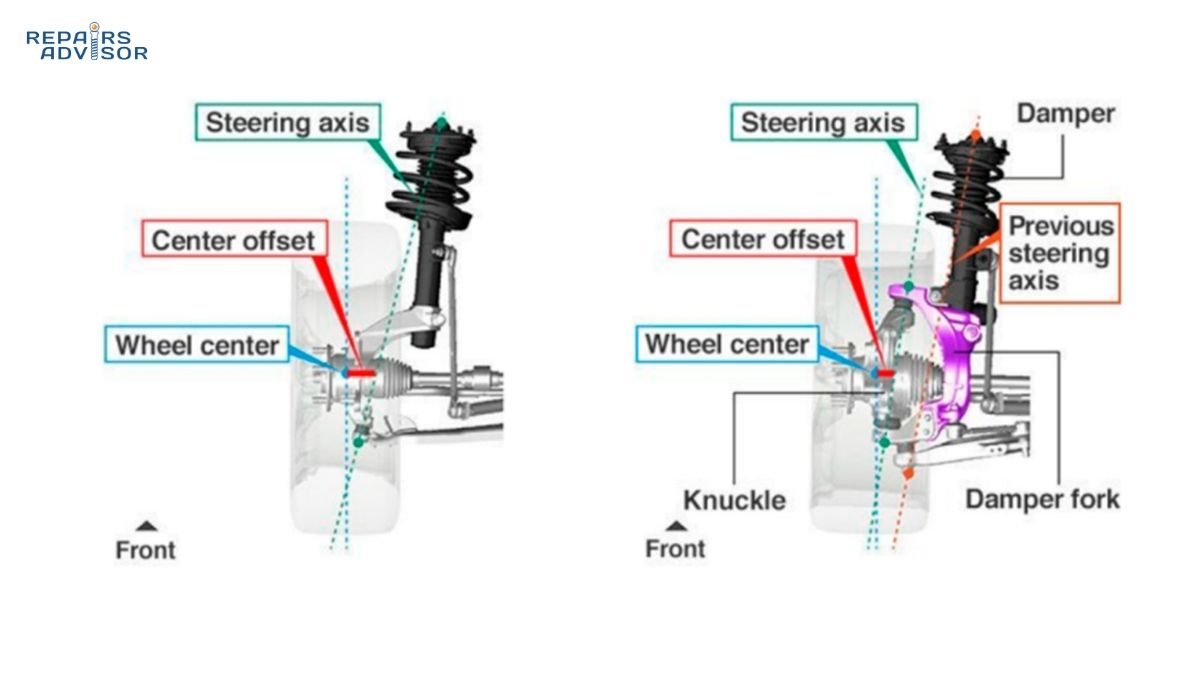

The combined force from your mechanical input plus the hydraulic assist pushes the steering rack in the intended direction. This linear rack movement is transmitted through the tie rods to each front wheel’s steering knuckle, causing the wheels to pivot. The geometry of this linkage system follows specific principles of steering geometry to ensure both front wheels turn at appropriate angles for smooth cornering without tire scrubbing.

As the rack moves, fluid on the non-assist side of the piston flows freely back to the reservoir through the return line, while the pump continues supplying fresh pressurized fluid to the assist side. When you complete the turn and center the steering wheel, the torsion bar unwinds, the spool valve returns to its neutral position, pressure equalizes on both sides of the piston, and the system stands ready for the next steering input.

Speed-Sensitive Steering Considerations

Traditional hydraulic power steering systems provide constant assistance regardless of vehicle speed, but this isn’t ideal. Maximum assist is beneficial during low-speed parking maneuvers but can make highway steering feel artificially light or “numb,” reducing driver feedback at speeds where you need precise control. Some advanced hydraulic systems address this with speed-sensitive variable assist.

These systems use an electronically controlled valve that modulates hydraulic pressure based on vehicle speed sensor input—similar technology to EPS control systems but applied to hydraulic circuits. At parking lot speeds, full pressure flows to the rack for maximum assist. As speed increases, the electronic valve progressively restricts flow or diverts some fluid back to the reservoir, reducing assistance and providing better road feel at highway speeds. This compromise delivers the best of both worlds but adds complexity and cost to the system.

Advantages, Disadvantages, and the Evolution to Electric

Hydraulic power steering dominated the automotive industry for over 50 years because it offered compelling advantages. However, the technology also carries inherent limitations that have driven the industry’s shift to electronic power steering in recent years.

The Case for Hydraulic Systems

Exceptional Road Feel: The direct hydraulic connection between steering wheel and road, mediated by a precision-calibrated torsion bar, provides steering feedback that many drivers—especially enthusiasts and professional drivers—consider superior to early electric systems. The torsion bar naturally communicates road surface texture, tire traction limits, and vehicle loading through subtle resistance changes. This tactile information helps drivers make better decisions about vehicle control, particularly during spirited driving or challenging conditions.

Proven Reliability and Simplicity: With more than half a century of development and refinement, hydraulic power steering systems are thoroughly understood by technicians worldwide. The mechanical-hydraulic design has few electronic components to fail, operates reliably across extreme temperature ranges from Arctic cold to desert heat, and continues functioning even when contaminated fluid or worn components reduce efficiency. The robust nature of hydraulic systems makes them particularly suitable for heavy-duty applications like commercial trucks, off-road vehicles, and performance cars that subject steering components to sustained high loads.

Powerful Assist Capability: Hydraulic systems can generate substantial assist forces without the current-draw limitations that constrain electric motors. This advantage matters for heavy vehicles with large front tires, lifted trucks with increased scrub radius, or vehicles requiring aggressive steering efforts. The hydraulic pump can sustain maximum output continuously without overheating, whereas electric motors must manage thermal limits during extended operation.

Service and Repair Economics: Because hydraulic power steering is mature technology, replacement parts are widely available, repair procedures are well-documented, and most independent repair shops possess the tools and expertise needed for service. Component costs tend to be reasonable, and even DIYers with intermediate skills can tackle some maintenance tasks like fluid changes and leak detection. This serviceability advantage extends the useful life of vehicles equipped with hydraulic systems.

The Limitations Driving Change

Fuel Efficiency Penalty: The continuously operating pump consumes 2 to 5 horsepower whenever the engine runs, regardless of whether steering assistance is actually needed. During highway cruising when steering inputs are minimal, this parasitic load wastes fuel—estimates suggest a 0.2 to 0.3 MPG penalty on average. While seemingly small, this inefficiency contradicts modern mandates for reduced fuel consumption and CO2 emissions, making hydraulic systems increasingly difficult to justify from an environmental perspective.

Maintenance Requirements and Failure Modes: Hydraulic systems demand regular fluid service every 50,000 to 100,000 miles, and the multiple hoses, seals, and connections create numerous potential leak points. Fluid leaks are the most common hydraulic power steering problem, often appearing first as seepage around hose connections, pump shaft seals, or rack end seals. Over time, exposure to engine heat, ozone, and repeated flexing causes rubber hoses to deteriorate, crack, and eventually fail. These maintenance requirements and failure modes add ongoing service costs that electric systems largely eliminate.

Packaging Complexity: A complete hydraulic system requires substantial engine bay space for the pump, reservoir, hoses, and fluid cooler (on some high-performance or heavy-duty applications). Modern engines are already densely packed, and finding room for hydraulic components while maintaining adequate service access challenges engineers. The routing of high-pressure hoses from the engine-mounted pump to the chassis-mounted steering rack also complicates manufacturing and assembly.

Limited Tuning Flexibility: Traditional hydraulic systems provide fixed assist characteristics determined by pump displacement, pressure settings, and torsion bar stiffness—mechanical parameters difficult to adjust after manufacturing. While variable-assist systems can modulate pressure based on speed, they lack the sophisticated assist curves and integration with vehicle dynamics systems that electric power steering enables. Modern stability control, lane-keeping assist, and automated parking features all benefit from the millisecond-level control authority that electric steering provides.

The automotive industry’s transition to electric power steering accelerated in the 2000s as electric motor technology matured and fuel economy regulations tightened. Today, most new cars use electric assist, though hydraulic systems remain common in trucks, performance vehicles, and the massive installed base of existing vehicles. Understanding hydraulic principles remains valuable—these systems will be serviced and maintained for decades to come, and many of the fundamental concepts carry forward to electronic power steering and other vehicle control systems like car suspension.

Common Problems, Maintenance, and When to Seek Help

Hydraulic power steering systems generally provide reliable service for 100,000 miles or more when properly maintained, but certain failure modes and maintenance needs are worth understanding.

Recognizing Common Failure Modes

Fluid Leaks: The Most Frequent Problem

Pink or red puddles beneath your parked vehicle often indicate power steering fluid leaks. These typically start as small seepage around hose connections, pump shaft seals, or rack end seals, gradually worsening as rubber components age and deteriorate. Early-stage leaks may only cause fluid level drops over weeks, but advanced leaks can drain the reservoir in days or even hours. As fluid level falls, steering effort increases progressively—at first noticeable mainly during parking maneuvers, eventually making all steering difficult.

For beginners, checking fluid level weekly if you suspect leaks is straightforward: locate the reservoir (usually a translucent plastic tank in the engine bay), check the level against minimum/maximum marks, and top up with the manufacturer-specified fluid if low. However, addressing the actual leak source requires professional diagnosis and repair. Hose replacement, pump seal service, or rack seal repair all demand specialized knowledge, proper tools, and often wheel alignment afterward since disturbing steering linkage components affects steering geometry settings.

Pump Failure and Noise

A failing power steering pump announces itself through distinctive noises: whining that increases with engine RPM, groaning sounds especially prominent when steering at low speeds, or squealing from belt slippage under load. These sounds often worsen when the fluid is cold, sometimes quieting after the engine warms up as viscosity decreases. Complete pump failure results in total loss of power assist—the steering wheel suddenly requires much greater force to turn, creating a potential safety hazard if it occurs unexpectedly.

Pump problems stem from several causes: worn internal bearings create noise and reduce efficiency, damaged vanes prevent proper pressure generation, contaminated fluid accelerates wear, and belt slippage (from wear or improper tension) prevents the pump from spinning at design speed. Professional diagnosis identifies the root cause, but pump replacement is almost always the recommended repair rather than rebuilding, given the labor-intensive nature of pump service and the ready availability of remanufactured units.

Contaminated or Degraded Fluid

Fresh power steering fluid appears clear to amber in color, sometimes with a reddish tint. Fluid that has degraded through age, heat, or contamination turns dark brown to black and may develop a burnt odor. Foamy fluid containing air bubbles indicates either air intrusion through loose connections or fluid breakdown causing foaming. Any of these conditions reduces the fluid’s ability to transmit hydraulic pressure and lubricate moving parts effectively.

Checking fluid condition is straightforward—remove the reservoir cap and inspect the fluid’s color and consistency. Dark, dirty, or foamy fluid warrants changing. Intermediate DIYers can perform a partial fluid exchange using a turkey baster or fluid extractor to remove old fluid from the reservoir, then refilling with fresh fluid and repeating the process several times while turning the steering lock-to-lock to cycle fluid through the system. However, this method doesn’t replace all fluid since significant volume remains in the hoses and rack. Professional shops use pressure exchange equipment that achieves more complete fluid replacement.

Steering System Noise from Air Intrusion

Air trapped in the hydraulic circuit causes whining, groaning, or moaning sounds, often accompanied by inconsistent power assist—sometimes strong, sometimes weak. Air typically enters through loose connections, failed seals allowing suction at the pump inlet, or after service when the system wasn’t properly bled. Unlike air in brake systems, which is a major safety concern, air in power steering mainly affects performance and comfort rather than posing immediate danger.

Bleeding the system requires turning the steering wheel fully left and right numerous times with the engine running, allowing trapped air bubbles to work their way to the reservoir where they can escape. Advanced methods involve raising the front wheels off the ground so the steering turns freely without load, performing 20 or more lock-to-lock cycles, and watching for bubbles in the reservoir fluid. Complete bleeding sometimes requires professional vacuum equipment that extracts air from the highest points in the system.

Maintenance Best Practices for Longevity

Regular Fluid Service

Most manufacturers recommend power steering fluid inspection at every oil change and fluid replacement every 50,000 to 100,000 miles. This interval varies significantly—some manufacturers consider power steering fluid “lifetime” and specify no service interval, while others mandate changes every 30,000 miles for severe service conditions. Your owner’s manual provides the authoritative schedule for your specific vehicle.

Critical point: ALWAYS use the exact fluid type specified by the manufacturer. Power steering systems are designed around specific fluid formulations, and using the wrong type—even if it’s quality fluid—can damage seals, cause foaming, or lead to system failure. The correct fluid type is usually printed on the reservoir cap or listed in your owner’s manual. Common types include ATF Dexron III/VI, synthetic power steering fluid, or mineral-based formulations. These are not interchangeable.

System Inspection and Early Problem Detection

Regular visual inspection catches problems before they escalate. During routine oil changes or other underhood service, look for:

- Fluid residue or dampness around hose connections, pump body, and rack boots (early leak indicators)

- Hose condition—cracks, abrasions, swelling, or hardening indicating deterioration

- Belt condition—glazing, fraying, cracking, or improper tension

- Fluid level and color in the reservoir

Monitoring changes in steering feel provides early warning of developing problems. Increasing steering effort, new noises, vibrations through the steering wheel, or inconsistent assist all warrant prompt professional inspection. Catching issues early—when a hose shows dampness but hasn’t ruptured, or when pump noise just begins—often allows less expensive preventive repairs before catastrophic failure.

Understanding Your DIY Boundaries and When to Call Professionals

The safety-critical nature of steering systems makes it essential to recognize which tasks are appropriate for DIYers versus those requiring professional expertise. Modern vehicles integrate steering with multiple safety systems including ABS, stability control, and collision avoidance features that all share data from steering angle sensors. Improper repairs can compromise these critical safety systems.

Appropriate for Intermediate DIYers:

- Checking and topping up fluid level

- Visual inspection for leaks, worn hoses, and belt condition

- Checking belt tension and condition

- Partial fluid change using turkey baster or extractor method

Requires Professional Service:

- Any repairs involving pump, rack, or hose replacement

- Complete system fluid flush with pressure equipment

- Bleeding after significant repairs

- Diagnosing complex noises or steering problems

- Any work on steering linkage requiring wheel alignment afterward

Immediate Professional Consultation Critical:

- Complete loss of power assist while driving

- Sudden steering wheel kickback or binding

- Major fluid leak (puddles forming, not just dampness)

- Steering wheel turns but wheels don’t respond

- Any steering behavior that feels unsafe or unpredictable

Safety Disclaimer: Steering system failures can result in loss of vehicle control and serious accidents. If you experience sudden changes in steering performance, unusual noises, difficulty turning, or discover major fluid leaks, have the system professionally inspected immediately before driving further. While checking fluid levels is a straightforward maintenance task, repairs to pumps, steering racks, and hydraulic lines require proper tools, technical knowledge, and often wheel alignment service afterward to ensure safe operation. When in doubt, consult a qualified technician.

Conclusion: Understanding a Proven Technology in Transition

Hydraulic power steering stands as one of the automotive industry’s most successful technologies, transforming vehicle control for over six decades. The system’s elegance lies in its mechanical simplicity—an engine-driven pump creating hydraulic pressure, a torsion bar sensing driver effort, a rotary valve directing fluid flow proportionally, and a hydraulic piston multiplying steering force. This direct hydraulic-mechanical coupling provides the superior road feel that many driving enthusiasts still prefer, while proven reliability and robust assist capability continue to make hydraulic systems the choice for heavy-duty applications.

Yet the technology’s inherent limitations—continuous power consumption impacting fuel economy, maintenance requirements from numerous fluid connections, and packaging complexity in modern engine bays—have driven the industry’s shift to electronic power steering. The transition reflects changing priorities: fuel efficiency and emissions regulations, integration with advanced driver assistance systems, and manufacturing simplification now outweigh the road feel advantages that hydraulic systems traditionally offered.

For vehicle owners, understanding hydraulic power steering operation enables better maintenance decisions and early problem recognition. Regular fluid service, visual inspection for leaks and worn components, and attention to changes in steering feel prevent minor issues from escalating into expensive failures or safety hazards. Knowing when to handle simple tasks like fluid checking versus when to seek professional help for repairs maintains system safety and reliability.

Whether your vehicle uses hydraulic steering or you’re simply interested in automotive technology, recognizing how these systems work provides valuable context. The fundamental principles of hydraulic force multiplication, proportional control through mechanical feedback, and the engineering compromises between assistance and driver feel apply broadly across vehicle control systems. As vehicles continue evolving toward integrated dynamics control and eventually autonomous operation, the proven reliability of hydraulic power steering reminds us that sometimes the “old” technology represents decades of refinement addressing real-world needs.

Your Next Steps:

If you own a vehicle with hydraulic power steering, take a moment to check your power steering fluid level and condition. The reservoir is typically easily accessible in your engine bay—consult your owner’s manual if you’re unsure of its location. While you’re there, inspect the visible portions of hoses for cracks, dampness, or deterioration. If your vehicle has exceeded 100,000 miles or is more than 10 years old without recent power steering service, consider having a professional technician inspect the system and potentially service the fluid.

For those researching vehicles or planning future purchases, understanding the differences between hydraulic and electric power steering systems helps you make informed decisions. Many modern vehicles offer excellent electric steering that provides efficiency and advanced features, though some performance vehicles and trucks retain hydraulic systems for their proven capability and superior feedback. As with many automotive technologies, there’s no universally “best” choice—the ideal system depends on your specific needs, priorities, and intended vehicle use.