Every time you turn your ignition key or press the start button, a compact yet powerful electric motor springs into action, converting battery power into the mechanical force needed to crank your engine. This unsung hero—the starter motor—performs one of the most demanding jobs in your vehicle, drawing massive electrical current and generating tremendous torque to overcome engine compression and initiate the combustion cycle. Without a functioning starter motor, even a perfectly maintained engine remains silent, leaving you stranded until the problem is resolved.

Understanding how starter motors work transforms frustrating no-start situations from mysterious failures into diagnosable problems. The starting system integrates multiple components—battery, starter relay, solenoid, and the motor itself—each playing a critical role in the split-second sequence that brings your engine to life. This comprehensive guide explains the electromagnetic principles behind starter motor operation, details the internal components that make cranking possible, walks through the complete starting sequence step by step, and provides professional diagnostic procedures for identifying and resolving common starting problems.

Whether you’re a DIY enthusiast looking to diagnose a slow-cranking condition, a professional mechanic seeking deeper technical knowledge, or simply curious about how your vehicle’s starting system functions, this article delivers the authoritative information you need. We’ll explore why starter motors can draw 150-300 amps during cranking, how the solenoid performs two critical functions simultaneously, what those clicking or grinding noises actually mean, and when professional service is required versus when you can safely tackle the repair yourself.

Understanding the Starter Motor’s Role in Your Vehicle

Internal combustion engines operate as feedback systems—once running, each combustion cycle provides the energy needed to initiate the next cycle. The third stroke releases power from burning fuel, which drives the fourth exhaust stroke and also powers the first two strokes of the next cycle through rotational inertia stored in the flywheel. However, at zero RPM with the engine completely stopped, this feedback loop doesn’t exist. The engine cannot draw in an air-fuel mixture, compress it, or generate the spark needed for ignition without first being rotated by an external force. This is where the starter motor becomes essential.

Before electric starters became standard equipment in the 1920s, drivers had to hand-crank their engines—a physically demanding and sometimes dangerous task that required significant strength and proper timing. Modern starter motors eliminate this challenge by providing reliable, effortless starting at the touch of a button or turn of a key. The starting system comprises several interconnected components working in precise coordination: the car battery stores electrical energy, the ignition switch initiates the starting sequence, the starter relay amplifies the control signal, and the starter motor assembly converts electrical power into mechanical rotation.

The starter motor achieves its impressive cranking power through mechanical advantage. A typical starter motor features a small pinion gear with 8-12 teeth that engages with the engine’s flywheel ring gear containing 120-150 teeth. This creates a gear reduction ratio between 15:1 and 20:1, meaning the flywheel rotates much slower than the starter motor itself but with proportionally increased torque. This mechanical multiplication allows a relatively compact electric motor drawing 12 volts from the battery to generate enough force to rotate a multi-cylinder engine against compression resistance, friction, and inertia.

Modern permanent magnet starters represent a significant advancement over older field coil designs. Introduced widely in the 1990s, these compact motors use rare-earth permanent magnets instead of electromagnetic field coils, reducing weight by 30-40% while maintaining or improving cranking performance. Many contemporary starters also incorporate planetary gear reduction systems between the armature shaft and pinion gear, enabling even smaller motors to deliver the necessary torque. Despite their reduced size, these advanced starters can deliver 1.5-2.5 kilowatts of mechanical power during cranking—impressive output from a device weighing just 10-15 pounds.

The starting system integrates closely with other vehicle systems for proper operation and safety. Automatic transmission vehicles feature a neutral safety switch that prevents starter engagement unless the transmission is in Park or Neutral, eliminating the dangerous possibility of the vehicle lurching forward when starting. Manual transmission vehicles employ a clutch safety switch requiring the clutch pedal to be fully depressed before allowing starter operation. Modern vehicles with advanced security systems integrate immobilizer technology into the ignition system, electronically verifying the correct key before enabling the starting circuit. Additionally, the Engine Control Unit monitors cranking speed and adjusts fuel injection timing and duration to optimize cold-start performance under varying temperature conditions.

Safety Note: The starter motor draws extremely high current—typically 150-300 amperes—during operation, generating substantial heat in both the motor and electrical connections. Continuous cranking should never exceed 10-15 seconds, as prolonged operation can overheat the motor windings, damage the solenoid contacts, and severely drain the battery. If the engine fails to start, wait 30-60 seconds between cranking attempts to allow the electrical system and starter motor to cool. Repeated extended cranking without cooling intervals can cause permanent damage to the starter motor and may indicate an underlying engine problem requiring professional diagnosis.

Inside the Starter Motor: Component Breakdown

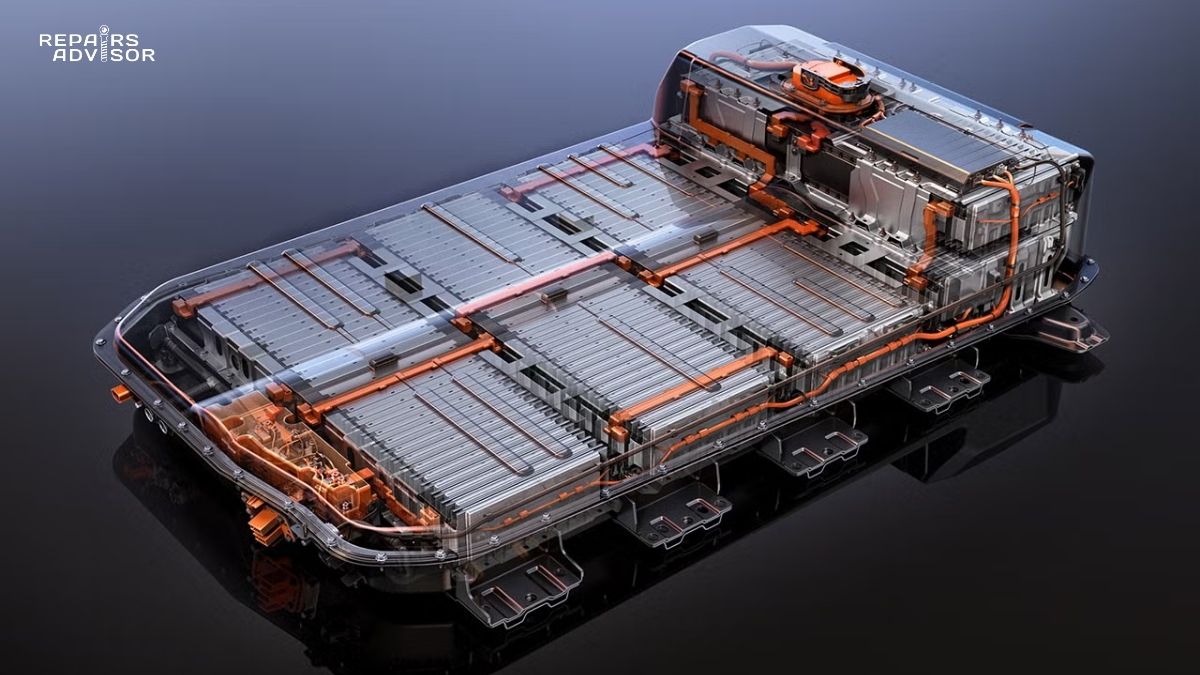

A starter motor assembly integrates a high-torque electric motor, electromagnetic solenoid, and mechanical drive system into a compact package weighing 15-25 pounds. Understanding the function of each internal component reveals how this device converts 12-volt DC electrical energy into the mechanical force needed to rotate your engine’s flywheel at 150-250 RPM. The sophistication of modern starter designs becomes apparent when examining the precision engineering required to reliably deliver this performance through hundreds of thousands of starting cycles.

Electric Motor Assembly

The heart of the starter is a series-wound DC motor optimized for high starting torque rather than continuous operation. At the center rotates the armature assembly, consisting of a laminated soft iron core with precisely wound copper conductors arranged in slots around its circumference. This armature core construction uses thin iron laminations stacked and bonded together rather than a solid iron cylinder, which significantly reduces energy-wasting eddy currents induced by the rapidly changing magnetic fields during operation. The armature rotates on hardened steel shaft bearings, with the shaft extending through both ends of the motor housing—one end connecting to the drive mechanism, the other to the commutator.

The commutator serves as a mechanical switching mechanism, automatically reversing current direction through the armature windings as the shaft rotates. This cylindrical component consists of copper segments insulated from each other by mica separators, with each segment connecting to specific armature coil ends. As the commutator rotates, spring-loaded carbon brushes maintain sliding electrical contact with the segments, feeding current into the armature windings. The brushes are precisely positioned so that current reversal occurs at the optimal point in the rotation cycle, maintaining continuous torque production in one direction. Brush wear represents the most common long-term failure mode in starter motors—when brushes wear down to less than 5mm length, electrical contact becomes intermittent, causing erratic starting performance.

Surrounding the armature, the field assembly creates the stationary magnetic field essential for motor operation. Traditional starters use field coils—thick copper wire wound around iron pole shoes mounted to the inside of the motor housing—energized by the same current flowing through the armature. This series-wound configuration means field strength increases with motor current, producing maximum torque during the high-current initial cranking phase. However, modern designs increasingly use permanent magnets mounted directly to the housing interior, eliminating field coil resistance losses and reducing motor weight by 30-40%. These rare-earth permanent magnets maintain strong, consistent magnetic fields without requiring any electrical power, improving efficiency especially during cold-weather starting when every amp of battery capacity matters.

The motor housing provides structural support while also serving as the magnetic return path for the field flux. Cast from aluminum for light weight with steel mounting flanges for strength, the housing bolts directly to the engine block or transmission bell housing. Precise mounting alignment is critical—if the starter sits even slightly out of position, the pinion gear won’t mesh properly with the flywheel ring gear, causing destructive grinding noises and rapid tooth wear. Ventilation openings in the housing allow cooling air circulation, though starters operate hot by design since they function only in brief bursts rather than continuously.

Solenoid Assembly

Mounted atop or alongside the motor housing, the solenoid performs two essential functions: it mechanically engages the pinion gear with the flywheel, and it acts as a high-current relay completing the electrical circuit to the motor windings. This dual-purpose design emerged as a solution to the fundamental problem of switching the massive current required by the starter motor—no conventional switch could handle 150-300 amps reliably, and running such heavy current through the ignition switch would create dangerous conditions inside the passenger compartment.

The solenoid contains two electromagnetic coils working in tandem: a pull-in coil and a hold-in coil, both wound around a hollow iron core. When the ignition switch closes, battery voltage energizes both coils simultaneously. The pull-in coil connects between the battery terminal and ground through the motor windings, while the hold-in coil connects between the battery terminal and a second terminal that will eventually connect to the motor. Together, these coils generate a powerful magnetic field that pulls an iron plunger rapidly inward against spring pressure. This initial pull-in force must be strong enough to overcome the return spring and push the shift fork mechanism—typical solenoid plungers move 10-15mm in 50-80 milliseconds when energized.

As the plunger reaches full travel, it performs its dual function. First, through a mechanical linkage to the shift fork, it pushes the pinion gear forward along helical splines on the armature shaft until the pinion fully engages with the flywheel ring gear. Second, the plunger’s inward movement brings a large copper contact disc into contact with two heavy terminals—one connected directly to the battery positive cable, the other connected to the motor windings. When this contact disc bridges the terminals, it completes the high-current circuit, sending full battery power to the motor. At this moment, the pull-in coil de-energizes (both its ends now connect to battery positive), and only the hold-in coil continues drawing current to maintain plunger position until the ignition key returns to the run position.

The contact disc and terminals inside the solenoid represent critical wear points. During every starting cycle, these contacts must handle 150-300 amps, causing small amounts of metal to transfer between the surfaces through arcing and resistance heating. Over time, the contact surfaces develop pitting and oxidation, increasing electrical resistance. This degradation manifests as intermittent starting—some attempts produce strong cranking, others result only in a click as the solenoid engages but fails to pass sufficient current through degraded contacts. Professional rebuilders can resurface or replace these contacts, extending solenoid life, though complete starter replacement often proves more cost-effective for modern vehicles.

Drive Mechanism

The drive mechanism faces a challenging task: it must engage the pinion gear with the flywheel smoothly and reliably, transmit high torque during cranking, then disengage instantly when the engine starts to prevent the running engine from over-speeding and destroying the starter motor. Modern pre-engaged starters accomplish this through a sophisticated combination of helical splines, an overrunning clutch, and the solenoid-actuated shift fork.

The pinion gear, machined from hardened steel with 8-12 precisely cut teeth, slides on helical splines machined into the armature shaft. These angled splines serve multiple purposes: they allow the pinion to move linearly toward and away from the flywheel, they provide some rotational compliance during engagement, and they help the pinion teeth find gaps between flywheel teeth if initial contact occurs tooth-to-tooth. When the shift fork pushes the pinion forward and it encounters the flywheel ring gear, any initial misalignment causes the pinion to rotate slightly on the helical splines, allowing the teeth to slip into mesh smoothly rather than clashing destructively.

Between the pinion and the armature shaft, the overrunning clutch provides critical protection once the engine starts. This one-way clutch mechanism—often called a Bendix drive after its inventor—allows torque transmission in only one direction. During cranking, when the starter motor drives the pinion faster than the engine rotates, the clutch locks solid, transmitting full motor torque to the flywheel. However, once the engine fires and begins running under its own power, it quickly accelerates beyond starter motor speed. At this point, the overrunning clutch unlocks, allowing the flywheel to rotate freely without back-driving the starter motor. This protection is essential—without it, if a driver held the ignition key in the start position after the engine fired, the running engine would spin the starter armature at 5,000-10,000 RPM, instantly destroying the motor through centrifugal forces and excessive current generation.

The shift fork, actuated by the solenoid plunger, provides the mechanical connection between the solenoid and the pinion assembly. This forked lever pivots on a pin, with one end connected to the solenoid plunger and the other end fitting into a groove on the overrunning clutch assembly. The geometry of this lever system provides mechanical advantage, amplifying the solenoid plunger force to reliably slide the pinion assembly forward even against resistance from dirt, corrosion, or slight misalignment. Proper shift fork operation requires that the pinion fully engage before the motor begins spinning—pre-engaged starters accomplish this through careful timing built into the solenoid design, ensuring the contact disc closes only after the plunger completes its travel and the pinion reaches full engagement depth.

Understanding these internal components explains common failure modes. Worn brushes cause intermittent contact and weak cranking. Degraded solenoid contacts produce clicking without cranking. A failed overrunning clutch results in freewheeling—the starter spins loudly but doesn’t turn the engine. Broken shift fork prevents pinion engagement entirely. Each component represents a potential failure point, though proper diagnosis can identify the specific fault without requiring complete starter replacement in every case.

The Complete Starting Sequence: Step by Step

The journey from turning your ignition key to hearing your engine roar to life involves a precisely choreographed electrical and mechanical sequence occurring in less than three seconds. Understanding each step of this process reveals the sophisticated coordination between multiple vehicle systems and helps diagnose problems when any step fails to execute properly. Modern starting systems accomplish this complex sequence with remarkable reliability, executing hundreds of thousands of cycles over a vehicle’s lifetime.

Step 1: Ignition Switch Activation

The starting sequence begins when you turn the ignition key to the “start” position or press the engine start button. This action closes a low-current circuit, sending approximately 2-5 amps from the battery through the ignition switch. Before this signal can reach the starter system, it must pass through important safety interlocks. In vehicles with automatic transmissions, the neutral safety switch verifies that the transmission selector is in Park or Neutral before allowing current to flow—this prevents the vehicle from lurching forward or backward if accidentally started in gear. Manual transmission vehicles employ a similar clutch safety switch mounted at the clutch pedal, requiring the clutch to be fully depressed before the starting circuit completes.

These safety switches represent critical protection systems mandated by safety regulations, yet they also serve as common failure points. A misadjusted neutral safety switch may prevent starting even with the transmission correctly positioned, or conversely, allow starting in gear if improperly aligned. Technicians diagnosing intermittent no-start conditions often check these switches early in the diagnostic process, as simple adjustment or replacement can resolve what appears to be a complex electrical problem.

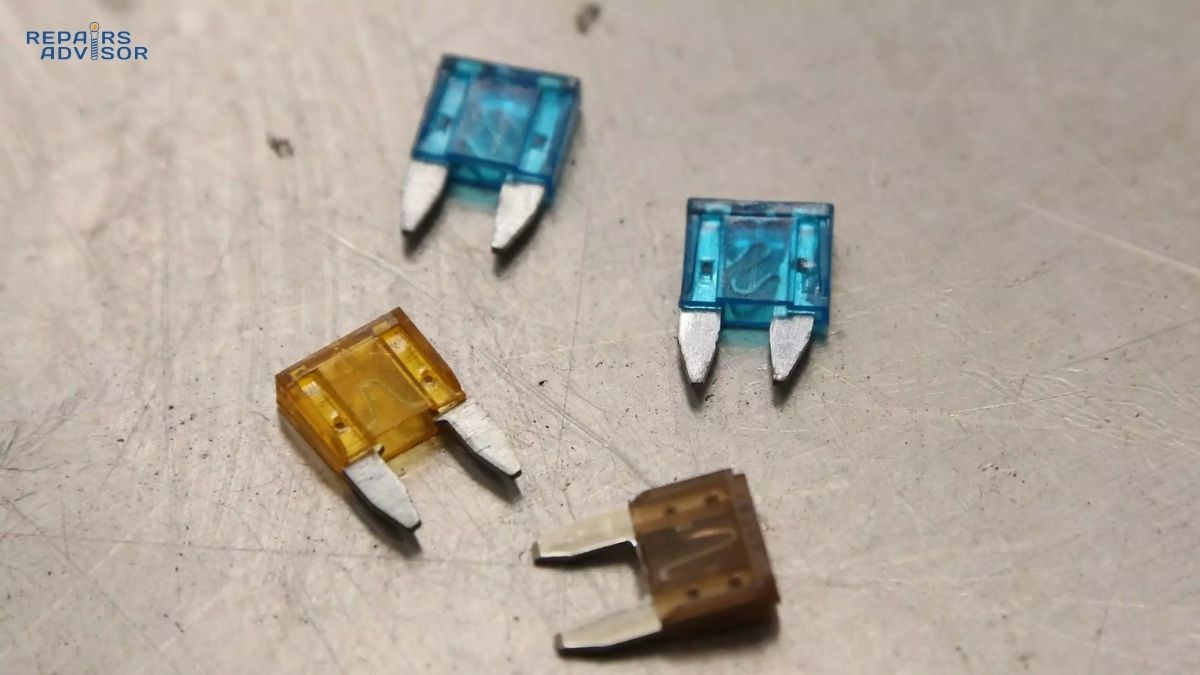

Once the safety switch closes, the low-current signal travels to the starter relay coil. This relay—often located in the under-hood fuse and relay box—serves as an electronic amplifier, using the small control current from the ignition switch to control a much larger current feeding the starter solenoid. The relay design protects the ignition switch from high current and allows the ignition switch wiring to use smaller-gauge wire, reducing cost and improving reliability. Some vehicles integrate additional logic at this stage—anti-theft systems verify the correct key code before energizing the relay, and engine management systems may prevent cranking if certain fault conditions exist.

Step 2: Relay and Solenoid Engagement

When the starter relay energizes, it closes contacts that send full battery voltage to the solenoid control terminal. This voltage energizes both the pull-in and hold-in coils inside the solenoid simultaneously, creating a powerful magnetic field in the iron core. The magnetic force overcomes the return spring pressure and pulls the iron plunger inward with surprising speed—typically completing its 10-15mm travel in just 50-80 milliseconds. The rapid plunger movement is audible as the characteristic “click” heard when starting a vehicle, confirming that the solenoid has received the activation signal and responded mechanically.

The dual-coil design provides optimal performance throughout the engagement cycle. During initial movement, both coils work together to generate maximum magnetic force, ensuring the plunger moves quickly and forcefully. As the plunger nears the end of its travel, the pull-in coil automatically de-energizes (both its terminals now connect to battery positive voltage), leaving only the hold-in coil to maintain plunger position. This design reduces current draw once engagement is achieved while maintaining adequate holding force throughout the cranking period.

Understanding solenoid operation helps diagnose common problems. A single loud click followed by silence indicates the solenoid activated but the motor failed to crank—typically pointing to degraded solenoid contacts, a seized motor, or a dead battery cell. Rapid clicking suggests insufficient current to fully energize the solenoid, usually caused by a weak battery or high-resistance connections. No click at all means the solenoid isn’t receiving the activation signal, directing diagnosis toward the ignition switch, relay, safety switches, or wiring rather than the starter itself.

Step 3: Pinion Gear Engagement

As the solenoid plunger moves inward, it pulls the shift fork through a mechanical linkage. The shift fork, pivoting on its mounting pin, pushes against the overrunning clutch assembly, sliding the entire pinion drive assembly forward along the helical splines on the armature shaft. The pinion gear moves approximately 8-12mm toward the engine, approaching the flywheel ring gear teeth. In an ideal scenario, the pinion teeth align perfectly with gaps between flywheel teeth, allowing smooth engagement as the pinion slides into position.

However, tooth-to-tooth contact frequently occurs—the pinion teeth meet flywheel teeth tip-to-tip rather than finding a gap. In older inertia-type starters, this situation caused harsh grinding as the spinning motor forced engagement. Modern pre-engaged starters handle this elegantly through the helical splines. When tooth-to-tooth contact occurs, the engagement force from the shift fork causes the pinion to rotate slightly on the helical splines, automatically repositioning the teeth until they find a gap and snap into full mesh. This rotation happens quickly—often within one or two degrees—producing only a brief scraping sound rather than sustained grinding.

Proper pinion engagement depth is critical for reliable operation. Too shallow engagement leaves insufficient tooth mesh, causing teeth to skip under load and rapidly wear. Too deep engagement can prevent proper disengagement after starting, potentially causing the running engine to drive the starter motor at destructive speeds. Starter manufacturers carefully design the shift fork geometry, helical spline pitch, and solenoid plunger travel to achieve the optimal 8-12mm engagement depth across a wide range of operating conditions and component wear states.

Step 4: Motor Circuit Completion

After the pinion reaches full engagement, the solenoid plunger continues moving the final few millimeters of its travel. This additional movement brings the internal contact disc into firm contact with both the battery terminal and the motor terminal. At this instant, full battery voltage—typically 12.6 volts at rest—applies directly to the motor windings through a low-resistance path capable of carrying 150-300 amperes. The contact disc, machined from copper for maximum conductivity, must maintain solid contact under the enormous current flow and electromagnetic forces generated during cranking.

The electrical circuit for cranking current follows a simple but high-capacity path: positive current flows from the battery positive terminal through a heavy-gauge cable (typically 4-6 AWG) to the solenoid battery terminal, through the closed contact disc to the motor terminal, through the motor windings (both field coils and armature windings in series for maximum torque), then back to ground through the starter motor housing, engine block, and ground strap to the battery negative terminal.

During cranking, the electrical load causes battery voltage to drop significantly—from 12.6 volts at rest to 10.5-11.5 volts under load is normal for a healthy battery and starting system. This voltage drop results from internal battery resistance and the resistance of all connections in the high-current path. If voltage drops below 9.6 volts during cranking, insufficient energy reaches the starter motor, resulting in slow or failed cranking that suggests either a weak battery or high-resistance connections requiring cleaning or repair.

Step 5: Engine Cranking

With full current flowing through the motor windings, electromagnetic forces between the field magnets and the armature create rotational torque. The armature begins spinning, and the commutator-brush system continuously reverses current direction through the armature windings to maintain rotation. The starter motor typically spins at 3,000-4,000 RPM under no-load conditions, but the 15:1 to 20:1 gear reduction between the pinion and flywheel ring gear translates this to 150-250 RPM at the crankshaft for gasoline engines, or 100-150 RPM for diesel engines with higher compression ratios.

As the engine rotates, each cylinder progresses through its four-stroke cycle: intake, compression, power, and exhaust. The starter motor must overcome varying resistance throughout these cycles—compression strokes create peak resistance as pistons compress air-fuel mixture against closed valves, while intake and exhaust strokes offer less resistance. In a four-cylinder engine, the starter experiences load pulses at approximately 100 Hz at normal cranking speed, creating a characteristic rhythmic sound. Six and eight-cylinder engines produce smoother cranking with more frequent but smaller load variations.

The starter motor must maintain consistent cranking speed through these load variations to ensure reliable starting. When cranking speed drops too low, insufficient air-fuel mixture enters the cylinders, compression pressure falls below the level needed for ignition, and the engine fails to fire. Factors affecting cranking speed include battery capacity and charge state, starter motor condition, engine oil viscosity (particularly in cold weather), and engine mechanical condition. A healthy starting system maintains steady, strong cranking for the 1-3 seconds typically required for a warm engine to start, or 3-5 seconds for cold-start conditions.

Step 6: Engine Start and Disengagement

When the engine fires and begins running under its own power through combustion, engine speed rapidly accelerates beyond the cranking speed provided by the starter motor. Within half a second, the engine typically reaches 800-1,200 RPM—three to six times faster than starter cranking speed. At this point, the overrunning clutch serves its critical protective function. As the flywheel accelerates faster than the pinion gear driving it, the one-way clutch mechanism unlocks, allowing the flywheel to rotate freely without back-driving the starter motor armature. This instantaneous disengagement prevents the running engine from spinning the starter at destructive speeds that would exceed the design limits of the bearings, windings, and commutator.

The driver releases the ignition key from the “start” position back to “run,” de-energizing the starter relay and solenoid coil. The solenoid return spring immediately pushes the plunger back to its rest position. This plunger movement performs two simultaneous actions: it pulls the shift fork backward, sliding the pinion assembly out of mesh with the flywheel ring gear, and it allows the contact disc to separate from the battery and motor terminals, cutting all power to the starter motor. The pinion typically disengages within 100-200 milliseconds after the key releases, though the flywheel inertia and overrunning clutch ensure no damage occurs even if disengagement takes longer.

Modern vehicles often incorporate additional intelligence into the starting sequence. Push-button start systems typically prevent reactivation if the engine is already running, protecting against accidental restarts. Some systems monitor cranking duration and temporarily disable the starter if excessive cranking time suggests a problem requiring diagnosis rather than continued cranking attempts. Hybrid and electric vehicles with internal combustion engines may integrate the starter motor with the hybrid system, using the same electric motor for both starting and regenerative functions.

Understanding this complete sequence enables effective troubleshooting. If the sequence stops at step 1, diagnosis focuses on the ignition switch, safety switches, and control circuit. Failure at step 2 indicates relay or solenoid control circuit problems. Successful steps 1-3 with failure at step 4 points to solenoid contacts or motor issues. Weak performance at step 5 suggests battery, connection, or motor degradation. Each step builds on the previous, creating a logical diagnostic path from simple electrical verification to component-level testing.

Common Starter Motor Problems and Diagnosis

Starter motor problems manifest through distinctive symptoms that, once understood, point directly toward the root cause. Professional diagnosis follows a systematic approach, testing components in order from most likely to least likely failures, from simplest to most complex checks, and from least expensive to most expensive potential repairs. Understanding this diagnostic hierarchy prevents unnecessary part replacement and expensive misdiagnosis—a critical skill since approximately 60% of suspected starter motor failures actually stem from battery or connection problems rather than the starter itself.

Symptom 1: Single Click, No Cranking

When you turn the key and hear a single loud “click” but the engine doesn’t crank, the sound confirms that the solenoid received the activation signal and the plunger moved, but insufficient current reached the motor to produce rotation. This is one of the most common starting complaints, and while it often suggests a failing starter motor, proper diagnosis frequently identifies other causes.

The most common culprit is a weak or dead battery—even if the battery shows adequate voltage at rest (12.4+ volts), internal damage from age, sulfation, or a failed cell can prevent the battery from delivering the high current required during cranking. The 150-300 amp cranking load drops battery voltage from the resting 12.6 volts to approximately 10.5-11.5 volts in a healthy system. If the battery cannot maintain voltage above 9.6 volts under load, insufficient energy reaches the starter motor despite the solenoid successfully engaging.

Diagnostic procedure begins with battery voltage measurement using a multimeter. With the engine off and no loads operating, measure voltage across the battery terminals—a reading below 12.4 volts indicates an undercharged battery requiring charging before further testing. Next, measure voltage at the battery terminals while attempting to start the engine. If voltage drops below 9.6 volts, the battery has failed or lacks sufficient charge. A battery showing 12.6 volts at rest but dropping below 9.6 volts under load has internal damage and requires replacement regardless of its voltage when not loaded.

If battery voltage remains adequate under load but cranking still fails, check voltage at the starter motor battery terminal (the large terminal on the solenoid). With the ignition in the start position, this terminal should show battery voltage—if it doesn’t, the main battery cable has failed, is poorly connected, or is severely corroded. Clean battery terminals and cable ends with a wire brush, ensuring bright metal-to-metal contact, then retest. Inspect ground connections with equal care—the ground circuit completes the electrical path and high resistance in ground connections causes the same symptoms as poor positive connections.

If voltage tests confirm adequate battery capacity and good connections, yet the starter still fails to crank, the problem lies within the starter assembly itself. The most common internal failures producing this symptom are severely worn brushes creating poor electrical contact with the commutator, or degraded solenoid contacts failing to pass current even though the solenoid mechanically engages. In some cases, the motor itself may be seized from internal damage, rust, or debris. Professional rebuilders can often repair these issues by replacing brushes and contacts, though starter replacement frequently proves more cost-effective given labor costs and the availability of quality remanufactured units.

Symptom 2: Rapid Clicking Sound

Rapid clicking—typically 5-10 clicks per second—indicates the solenoid is engaging and disengaging repeatedly in quick succession. This occurs when the initial solenoid engagement draws sufficient current to pull the plunger in, but cranking load immediately drops battery voltage below the threshold needed to maintain solenoid engagement. The solenoid releases, voltage recovers slightly, the solenoid re-engages, and the cycle repeats at a rate determined by the electrical characteristics of the circuit.

This symptom almost always indicates insufficient battery capacity or excessive resistance in the battery cables or connections. A battery weakened by age, cold temperature, or partial discharge may show adequate voltage at rest but cannot deliver the sustained high current required during cranking. The rapid clicking confirms that enough current exists to operate the solenoid (which draws only 10-15 amps) but not enough to spin the motor (requiring 150-300 amps).

Diagnosis follows the same voltage testing procedures described above. Measure battery voltage during the cranking attempt—if it drops rapidly or fluctuates between 8-10 volts, the battery has failed. Cold weather exacerbates this problem, as battery capacity drops approximately 35% at 32°F and 60% at 0°F compared to 80°F capacity. A marginally weak battery might start a vehicle normally in summer but fail completely in winter conditions.

Perform voltage drop testing on both the positive and negative circuits to identify high-resistance connections. Connect a multimeter’s positive lead to the battery positive post and negative lead to the starter motor’s positive terminal (on the solenoid). Have an assistant attempt to start the engine while you observe the voltage reading. Any voltage drop greater than 0.5 volts indicates excessive resistance in the positive circuit—clean and tighten all connections, replace damaged cables, and retest. Repeat this procedure for the ground circuit: connect the multimeter between the battery negative post and the starter motor housing. Voltage drop should be less than 0.3 volts; higher values indicate poor ground connections requiring cleaning or cable replacement.

Corroded battery terminals represent a frequent cause of excessive resistance despite appearing relatively minor. The white, blue, or green corrosion that accumulates on battery posts and cable terminals dramatically increases resistance, preventing adequate current flow. Clean terminals thoroughly with a wire brush and baking soda solution, then apply terminal protector spray to prevent recurrence.

Symptom 3: Grinding or Screeching Noise

Metallic grinding or screeching during starting indicates mechanical interference between the starter pinion gear and the engine’s flywheel ring gear. This troubling sound typically means metal-to-metal contact is occurring under high force and speed, rapidly damaging teeth on both components. If left unaddressed, grinding problems quickly progress from minor noise to complete starting failure as gear teeth wear away or break.

Several causes produce grinding symptoms, each requiring different solutions. Worn or damaged flywheel ring gear teeth—common on high-mileage vehicles that have experienced hundreds of thousands of starts—may have missing or severely worn teeth in specific locations around the flywheel circumference. When the starter pinion attempts to engage in a worn section, teeth clash rather than meshing smoothly. Similarly, worn or broken teeth on the starter pinion itself cause grinding, though pinion wear typically produces more consistent noise rather than the intermittent grinding characteristic of flywheel damage.

Faulty engagement timing represents another common cause. In pre-engaged starters, the solenoid should fully engage the pinion with the flywheel before the motor begins spinning. If the solenoid contact disc closes too early—before the pinion fully meshes—the motor spins the pinion against partially engaged flywheel teeth, causing severe grinding. This timing problem usually stems from worn internal solenoid components or incorrect solenoid adjustment if the starter has been previously repaired or replaced.

Loose starter mounting bolts allow the starter position to shift during engagement, preventing the pinion from aligning properly with the flywheel ring gear. Starter motors mount with two or three bolts typically torqued to 30-50 ft-lbs depending on the vehicle—if these bolts loosen, even slight movement of the starter housing throws off the critical alignment between the pinion and flywheel. Simply tightening the mounting bolts often resolves grinding problems if caught before significant tooth damage occurs.

Diagnosing grinding noises requires visual inspection when possible. Many vehicles provide access to view the flywheel ring gear through the starter mounting hole or a bell housing inspection cover. Rotate the engine by hand (turn the crankshaft pulley bolt with a wrench) while inspecting the flywheel teeth—look for missing teeth, severely worn teeth, or sections with obvious damage. Remove the starter and inspect the pinion gear for similar damage. If both gears appear intact, verify proper starter mounting and check for installation of an incorrect starter motor (using the wrong part number can result in a pinion gear with incorrect dimensions or tooth count).

Symptom 4: Starter Spins But Doesn’t Engage (Freewheeling)

A high-pitched whining or whirring sound when starting—sometimes described as the starter “freewheeling”—indicates the motor spins freely but doesn’t rotate the engine. This failure means the drive mechanism that should connect the motor to the flywheel has failed, preventing torque transmission despite normal motor operation. This symptom demands immediate attention as continued operation provides no starting benefit while accumulating additional wear on the malfunctioning starter.

The overrunning clutch mechanism represents the most common failure point causing freewheeling. This one-way clutch should lock solid when the motor drives the pinion but freewheel when the engine drives the pinion. When the clutch fails internally—typically from worn rollers or springs, or from lubricant contamination—it fails to lock in either direction, allowing the motor to spin without transmitting torque to the pinion and flywheel. Complete clutch failure often occurs suddenly rather than gradually, making it difficult to predict or prevent through maintenance.

A broken or damaged Bendix drive mechanism can produce similar symptoms. If the shift fork breaks, the solenoid plunger movement fails to push the pinion into engagement with the flywheel. The motor receives power and spins normally, but with the pinion remaining retracted, no connection exists to rotate the engine. This failure may produce clicking sounds as the shift fork attempts to move but can’t overcome the broken connection.

Stripped helical splines on the armature shaft prevent the pinion from sliding forward during engagement or transmitting torque during cranking. This damage typically results from repeated forcing of engagement when the pinion and flywheel teeth don’t align properly, gradually wearing away the angled splines until they no longer function.

Diagnosis requires starter removal and bench testing in most cases. With the starter removed from the vehicle, inspect the overrunning clutch operation manually—the pinion should rotate freely in one direction but lock solid in the other direction. Any slippage in the locked direction confirms clutch failure. Connect the starter to a battery for bench testing: the pinion should extend firmly and rotate when power is applied. Observe whether the pinion moves forward before the motor spins (proper solenoid operation) or if the motor spins without pinion movement (shift fork or solenoid failure). Examine the armature shaft splines for wear or damage.

Symptom 5: Slow Cranking

Sluggish cranking—when the starter turns the engine but noticeably slower than normal—often precedes complete starting failure. This progressive symptom provides valuable warning that battery capacity is declining, electrical connections are deteriorating, or the starter motor itself is weakening. Addressing slow cranking immediately can prevent being stranded with a complete no-start condition.

Multiple factors contribute to slow cranking. Marginal battery capacity—common in batteries approaching the end of their 3-5 year service life—reduces the available current for cranking. As batteries age, internal resistance increases and active plate material deteriorates, diminishing both voltage and current delivery capability. Cold weather dramatically accelerates this decline, reducing battery capacity by 35-60% compared to warm weather performance while simultaneously increasing engine oil viscosity and making starting more difficult.

Voltage drop in electrical connections accumulates as terminals corrode and cable ends oxidize. Each high-resistance connection reduces the voltage available to the starter motor. A battery starting at 12.6 volts but dropping to 11.5 volts at the starter motor due to cable resistance provides significantly less power than if the full 12.6 volts reached the motor. Multiple small resistance points—corroded battery posts, loose cable connections, degraded ground straps—combine to create substantial power loss.

Internal starter motor wear increases with accumulated mileage and age. Worn brushes create increasing resistance between the brush faces and commutator segments, reducing current flow through the armature windings. A dirty or oxidized commutator surface compounds this problem. Worn bearings increase friction, requiring more torque just to rotate the armature before any useful work occurs. While these degradations typically develop gradually over 100,000+ miles, they eventually accumulate to produce noticeably slow cranking.

Engine mechanical issues can manifest as slow cranking even with a healthy starting system. Thick oil in cold weather—particularly if the incorrect viscosity is used—dramatically increases engine drag. A 10W-30 oil may flow adequately at 70°F but becomes nearly solid at 0°F, making the engine far more difficult to rotate. More serious problems include seized components, damaged bearings creating excessive drag, or hydro-locking from coolant or fuel accumulation in cylinders.

Diagnostic approach prioritizes electrical system testing before assuming starter or engine problems. Begin with battery voltage measurement at rest and under load. Check the battery’s Cold Cranking Amp (CCA) rating against the manufacturer’s specification—as batteries age, actual CCA falls well below the rating stamped on the case. Many auto parts stores offer free battery testing that measures actual capacity versus rated capacity. Perform voltage drop testing on both positive and negative circuits as described earlier, addressing any connections showing excessive resistance.

Monitor battery voltage at the starter motor terminals during cranking. The voltage should remain above 10.5 volts during cranking for most vehicles (some specifications allow down to 9.6 volts). If adequate voltage reaches the starter but cranking remains slow, the problem likely resides in the starter motor itself or in engine mechanical drag. Assess whether the slow cranking is consistent or varies—intermittent slow cranking suggests poor electrical connections that make inconsistent contact, while consistently slow cranking points toward worn motor components.

Temperature sensitivity provides diagnostic clues. Slow cranking that occurs only in cold weather but disappears in warm conditions suggests inadequate battery capacity for cold-weather demands or incorrect oil viscosity. Conversely, slow cranking that worsens when the engine is hot may indicate starter motor bearing wear or heat-related electrical connection expansion creating poor contact.

Professional Diagnostic Procedures

Professional technicians employ specialized equipment and systematic procedures that provide definitive diagnosis beyond the basic voltage testing available to DIYers. Understanding these professional methods helps you communicate effectively with mechanics and recognize thorough versus superficial diagnostic work.

Voltage drop testing represents the most critical diagnostic procedure for starting system problems. While basic voltage measurement identifies gross battery or connection failures, voltage drop testing reveals subtle resistance issues that prevent optimal system performance. Technicians measure voltage differential between two points while current flows through the circuit—any voltage difference indicates resistance consuming power. On the positive circuit, connect the voltmeter between the battery positive post and the starter positive terminal, then activate the starter. Voltage drop should be less than 0.5 volts; higher readings pinpoint excessive resistance requiring connection cleaning or cable replacement. Repeat for the negative circuit from battery negative post to starter housing—acceptable drop is less than 0.3 volts. This testing precisely identifies which connections or cables require service rather than replacing parts based on guesswork.

Bench testing confirms starter operation outside the vehicle, eliminating variables introduced by the engine, transmission, and vehicle electrical system. After removing the starter, secure it firmly in a vise or on a workbench (standing on it works but poses safety risks if not done correctly—the starter will jump forcefully when energized). Connect heavy jumper cables: positive cable to the starter battery terminal, negative cable to the starter housing. Create a jumper wire to connect the solenoid control terminal to the battery positive. When this connection is made, the starter should perform a complete cycle: the pinion should extend approximately 10-12mm, the motor should spin strongly at 3,000+ RPM no-load speed, and the pinion should rotate. Observe that pinion extension occurs before the motor begins spinning—if they occur simultaneously or the motor spins without pinion extension, the solenoid requires replacement. Measure no-load current draw: typical starters consume 60-100 amps spinning freely with no load. Excessive current suggests internal motor problems.

Current draw testing during actual cranking quantifies starter motor electrical consumption and can identify problems not apparent from voltage testing alone. Professional technicians use an inductive ammeter clamped around the battery positive cable to measure current flow during cranking without breaking the circuit. Normal current draw during cranking ranges from 150-250 amps for most vehicles, though specifications vary. High current draw (300+ amps) combined with slow cranking indicates internal motor problems such as partially shorted windings, dragging bearings, or internal damage creating excessive friction. High current with normal cranking speed suggests engine mechanical problems—excessive internal friction or compression issues making the engine abnormally difficult to rotate. Low current draw (below 100 amps) combined with slow or no cranking points to high resistance somewhere in the circuit preventing current flow, or severely worn brushes in the starter motor creating poor electrical contact.

These professional diagnostic procedures definitively identify whether problems reside in the battery, cables and connections, starter motor, or engine mechanical system. When paying for professional diagnosis, expect technicians to perform these tests systematically rather than simply replacing the starter based on symptom description alone. Quality diagnosis may cost $100-150 in labor but saves hundreds in unnecessary parts replacement and prevents repeat failures from unaddressed root causes.

Maintenance, Replacement, and Professional Service

Starter motor longevity depends far more on proper electrical system maintenance and operating practices than on any service performed directly on the starter itself. Since starters are sealed units without user-serviceable internal components, preventive care focuses on ensuring the electrical environment supporting starter operation remains optimal throughout the vehicle’s service life. Understanding when DIY replacement is feasible versus when professional service provides better value requires realistic assessment of mechanical skill, tool availability, and vehicle-specific access challenges.

Electrical System Care for Starter Longevity

The starting system’s reliability directly correlates with battery health and connection quality. Clean battery terminals and cable ends represent the single most effective maintenance for preventing starting problems. Inspect terminals every six months, looking for white, blue, or green corrosion accumulating around the posts and cable clamps. Clean terminals thoroughly using a wire brush and a solution of baking soda dissolved in water (one tablespoon per cup), which neutralizes battery acid and dissolves corrosion. Rinse with clean water, dry completely, then apply terminal protector spray or dielectric grease to prevent corrosion recurrence. This simple 15-minute service prevents the majority of “weak starter” complaints that actually stem from corroded connections.

Battery state of charge maintenance extends both battery and starter life. Chronic undercharging—common in vehicles driven only short distances or equipped with aftermarket electronics—forces the starter to draw current from a partially discharged battery. Since a discharged battery has higher internal resistance, the starter must work harder and draws higher current to achieve the same cranking speed, accelerating wear on brushes, commutator, and solenoid contacts. Ensure the charging system maintains battery voltage at 13.8-14.4 volts while driving. If short trips prevent adequate charging, consider connecting a battery maintainer when the vehicle sits for extended periods, or take occasional longer drives to fully recharge the battery.

Cold weather preparedness dramatically affects starting system stress. Cold batteries deliver 35% less capacity at 32°F and 60% less at 0°F compared to their rated capacity at 80°F, while cold engine oil creates substantially higher cranking resistance. This double challenge means winter starting requires far more from the starting system than summer operation. Test battery capacity before winter arrives—batteries showing marginal summer performance will fail completely when temperatures drop. Consider battery replacement if capacity tests reveal less than 70% of rated CCA, rather than waiting for failure. Ensure the correct oil viscosity for climate conditions: 5W-30 flows far better than 10W-30 in cold weather, reducing starter load during cranking.

Operating Practices That Extend Starter Life

Cranking technique significantly impacts starter longevity. The cardinal rule: limit cranking attempts to 10-15 seconds maximum, with 30-60 second cooling periods between attempts. Continuous cranking generates tremendous heat in the motor windings, brushes, and solenoid contacts. The starter motor design optimizes for brief, intermittent operation rather than sustained running—internal components lack the cooling capacity needed for extended operation. Exceeding the 15-second limit risks overheating the motor windings, which can damage insulation and create shorted turns that permanently reduce motor performance. Heat also accelerates brush wear and causes solenoid contacts to arc and pit.

If an engine requires more than three 15-second cranking attempts, stop and diagnose why it won’t start rather than continuing to crank. Persistent cranking when the engine has a fuel, ignition, or mechanical problem serves no purpose except damaging the starter motor and depleting the battery. Modern vehicles with extensive electronics may suffer computer damage from the voltage fluctuations created by extended cranking periods. Professional diagnosis of no-start conditions prevents unnecessary starter damage while addressing the actual problem preventing engine operation.

Never engage the starter while the engine is running. While modern vehicles incorporate automatic prevention systems that disable the starter if the engine is running, older vehicles rely on driver attention. Attempting to start a running engine back-drives the starter through the engaged pinion gear, spinning the armature at 5,000-10,000 RPM—well beyond its design speed and guaranteed to destroy bearings, windings, and the commutator within seconds. The horrific grinding noise this creates is your last warning before complete starter destruction.

When to Replace Versus Rebuild

Starter motors typically provide reliable service for 100,000-150,000 miles under normal conditions, though severe-duty applications (frequent starts, extreme temperatures, high-vibration environments) may shorten service life to 75,000-100,000 miles. Several factors indicate starter replacement is necessary or advisable:

Failed solenoid represents a common failure mode around 100,000 miles as the internal contacts wear from hundreds of thousands of engagement cycles. While solenoids are technically rebuildable by replacing the contact disc and terminals, the labor cost often exceeds the price difference between a replacement solenoid and a complete remanufactured starter assembly. For this reason, technicians frequently recommend complete starter replacement when the solenoid fails.

Worn brushes indicate a starter approaching end of life. When brushes wear to less than 5mm length, electrical contact becomes intermittent and unreliable. While brush replacement is straightforward on older field-coil starters, many modern permanent-magnet starters use brushes that require significant disassembly to access, making professional replacement labor-intensive. Brush wear typically occurs around 120,000-150,000 miles, by which time other starter components have also accumulated significant wear. Complete replacement rather than brush replacement alone often proves more cost-effective and reliable long-term.

Damaged pinion or overrunning clutch generally cannot be economically repaired. These components wear from mechanical stress during thousands of engagement cycles. When gear teeth show significant wear, chips, or missing teeth, the entire drive assembly requires replacement. Similarly, a failed overrunning clutch necessitates drive assembly replacement. While these components are available separately for professional rebuilders, the specialized tools and expertise required make DIY replacement impractical.

Professional rebuilding makes economic sense primarily for heavy-duty starters used in diesel engines, commercial trucks, or equipment where original equipment starters cost $500-1,000+. Professional rebuilders completely disassemble the starter, clean all components, replace worn parts (brushes, bearings, solenoid contacts, drive assembly), test extensively, and warrant their work. Rebuilt starter cost typically runs 40-60% of new starter price while delivering comparable reliability. However, for most passenger vehicles where remanufactured starters cost $100-200, professional rebuilding offers minimal savings over replacement.

DIY Replacement Considerations

Starter replacement difficulty varies dramatically by vehicle design. Some vehicles provide excellent starter access requiring only basic tools and 30-60 minutes for replacement. Others mount the starter in nearly inaccessible locations requiring removal of intake manifolds, exhaust components, or suspension parts, making professional service the practical choice.

Easy access vehicles typically include rear-wheel-drive configurations with the starter mounted low on the driver’s side of the engine, accessible from underneath. Many pickup trucks and older vehicles fall into this category. Required tools include basic socket sets, wrenches, wire brushes for cleaning connections, jack stands for safe vehicle support, and safety glasses. The replacement process involves disconnecting the battery negative cable, accessing the starter from underneath, photographing or sketching wire connections, removing the battery and control wire connections, unbolting the starter (typically 2-3 bolts), and reversing the process with the new starter. Proper torque on mounting bolts (30-50 ft-lbs depending on vehicle) is critical for preventing the grinding noise that results from loose mounting.

Intermediate difficulty vehicles include many modern front-wheel-drive configurations with transverse-mounted engines. Access may require removing the front wheel, inner fender liner, or working from above through the engine bay. These replacements demand mechanical aptitude, proper jack stand usage, and often require following vehicle-specific procedures to access hidden mounting bolts. Intermediate skills may suffice with thorough research and careful work, though professional service provides value if access proves more difficult than anticipated.

Professional service recommended applies to vehicles requiring intake manifold removal, vehicles with complex all-wheel-drive systems where the starter mounts in the valley between cylinder banks, or any situation where critical systems must be disturbed to access the starter. The risk of damaging expensive components during access exceeds the savings from DIY replacement. Additionally, vehicles with complex computer-controlled starting systems may require programming or adaptation procedures after starter replacement—work requiring professional scan tools and technical information.

Professional Service Benefits

Professional starting system service delivers several advantages beyond simple part replacement. Proper diagnosis prevents unnecessary starter replacement when battery, cables, or connections actually cause starting problems. Professional technicians perform the voltage drop testing, current draw measurement, and bench testing described earlier, definitively identifying the failed component. This diagnostic thoroughness prevents the frustration of replacing a starter only to find the starting problem persists because the actual cause—corroded cable connections or a failing battery—remains unaddressed.

Access to Original Equipment specifications ensures correct part selection. Starters are not interchangeable—vehicles require specific parts matched to engine size, compression ratio, and electrical system design. Professional technicians verify part numbers and specifications, preventing installation of incorrect starters that may fit physically but lack adequate capacity or have incompatible pinion gears. They also access service information regarding required adaptation procedures, programming, or learned values that must be reset after starter replacement on computer-controlled vehicles.

Warranty protection provides peace of mind and financial protection. Reputable shops warranty both parts and labor, typically for 12-36 months depending on whether Original Equipment or aftermarket parts are installed. If the replacement starter fails during the warranty period, both the part and the labor to install a replacement are covered. DIY replacement warranties cover only the part itself—if the part fails, you purchase a replacement part but still perform the labor again yourself.

Electrical system verification as part of professional service confirms overall starting system health. Quality technicians check battery capacity, charging system output voltage, and connection quality even when replacing a genuinely failed starter. This comprehensive approach identifies marginal components that, while not currently failed, will likely fail soon—addressing them during the starter replacement visit prevents additional service visits and potential being stranded.

The decision between DIY and professional service ultimately depends on mechanical skill, tool availability, vehicle-specific access difficulty, and personal time value. For straightforward replacements on accessible vehicles, DIY work can save $100-200 in labor costs. For difficult access vehicles or uncertain diagnoses, professional service delivers better value and prevents potentially expensive mistakes.

Conclusion

The starter motor represents one of the most electrically demanding and mechanically stressed components in modern vehicles, converting 12-volt battery power into the high-torque rotation necessary to initiate engine combustion. Understanding the electromagnetic principles driving starter operation—from the series-wound motor design maximizing starting torque, through the solenoid’s dual function of mechanical engagement and high-current switching, to the protective overrunning clutch preventing engine back-drive—transforms mysterious no-start situations into diagnosable problems with logical solutions.

Most starting system failures originate not in the starter motor itself but in supporting components: weak batteries unable to deliver adequate current, corroded connections creating voltage drop, or degraded cables increasing circuit resistance. Systematic diagnosis using voltage testing, voltage drop measurement, and current draw analysis identifies the actual failure point, preventing unnecessary starter replacement while addressing the root cause. When genuine starter motor failure occurs—typically after 100,000-150,000 miles of service—symptoms like grinding noises, freewheeling, or single clicks point toward specific component failures within the starter assembly.

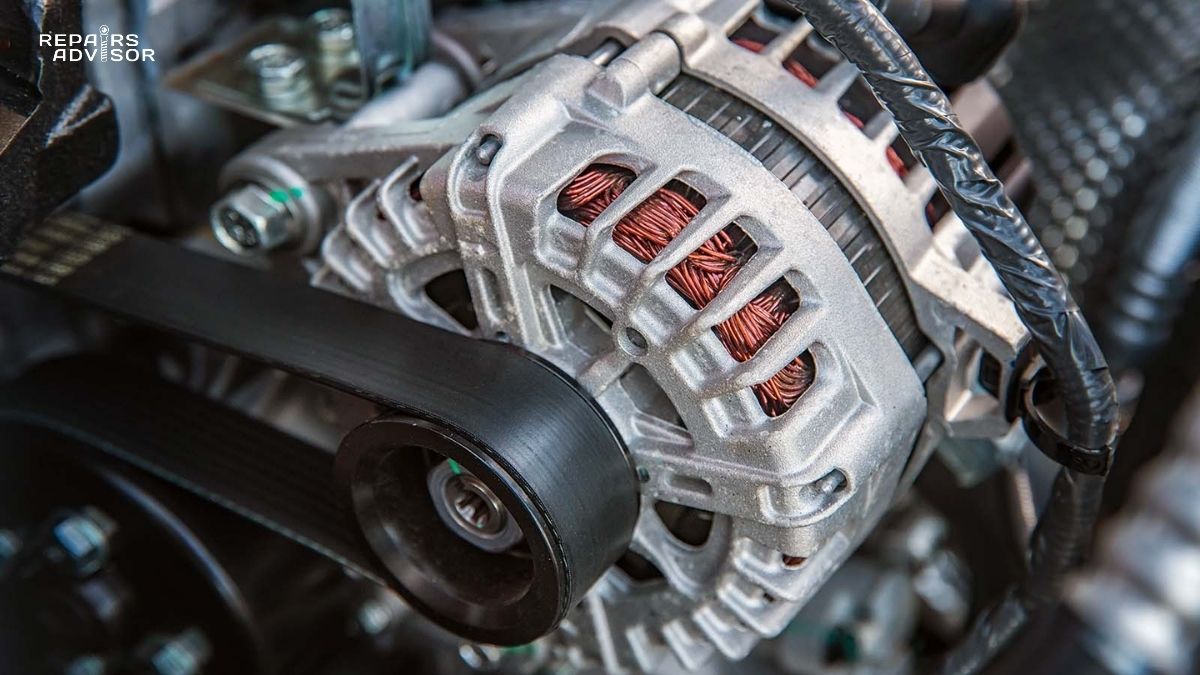

Preventive maintenance focusing on battery health and connection cleanliness provides the best protection against starting system problems. Clean battery terminals every six months, ensure proper battery charging through the alternator, limit cranking to brief intervals with adequate cooling between attempts, and address slow cranking immediately rather than waiting for complete failure. These simple practices extend starter life and prevent the inconvenience and expense of being stranded by starting system failure.

Whether you choose to diagnose and repair starting problems yourself or entrust the work to professional technicians, understanding how starter motors work empowers you to make informed decisions, communicate effectively about symptoms and needed repairs, and recognize when diagnosis is thorough versus superficial. The starting system may operate for just a few seconds each time you drive, but those seconds determine whether your vehicle serves reliably or leaves you stranded—making starter motor knowledge an essential part of automotive literacy for any vehicle owner.

For more information on related electrical systems, explore our guides on how car batteries work, how alternators generate charging power, and how ignition systems create the spark for combustion. You can also find vehicle-specific repair procedures in our comprehensive brand manual collections for Ford, Toyota, Chevrolet, and over 1,000 other equipment manufacturers.