If you’ve driven any modern car built in the last few decades, chances are you’ve experienced MacPherson strut suspension in action. This ingenious design appears in roughly 80% of today’s vehicles, from budget-friendly economy cars to high-performance sports machines like the Porsche 911 and BMW M3. But what makes this 80-year-old suspension system so enduringly popular?

The MacPherson strut represents one of automotive engineering’s most successful compromises—balancing performance, cost, and packaging efficiency in a way that few other designs can match. Named after American engineer Earle S. MacPherson, who developed it in 1945 for General Motors’ post-war economy car projects, this suspension system revolutionized how manufacturers approach front suspension design.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore how MacPherson struts work, examine their core components, compare their advantages and limitations against other suspension types, and help you understand when they need maintenance. Whether you’re a DIY enthusiast looking to tackle your own suspension work or simply want to better understand your vehicle’s handling characteristics, this guide covers everything you need to know about how your car’s suspension works with MacPherson struts.

What is a MacPherson Strut?

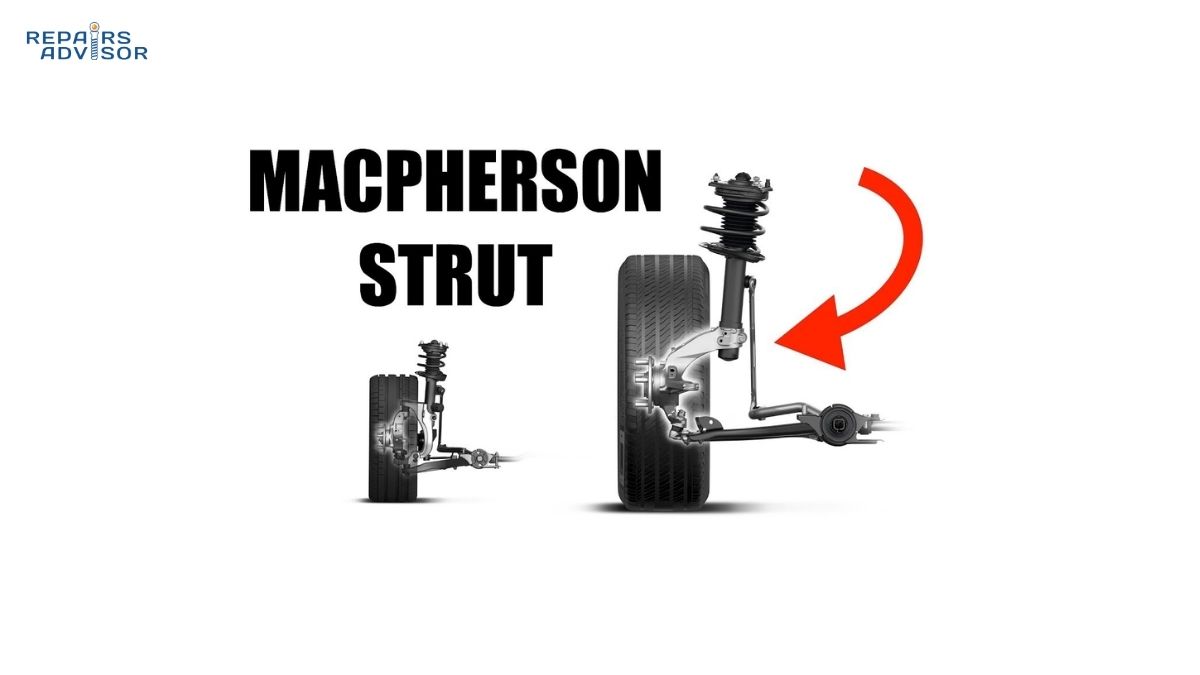

A MacPherson strut is an independent suspension system that combines a shock absorber and coil spring into a single structural unit. Unlike traditional suspension designs that separate these functions, the MacPherson strut integrates damping and spring support while simultaneously serving as part of the steering system—a uniquely efficient approach that distinguishes it from other suspension architectures.

The system’s defining characteristic is that the telescopic damper (shock absorber) itself acts as the upper steering pivot. This eliminates the need for an upper control arm that you’d find in double wishbone suspensions, creating significant space savings in the engine compartment—a crucial advantage for modern transverse-engine, front-wheel-drive vehicles.

Historical Development

Earle S. MacPherson developed this suspension design while working as chief engineer on General Motors’ Chevrolet Light Car project in 1945. His task was to create an affordable, compact vehicle for the post-World War II market, which led to the innovative Chevrolet Cadet prototype. Though GM ultimately cancelled the Cadet project in 1947, MacPherson took his revolutionary suspension design to Ford, where it first appeared in production on the 1950 Ford Consul and Zephyr models in the United Kingdom.

The timing proved perfect. As the automotive industry shifted from body-on-frame construction to unibody (monocoque) designs, the MacPherson strut found its ideal application. Unibody construction provides the strong upper mounting points that struts require while distributing suspension stresses throughout the chassis structure—a match made in engineering heaven.

Today, the MacPherson strut dominates front suspension applications worldwide, chosen by manufacturers for vehicles ranging from the humble Toyota Corolla to the track-focused Honda Civic Type R. Its continued success speaks to the fundamental soundness of MacPherson’s original concept.

Core Components Explained

Understanding how MacPherson struts work requires familiarity with the system’s key components. Let’s examine each part and its specific role in the suspension assembly.

The Strut Assembly

The heart of the system is the strut assembly itself, which combines several critical components into one integrated unit:

Strut Body and Damper: The main cylindrical housing contains a pressurized gas shock absorber that controls suspension movement. Inside, a piston moves through hydraulic fluid, converting kinetic energy from suspension motion into heat energy that dissipates through the strut body. This damping action prevents the coil spring from bouncing endlessly after hitting a bump, maintaining tire contact with the road surface. Most modern struts use pressurized gas (typically nitrogen) in addition to hydraulic fluid to prevent foaming and maintain consistent damping across temperature ranges.

Coil Spring: Wrapped around the strut body, the coil spring absorbs impact energy from road irregularities and supports the vehicle’s weight. Spring rates typically range from 20-40 N/mm (newtons per millimeter) for passenger cars, carefully calculated to balance ride comfort with handling stability. The spring compresses when the wheel encounters a bump, storing energy that’s then released in a controlled manner as the damper moderates its rebound motion.

Upper Strut Mount: This crucial component bolts to the vehicle’s chassis or strut tower and incorporates a bearing plate that allows the entire strut assembly to rotate during steering inputs. The bearing must be low-friction yet durable enough to handle thousands of steering cycles while simultaneously supporting the vehicle’s weight and absorbing road shocks. Rubber isolators in the mount help dampen noise and vibration transfer from the suspension to the passenger compartment.

Spring Seats: Upper and lower spring seats provide mounting surfaces for the coil spring. The lower seat typically welds to the strut body, while the upper seat attaches to the piston rod above the strut mount bearing. Proper alignment of these seats ensures the spring operates along its intended axis, preventing side-loading that could cause premature wear.

Dust Boot and Bump Stop: A rubber or neoprene dust boot covers the piston rod, keeping contaminants out of the strut’s internal seals. The bump stop—a progressive-rate polyurethane cushion—limits suspension travel during extreme compression, preventing metal-to-metal contact that could damage components. Quality shock absorbers and struts incorporate these protective elements as standard features.

Supporting Components

While the strut assembly handles vertical motion and steering pivot duties, several additional components complete the MacPherson strut suspension system:

Lower Control Arm: MacPherson strut systems use a single lower control arm (also called an A-arm or wishbone due to its shape) that connects the wheel hub assembly to the vehicle’s chassis. This arm can take various forms—some manufacturers use a single A-shaped stamping, while others employ an L-shaped design or even a two-piece construction with a compression link and lateral link. The control arm’s mounting points and geometry significantly influence suspension characteristics, including roll center height and anti-dive properties during braking.

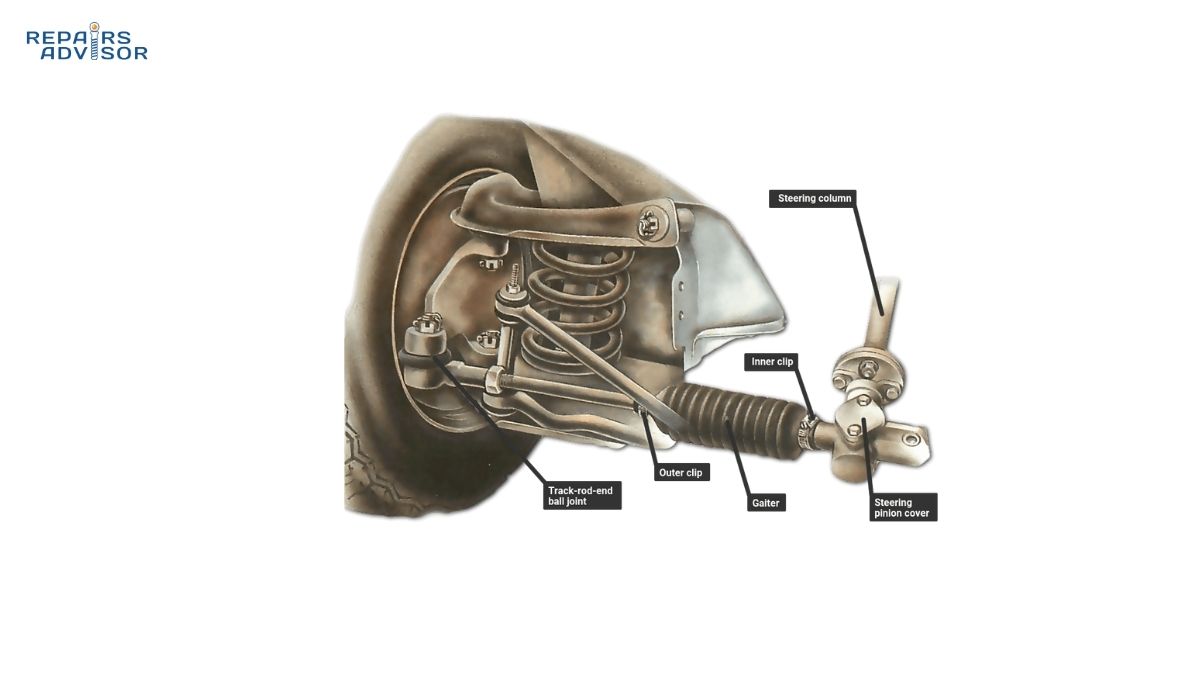

Ball Joint: At the outer end of the control arm, a ball joint provides the pivot point connecting to the steering knuckle. This spherical bearing allows multi-axis rotation, accommodating both suspension travel and steering motion. Modern ball joints typically feature a spring-loaded design with either greaseable fittings or sealed-for-life construction. The ball joint experiences substantial forces during cornering and braking, making it a critical safety component that requires periodic inspection.

Steering Knuckle: The steering knuckle (also called the upright or spindle) is the structural hub that everything connects to. It bolts to the bottom of the strut assembly, connects to the control arm via the ball joint, accepts the tie rod end for steering input, and provides mounting surfaces for the brake caliper and wheel hub bearing. This cast or forged component must withstand enormous multi-directional forces while maintaining precise geometry.

Anti-Roll Bar Link: Many MacPherson strut applications include an anti-roll bar (sway bar or stabilizer bar) connected to the strut via a short link rod with ball joints or bushings on each end. This connection transfers cornering forces from one side of the vehicle to the other, reducing body roll and improving handling response. The link represents a common wear item, with worn bushings or ball joints producing distinctive clunking noises over bumps.

Component Specifications for the Technical Enthusiast

For those interested in the engineering details, MacPherson strut systems operate within specific performance parameters:

- Damping Force Range: 1,000-3,000 N (newtons) for compression and rebound cycles, varying with piston velocity

- Spring Rates: Passenger cars typically use 20-40 N/mm; performance applications may exceed 60 N/mm

- Upper Mount Bearing: Designed for 40-60 degrees of rotation with minimal friction (typically <2 Nm)

- Material Selection: High-strength steel for strut tubes (often chrome-plated), alloyed spring steel for coils, rubber or polyurethane for bushings and mounts

Understanding these specifications helps when selecting replacement components or upgrading suspension performance. Suspension springs with different rates can dramatically alter vehicle characteristics, though matching spring rates to damper valving remains critical for optimal performance.

How MacPherson Struts Work

The beauty of the MacPherson strut lies in its elegant simplicity, but that doesn’t mean the physics are basic. Let’s examine how these systems manage the complex task of maintaining tire contact with the road while providing acceptable ride comfort and responsive handling.

Basic Operating Principles

When your vehicle encounters a bump or pothole, here’s what happens in the fraction of a second it takes to absorb that impact:

Step 1: Impact Absorption – The wheel hits the irregularity, and the coil spring begins compressing. The spring absorbs the kinetic energy from the road disturbance, converting it into potential energy stored in the compressed coils. This prevents the full force of the impact from transmitting directly to the vehicle body and passengers.

Step 2: Damping Control – As the spring compresses, the shock absorber inside the strut works to control the rate of compression. Without damping, the spring would compress rapidly then rebound with equal force, causing the car to bounce endlessly. The damper’s piston forces hydraulic fluid through precisely calibrated orifices, converting kinetic energy into heat that dissipates through the strut body. This controlled motion keeps the tire planted on the road surface.

Step 3: Rebound Management – After the wheel clears the bump, the compressed spring pushes back, extending the suspension. The damper again controls this motion—typically with different valving for rebound than compression—ensuring the wheel returns to its normal position smoothly without overshooting.

Step 4: Stabilization – The upper strut mount’s rubber isolators absorb high-frequency vibrations, preventing harshness from reaching the passenger compartment while the bearing plate allows the strut to pivot freely during steering inputs.

Suspension Geometry and Handling Characteristics

For the technically inclined, MacPherson strut geometry involves several important concepts that affect vehicle handling:

Steering Axis Inclination (SAI): An imaginary line drawn from the upper strut mount through the lower ball joint creates the steering axis. This line typically tilts inward toward the vehicle’s centerline at the top, creating the SAI angle (usually 12-18 degrees). This angle generates self-centering forces that help the steering wheel return to straight-ahead after corners and provides directional stability.

Camber Control: Here’s where MacPherson struts show their primary limitation. Geometric analysis reveals that the system cannot allow vertical wheel movement without some degree of camber change, lateral movement, or both. As the suspension compresses (during cornering or over bumps), the wheel typically gains positive camber—leaning outward at the top. This reduces the tire’s contact patch during the very moments when you need maximum grip.

Double wishbone and multi-link suspensions offer more freedom to engineer camber curves, allowing designers to minimize or even create negative camber gain during compression. This represents the MacPherson strut’s biggest performance compromise, though clever engineers can mitigate these effects through careful geometry optimization and steering geometry tuning.

Scrub Radius: The horizontal distance between where the steering axis intersects the ground and the center of the tire contact patch is called scrub radius. Most MacPherson strut designs produce positive scrub radius, where the steering axis falls inside the contact patch center. While this provides some benefits for straight-line stability, it can contribute to torque steer in high-powered front-wheel-drive vehicles—the tendency for the car to pull to one side under hard acceleration.

Load Path Distribution

Understanding how forces flow through the suspension helps explain component failures and maintenance needs:

Vertical Loads: Vehicle weight and vertical road inputs travel through the coil spring, into the upper strut mount, and directly into the chassis. The strut body itself becomes a structural member, unlike a traditional shock absorber that merely dampens motion. This is why MacPherson struts require robust upper mounting points and why rust or damage to strut towers represents a serious structural issue.

Longitudinal Forces: Braking and acceleration forces transfer primarily through the control arm into its chassis mounting points via bushings that provide compliance for ride comfort while maintaining geometric control. The strut assembly sees some fore-aft loading but relies on the control arm for primary longitudinal location.

Lateral Forces: Cornering generates substantial side loads that both the strut assembly and control arm must resist. The strut experiences bending loads in addition to its primary vertical forces—a key reason why strut bodies use high-strength materials and why performance applications sometimes employ larger-diameter strut tubes or inverted monotube designs for increased rigidity.

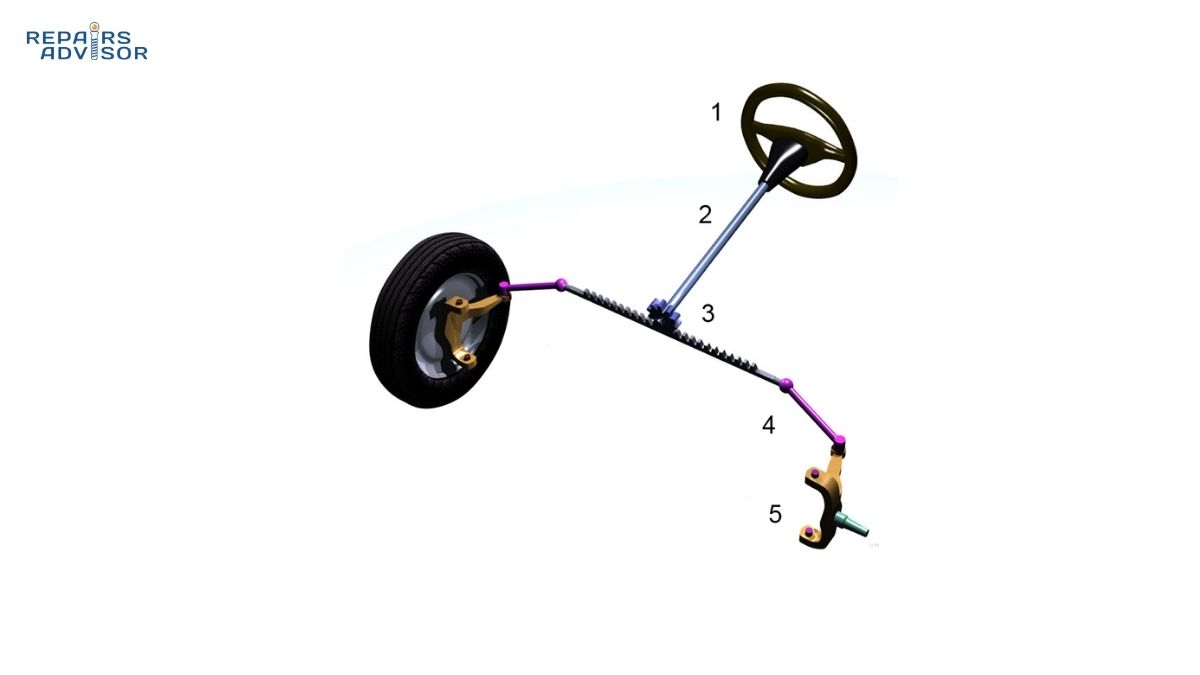

Steering System Integration

One of the MacPherson strut’s cleverest aspects is how it incorporates steering function without additional complexity. When you turn the steering wheel, the steering rack pushes or pulls on the tie rod, which connects to the steering knuckle. The entire strut assembly—from upper mount to lower ball joint—rotates with the knuckle, pivoting on the upper mount’s bearing.

This direct connection provides crisp steering response and good road feel. The upper bearing must accommodate this rotational motion thousands of times daily while simultaneously handling vertical suspension loads and isolating vibration. When this bearing wears—often after 100,000+ miles—drivers notice a clunking sound when turning or a notchy, uneven feeling in the steering wheel.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Like any engineering solution, MacPherson strut suspension involves tradeoffs. Understanding these helps explain why manufacturers choose struts for some applications while other vehicles demand more complex suspension architectures.

Key Advantages: Why Manufacturers Love MacPherson Struts

Exceptional Cost-Effectiveness

The MacPherson strut’s parts count tells much of the story. Where a double wishbone suspension requires upper and lower control arms, upper and lower ball joints, separate shock absorbers and springs, plus associated mounting hardware, the MacPherson design consolidates these functions into fewer components. Manufacturing cost reductions of 30-40% are typical compared to more complex suspension types.

This cost advantage extends beyond initial production. Fewer components mean fewer potential failure points and simpler service procedures. When a MacPherson strut suspension needs attention, many DIY enthusiasts can handle the work with basic tools—though proper spring compression equipment and post-repair alignment remain critical.

Remarkable Space Efficiency

The MacPherson strut’s tall, narrow profile leaves valuable horizontal space in the engine compartment. This advantage became crucial as manufacturers shifted to transverse-engine layouts for front-wheel-drive vehicles. The compact packaging allows larger engines in smaller chassis, or alternatively, provides room for additional components like turbochargers, intercoolers, or hybrid system batteries.

This vertical orientation also enables lower hood lines for improved aerodynamics and styling. Sports car designers appreciate how MacPherson struts help achieve aggressive, low-nose profiles without compromising suspension geometry the way that long, shallow double wishbone arms might.

Meaningful Weight Reduction

Unsprung weight—the mass of components that move with the wheel rather than the sprung chassis—critically affects handling response and ride quality. Lower unsprung weight allows suspension to react more quickly to road irregularities and reduces the energy required to change wheel motion during acceleration, braking, or cornering.

MacPherson struts typically save 5-8 kg (11-18 lbs) per corner compared to double wishbone systems. Over four corners, that’s 20-32 kg of weight savings, mostly unsprung mass. This contributes to better fuel efficiency, quicker steering response, and improved ride quality over rough surfaces.

Proven Performance Track Record

Perhaps the most compelling argument for MacPherson struts is their success in demanding applications. The suspension architecture appears in legendary sports cars including virtually every Porsche 911 built from 1964 through today (except the latest GT3), every generation of the BMW M3, the Honda Civic Type R, Mazda Miata (front suspension), Toyota GR86, and countless other performance vehicles.

If MacPherson struts were fundamentally inferior for performance applications, these manufacturers wouldn’t choose them. The reality is that with proper engineering—optimized geometry, carefully matched spring rates and damping, appropriate chassis stiffness—MacPherson strut suspension delivers excellent handling for the vast majority of driving scenarios.

Primary Disadvantages: Where MacPherson Struts Show Limitations

Limited Suspension Tuning Flexibility

Suspension engineers working with MacPherson struts have less freedom to independently optimize camber curves, roll centers, and anti-dive/anti-squat characteristics compared to multi-link or double wishbone designs. The system’s geometry is largely dictated by the need to place the upper mount near the chassis structure and the lower control arm’s packaging constraints.

This limitation rarely matters for street driving but becomes significant in extreme motorsports applications where maximizing tire contact patch through corners provides measurable performance advantages. It’s why purpose-built race cars typically use double wishbone or multi-link suspensions when regulations permit.

Inherent Camber Change Characteristics

As discussed in the geometry section, MacPherson struts produce unavoidable camber changes during suspension travel. The typical result is positive camber gain during compression—the wheel leans outward at the top when the suspension is compressed, exactly when you’d prefer negative camber for cornering grip.

Modern MacPherson strut designs mitigate this through clever geometry optimization, but they can’t eliminate it entirely. For street use with moderate performance tires and normal cornering forces, this rarely presents practical limitations. Track enthusiasts pushing cars to the limit might notice the difference compared to better-optimized suspension architectures.

Structural and Packaging Requirements

The MacPherson strut’s vertical orientation requires specific chassis design considerations:

- Strong upper mounting points capable of handling multi-directional loads

- Adequate vertical space above the wheel, which can raise the vehicle’s center of gravity slightly

- Unibody construction for proper load distribution (body-on-frame vehicles need modified designs)

These requirements are why you’ll never see true MacPherson struts on full-frame pickup trucks or traditional SUVs. These vehicles use modified strut designs that add an upper control arm, essentially creating a hybrid between MacPherson and double wishbone architectures.

Torque Steer Susceptibility in High-Power FWD Applications

The positive scrub radius inherent in most MacPherson strut geometries can cause torque steer—uneven pulling during hard acceleration—in powerful front-wheel-drive vehicles. When one front wheel experiences more or less grip than the other, the resulting forces pull the steering wheel toward one side.

Modern manufacturers have developed innovative solutions. General Motors’ Hi-Per Strut design and Ford’s Revoknuckle system separate the strut’s structural function from its steering geometry, allowing engineers to optimize both independently. These advanced designs maintain MacPherson strut efficiency while addressing traditional limitations.

MacPherson Strut Variations and Innovations

While Earle MacPherson’s original concept remains fundamentally unchanged, engineers have developed several variations to address specific applications and overcome the design’s inherent limitations.

Modified MacPherson Strut

Body-on-frame vehicles like pickup trucks and traditional SUVs can’t use true MacPherson struts because they lack the strong upper mounting points that unibody construction provides. The modified MacPherson strut adapts the concept for these applications by adding an upper control arm and ball joint while retaining the combined shock/spring strut assembly.

This modification sacrifices some of the MacPherson design’s simplicity and cost advantages but maintains better packaging efficiency than fully separate components. You’ll find modified MacPherson struts on vehicles like the Ford F-150 (earlier generations), Chevrolet Suburban, and similar body-on-frame trucks.

Modern Performance Variations

Hi-Per Strut (General Motors): Introduced on the 2008 Cadillac CTS, this design splits the traditional MacPherson strut into two components. A separate knuckle and steering axis handle steering geometry independently from the spring/damper strut unit. This allows engineers to optimize contact patch geometry and minimize torque steer while maintaining packaging efficiency. The system appeared on several GM performance sedans including the Cadillac ATS-V.

Revoknuckle (Ford): Ford’s solution to torque steer challenges separates the strut from the steering knuckle’s pivot point using a unique design that isolates lateral forces from the damper. First appearing on the 2010 Ford Mondeo ST and later on the Focus RS, this innovation allows high-power front-wheel-drive vehicles to put down serious power without the steering wheel tugging out of your hands.

Honda Dual-Axis Strut: Developed for the Civic Type R, Honda’s adaptation optimizes MacPherson strut geometry specifically for front-wheel-drive performance applications. Careful attention to steering axis inclination and caster angles minimizes both torque steer and camber changes during hard cornering.

Inverted Monotube Struts: Some high-performance applications flip the strut upside-down, mounting the larger piston end at the top and the shaft at the bottom. This configuration increases the structure’s resistance to bending loads, improving steering precision under high cornering forces. Porsche uses inverted struts in the 911 GT3 and Cayman GT4, while Subaru employs them in the WRX STI.

Chapman Strut: Rear Application Adaptation

Colin Chapman, the legendary Lotus founder, adapted MacPherson’s front suspension concept for rear suspension applications. The Chapman strut works on the same principles but omits the steering capability since rear wheels don’t turn (in most vehicles). Chapman used this design extensively on Lotus sports cars and even in his Formula 1 race cars, demonstrating that cost reduction wasn’t the only motivation—the design worked exceptionally well when properly engineered.

The original Lotus Elan, universally praised as one of the best-handling cars of its era, used Chapman struts at all four corners. This proves that MacPherson-type suspension can deliver world-class handling when matched with appropriate chassis stiffness, component quality, and geometric optimization.

Common Problems and Symptoms

Like all mechanical systems, MacPherson strut suspensions experience wear and eventually require maintenance or component replacement. Recognizing symptoms early prevents safety issues and more expensive repairs down the road.

Worn Strut Dampers

Symptoms You’ll Experience:

- Excessive bouncing after hitting bumps, taking multiple oscillations to settle

- “Floating” sensation at highway speeds, especially over rolling pavement

- Nose diving during braking, more than when the car was new

- Longer stopping distances, as the suspension fails to maintain tire contact

- Visible oil residue on the strut body indicating seal failure

What’s Happening Inside: Over time and miles, the seals that contain the strut’s hydraulic fluid begin to deteriorate. High-frequency motion, temperature cycling, and contamination all contribute to seal wear. Once seals fail, hydraulic fluid leaks out, dramatically reducing damping effectiveness. The shock can no longer control spring oscillations properly, allowing the wheel to bounce excessively.

Pressurized gas can also escape, causing the strut to operate with reduced efficiency even without visible fluid leaks. Internal valve components wear from millions of cycles, changing the damping characteristics until the strut no longer matches its original performance.

DIY Inspection Method: Push down firmly on one corner of the vehicle, then release. The suspension should rebound once and settle without additional bouncing. If it oscillates two or more times, suspect worn dampers. Visual inspection for oil leaks provides additional confirmation, though remember that a light oil film may be normal—look for fresh fluid actively dripping or accumulating dirt.

Professional Perspective: Identifying failing shock absorbers requires systematic inspection, as symptoms often develop gradually and drivers adapt unconsciously to deteriorating performance. Testing equipment that measures damping force provides objective assessment but rarely appears in typical repair shops.

Failed Upper Strut Mount Bearing

Symptoms You’ll Experience:

- Clunking or knocking noises when turning the steering wheel, especially from a stop

- Notchy or uneven steering feel, like the wheel catches at certain angles

- Steering wheel sits off-center when driving straight

- Popping sounds from the front suspension over bumps

What’s Happening: The upper strut mount contains a bearing that allows the strut to rotate during steering inputs. This bearing handles enormous loads—supporting the vehicle’s weight while accommodating thousands of steering cycles and absorbing road impacts. Eventually, the bearing races develop wear patterns, grease breaks down, or rubber isolators deteriorate.

Rust and corrosion accelerate failure in salt-belt regions. The rubber components that isolate vibration can crack and separate, allowing metal-to-metal contact that produces clunking noises. Bearing failure doesn’t just affect ride quality—it can compromise steering precision and even alignment settings.

Common Inspection Finding: Upper mount bearing failure is a frequent MOT or safety inspection advisory in many regions. Inspectors check for play at the top of the strut and listen for noises during steering input while the vehicle is on a lift.

Broken or Sagging Coil Springs

Symptoms You’ll Experience:

- Vehicle sits noticeably lower on one corner compared to others

- Loud knocking or banging sounds over bumps, sounding like metal-on-metal contact

- Uneven tire wear, particularly excessive inner or outer edge wear

- Handling feels unbalanced, pulling to one side

What’s Happening: Coil springs gradually lose height over tens of thousands of miles as the metal fatigues and the spring’s wire diameter very slightly reduces under constant compression. This sag rarely causes immediate problems but changes suspension geometry, potentially affecting alignment and handling.

Complete spring failure—where the coil actually breaks—is less common but more dramatic. Springs can fracture due to corrosion (especially in northern climates with road salt), manufacturing defects, or fatigue from extreme loads. A broken spring allows the suspension to collapse further than designed, potentially causing the coil fragments to interfere with other components or even the tire.

Safety Impact: Failing coil springs affect suspension geometry, which in turn impacts handling stability and tire wear. The changes may be subtle initially but progressively worsen. A completely broken spring represents an immediate safety concern and requires towing rather than driving the vehicle.

Control Arm and Ball Joint Issues

Lower Control Arm Bushing Wear: Rubber or polyurethane bushings that mount the control arm to the chassis deteriorate from age, heat cycles, and chemical exposure. Symptoms include clunking over bumps, vague steering response, and accelerated tire wear. Visual inspection reveals cracked, torn, or oil-contaminated rubber bushings that require replacement.

Ball Joint Degradation: The critical pivot point between control arm and steering knuckle experiences enormous multi-directional forces. Modern sealed ball joints eventually wear out their internal bearings, allowing excessive play. Warning signs include clunking noises over bumps, steering wander, and visible rubber boot damage that allows contamination into the joint.

These components connect directly to critical steering and suspension functions, making them safety-sensitive items that require prompt attention. For detailed guidance on identifying issues, review our articles on control arm bushing problems and ball joint failure symptoms.

Expected Service Life and Wear Patterns

Understanding typical component longevity helps with maintenance planning:

Strut Dampers: 50,000-100,000 miles (80,000-160,000 km) under normal conditions. Rough roads, aggressive driving, and vehicle overloading accelerate wear. Many manufacturers recommend inspection at 50,000 miles.

Upper Strut Mounts: Often outlast the original struts, reaching 100,000-150,000 miles. However, severe potholes or hard impacts can cause premature failure. Replacement during strut service prevents future labor duplication.

Coil Springs: Typically last 150,000+ miles in normal conditions. Salt belt vehicles may experience corrosion-related failures earlier. Springs gradually sag over time, with height loss of 20-30mm possible over the vehicle’s life.

Ball Joints and Control Arm Bushings: Service intervals vary widely by vehicle and driving conditions, ranging from 60,000 to 150,000+ miles. Annual inspection catches problems early.

Replacement and Repair Considerations

When MacPherson strut components require service, understanding your options—and limitations—helps make informed decisions about DIY repairs versus professional service.

Skill Level Assessment and DIY Capabilities

Beginner DIY Tasks:

- Visual inspections for obvious damage, leaks, or wear

- Identifying symptoms that require professional diagnosis

- Understanding when to seek expert help

Intermediate DIY Projects:

- Complete strut assembly replacement using pre-loaded (quick strut) units

- Control arm replacement on straightforward designs

- Upper mount replacement with proper tools

Advanced DIY Tasks:

- Individual component replacement requiring spring compression

- Complex control arm configurations with multiple bushings

- Troubleshooting subtle handling issues

Always Professional:

- Wheel alignment after any suspension work

- Ball joint replacement on certain vehicles with press-fit designs

- Diagnosis requiring specialized suspension measurement equipment

The Spring Compression Safety Warning

CRITICAL SAFETY NOTICE: Coil springs under compression store enormous energy—often 500+ pounds of force. Improper spring compression or sudden release can cause springs to violently launch from the strut assembly, resulting in severe injury or death.

If you choose to service individual strut components rather than using pre-loaded assemblies, you absolutely must use proper coil spring compressors designed for automotive use. Chains, ratchet straps, rope, or other improvised methods are completely inadequate and extremely dangerous. Even with proper spring compressors, work carefully and ensure the spring is securely captured before removing the upper strut mount nut.

Many experienced DIY mechanics choose pre-loaded strut assemblies specifically to avoid spring compression risks, accepting the slightly higher cost as worthwhile insurance. There’s no shame in this decision—professional technicians use similar assemblies to improve efficiency and safety.

Cost Breakdown and Service Options

Pricing varies significantly based on vehicle make, parts quality, and labor rates in your area. These 2024 estimates provide general guidance:

Component Costs (Aftermarket Quality Parts):

- Complete loaded strut assembly: $150-$350 per strut

- Individual strut cartridge (no spring/mount): $50-$150 per strut

- Upper strut mount bearing: $20-$60 per side

- Coil spring: $40-$100 per side

- Lower control arm: $60-$150 per side

- Ball joint: $30-$80 per joint

Labor Costs (Professional Service):

- Front strut pair replacement: $200-$400

- Upper mount replacement (during strut service): $50-$100 additional

- Control arm replacement: $100-$200 per side

- Ball joint replacement: $100-$250 per side

- Wheel alignment (four-wheel): $75-$150

Typical Total Project Costs:

- Both front struts (loaded assemblies) + alignment: $500-$1,100 professionally

- DIY strut replacement (doing your own labor): $300-$700 for parts plus alignment

OEM (Original Equipment Manufacturer) parts typically cost 30-50% more than quality aftermarket alternatives. For most applications, reputable aftermarket brands like Monroe, KYB, Bilstein, or Gabriel provide excellent performance and durability at lower cost than dealer parts.

Required Tools and Equipment

Basic DIY Strut Replacement:

- Quality socket set (metric, typically 14mm-24mm sizes)

- Breaker bar for stubborn fasteners

- Torque wrench (essential for proper reassembly)

- Floor jack rated for your vehicle’s weight

- Jack stands (never work under a vehicle supported only by a jack)

- Penetrating oil for rusty fasteners

- Basic hand tools (wrenches, pliers, pry bars)

Spring Compression (If Servicing Individual Components):

- Professional-grade coil spring compressors (NOT the screw-type hardware store versions)

- Safety glasses and gloves

- Work space that allows safe spring compression away from people

Specialized Tools That Might Be Needed:

- Ball joint separator or pickle fork

- Control arm bushing tools (if replacing bushings separately)

- Specific tools for your vehicle (some manufacturers require special sockets or adapters)

Professional Equipment Required:

- Computerized wheel alignment system

- Specialized diagnostic equipment for suspension geometry measurement

- Professional-grade spring compressors and safety fixtures

Complete Strut Assembly vs. Component Replacement

You’ll face a fundamental decision when struts need replacement: buy complete loaded assemblies or replace individual components?

Complete Loaded Assemblies (Quick Struts) – Advantages:

- No spring compression required

- Faster installation (typically 2-3 hours for both fronts)

- Guaranteed component compatibility

- New springs and mounts eliminate future failures

- Safer for DIY installation

Complete Loaded Assemblies – Disadvantages:

- Higher upfront cost ($100-$150 more per corner than strut-only)

- Less flexibility for performance customization

- May replace springs that weren’t yet worn

Individual Component Replacement – Advantages:

- Lower parts cost if springs and mounts are still good

- Allows spring rate customization for performance

- More economical if only strut dampers have failed

Individual Component Replacement – Disadvantages:

- Requires safe spring compression capability

- Time-consuming disassembly and reassembly

- Risk of damaging existing components during service

- Labor cost often negates parts savings at professional shops

Most professional shops now prefer loaded assemblies because labor savings offset the higher parts cost while improving safety and reducing comebacks. For DIY mechanics without spring compression experience, loaded assemblies represent the clear choice.

After Replacement: The Alignment Imperative

Any time you disconnect suspension components—struts, control arms, tie rods, or ball joints—wheel alignment must be verified and adjusted. Even if you carefully mark positions before disassembly, suspension geometry changes after component replacement due to:

- Different component dimensions (even “identical” parts vary slightly)

- Bushing compression and settling under vehicle weight

- Torque-dependent alignment changes as fasteners reach specification

Driving on improper alignment accelerates tire wear, compromises handling safety, and prevents you from realizing the benefits of your new suspension components. The alignment cost isn’t optional—it’s an essential part of proper suspension service.

Professional alignment shops use computerized systems that measure camber, caster, toe, and other angles, comparing them to manufacturer specifications. Most vehicles allow adjustment of toe and some degree of camber at the front; rear alignment capabilities vary by design. The technician makes adjustments to bring all angles within specification, ensuring the vehicle tracks straight, handles predictably, and wears tires evenly.

Conclusion: Understanding Your Vehicle’s MacPherson Strut Suspension

After 80 years in production, the MacPherson strut remains the world’s most popular suspension design—and for good reasons. This elegant system balances cost, performance, packaging efficiency, and reliability in ways that few alternatives can match. From economy commuters to sports car icons, MacPherson struts deliver dependable performance across an enormous range of applications.

The key insights we’ve covered:

Design Fundamentals: MacPherson struts combine shock absorbing, spring support, and steering pivot functions into a compact, cost-effective package that revolutionized automotive suspension design.

Operational Excellence: Through careful integration of coil springs, hydraulic damping, and precision bearings, these systems maintain tire contact with the road while isolating passengers from road irregularities.

Engineering Tradeoffs: The system’s primary limitation—less tuning flexibility than multi-link or double wishbone designs—rarely matters for street driving but can affect extreme performance applications.

Component Longevity: Expect 50,000-100,000 miles from strut dampers, with springs and other components often lasting considerably longer under normal conditions.

Maintenance Requirements: Regular visual inspections, prompt attention to symptoms, and appropriate replacement intervals keep MacPherson strut suspensions operating safely and effectively.

When to Consult a Professional

While knowledgeable DIY enthusiasts can handle many MacPherson strut service tasks, certain situations demand professional expertise:

Complex Diagnostics: Subtle handling problems, unusual noises, or vehicle behavior that doesn’t match common symptom patterns often requires specialized diagnostic equipment and experienced interpretation.

Spring Compression Operations: Without proper training and equipment, spring compression presents serious safety risks. Professional technicians have both the tools and experience to perform this work safely.

Wheel Alignment: Post-service alignment verification and adjustment requires computerized equipment that measures suspension geometry to within 0.1-degree precision. This isn’t a DIY task—plan to visit an alignment shop after any suspension component replacement.

Safety-Critical Components: Ball joints, control arms, and steering knuckles directly affect vehicle control. If you’re uncertain about proper installation procedures, torque specifications, or quality assessment, professional service provides peace of mind.

Advanced Diagnostics: Determining whether handling characteristics result from worn suspension components, improper alignment, tire issues, or driver technique often requires professional test driving experience and systematic elimination of variables.

Maintenance Best Practices for Long Suspension Life

Proactive care extends MacPherson strut component service life:

Regular Visual Inspections: During oil changes or tire rotations, visually inspect struts for oil leaks, damaged boots, rust, or physical damage. Check control arm bushings for cracking or deterioration. Look for uneven tire wear patterns indicating alignment or suspension problems.

Prompt Symptom Response: Unusual noises, handling changes, or ride quality deterioration warrant investigation. Problems rarely improve on their own and often cascade into additional component failures if ignored.

Replace in Pairs: Always replace struts, springs, or control arms in pairs across an axle. Mismatched components create imbalanced handling and can affect vehicle stability.

Quality Matters: While budget parts seem attractive, quality suspension components from reputable manufacturers provide better performance, longer service life, and more predictable behavior. The modest cost difference pays dividends in reliability.

Professional Alignment Verification: After any suspension service, wheel alignment verification ensures components operate within design parameters. The modest cost prevents expensive tire replacement and ensures safe handling.

Drive Considerately: While MacPherson struts handle normal driving demands well, aggressive pothole impacts, consistent overloading, and extreme off-road use all accelerate component wear. Avoiding obvious road hazards when possible extends service life.

The MacPherson strut suspension system represents one of automotive engineering’s most successful designs—a testament to the elegance of Earle MacPherson’s original vision. Understanding how these systems work, recognizing when they need attention, and providing appropriate maintenance ensures your vehicle continues delivering the safe, comfortable, and responsive driving characteristics MacPherson struts are known for providing.

For a comprehensive overview of how steering and suspension systems work together to control your vehicle, explore our complete guide to steering and suspension systems.