Every time you turn your steering wheel while driving over uneven pavement, a remarkable mechanical component makes it possible: the ball joint. These precision-engineered pivot points are working constantly beneath your vehicle, enabling your wheels to move up and down with the suspension while simultaneously turning left and right for steering. Without properly functioning ball joints, your vehicle would be unable to maintain the smooth, controlled handling you experience daily.

Ball joints are spherical bearings that connect your vehicle’s control arms to the steering knuckles. Their ball-and-socket design—similar to your hip joint—allows three-dimensional articulation that no other single component can provide. This unique capability makes them indispensable in virtually all modern vehicle suspensions, whether front-wheel drive sedans, rear-wheel drive sports cars, or heavy-duty pickup trucks.

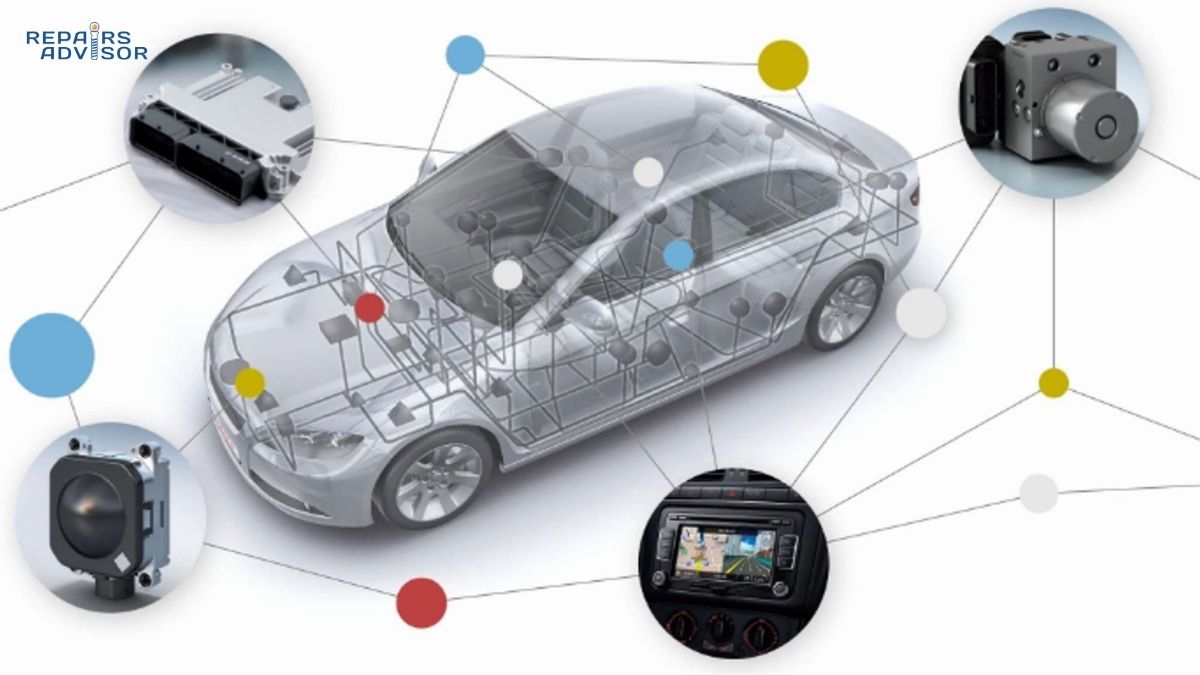

You’ll find ball joints in the front suspension of nearly every vehicle on the road today. MacPherson strut systems use one ball joint per front wheel, while double wishbone and short-long arm suspensions employ both upper and lower ball joints on each side. Understanding how your car’s suspension works provides helpful context for appreciating the critical role ball joints play in this complex system.

Because ball joints are safety-critical components, their failure can result in loss of vehicle control. A severely worn ball joint can allow the ball stud to separate from its housing, potentially causing a wheel to detach from the suspension. This article will help you understand how ball joints function, the different types used in various suspension designs, how to recognize wear symptoms, and when professional service becomes necessary.

What Are Ball Joints?

Basic Design and Construction

A ball joint is essentially a highly engineered ball-and-socket assembly designed to withstand enormous forces while allowing smooth movement in multiple directions. The main component is the ball stud—a precision-machined shaft featuring a polished spherical ball on one end and a tapered, threaded section on the other. The ball portion is manufactured from hardened steel and polished to an extremely smooth finish, typically achieving surface roughness measurements in microinches. This mirror-like polish is critical for minimizing friction and preventing premature wear.

The bearing socket surrounds and contains the ball, providing the surface against which it rotates. In modern sealed ball joints, this bearing is typically made from injection-molded polymers like polyurethane or reinforced nylon. These materials offer excellent wear resistance, natural lubricity, and quiet operation without requiring maintenance. Performance-oriented aftermarket ball joints often use metal-on-metal bearing surfaces with grease retention systems, sacrificing some quietness for increased load capacity and serviceability.

Protecting these precision internal components is the dust boot—a flexible rubber or polyurethane shield that seals the opening where the ball stud exits the housing. This boot prevents road debris, water, and corrosive salt from contaminating the bearing surfaces while retaining lubricant inside the joint. The dust boot is often the first component to fail, and once compromised, rapid deterioration of the internal components typically follows.

The housing itself is a heavy-duty metal casing that contains all internal parts and provides the mounting interface to the control arm. Inside, a backing plate or spring washer (often called a Belleville washer) maintains constant preload on the bearing assembly, automatically compensating for initial wear and keeping the joint tight. Some ball joints include a grease fitting (Zerk fitting) that allows periodic lubrication, while modern sealed designs contain lifetime lubricant and cannot be serviced.

The connection between ball joints and control arms is fundamental to suspension geometry, as these components work together to maintain proper wheel positioning through all ranges of motion.

Location in Vehicle

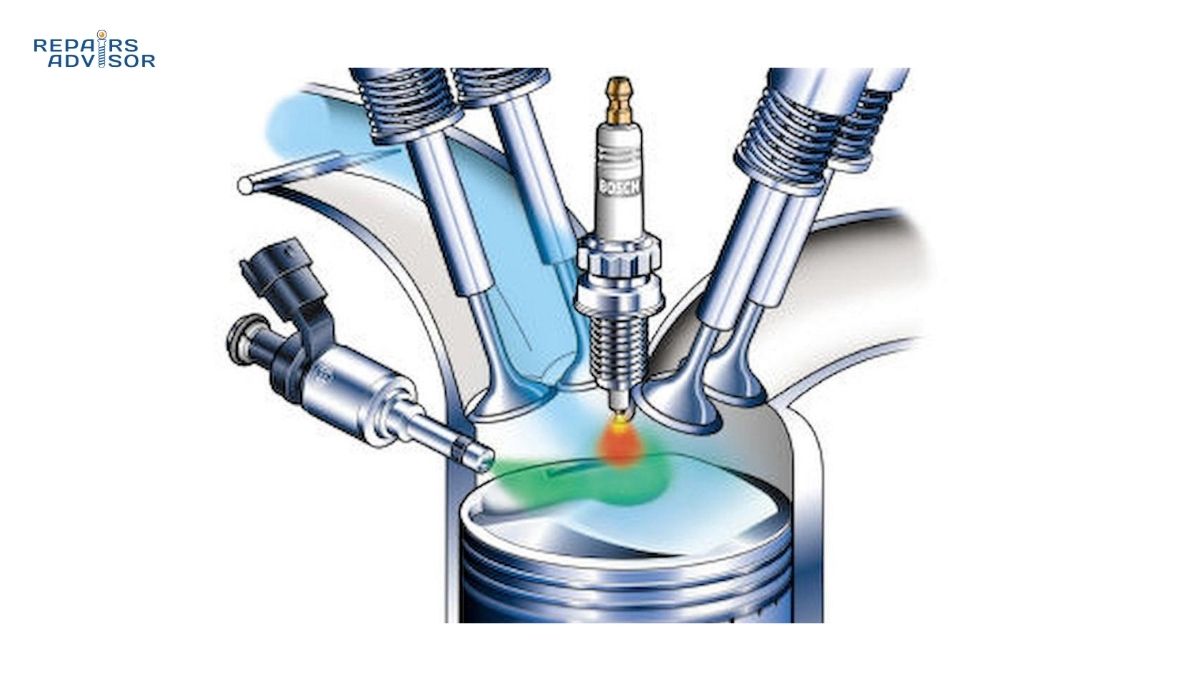

Ball joints are strategically positioned at the crucial junction between the control arms and steering knuckle, creating the pivot points that enable both suspension travel and steering movement. Their exact location and quantity depends on your vehicle’s suspension design.

In MacPherson strut suspension systems—the most common design in modern front-wheel-drive vehicles—you’ll find a single lower ball joint on each side, for a total of two ball joints in the front suspension. The strut itself connects directly to the top of the steering knuckle, eliminating the need for an upper ball joint. This design is compact, cost-effective, and provides excellent packaging efficiency in tight engine compartments.

Double wishbone and short-long arm (SLA) suspension systems employ both upper and lower ball joints on each front wheel, totaling four ball joints in the front suspension. The upper ball joint connects the upper control arm to the top of the steering knuckle, while the lower ball joint links the lower control arm to the bottom of the knuckle. This configuration allows for superior suspension geometry control and is commonly found on rear-wheel-drive vehicles, performance cars, and trucks.

Some sophisticated multi-link suspension designs also incorporate ball joints in rear suspension applications. These rear ball joints typically serve as pivot points in the complex linkage arrangements that control wheel movement, camber, and toe angles during suspension compression and extension.

Solid front axle configurations, still used in some heavy-duty four-wheel-drive trucks, feature upper and lower ball joints that work differently than independent suspension designs. In these applications, both joints share the vehicle’s weight relatively equally and experience similar loading patterns.

How Ball Joints Function

Three-Axis Articulation

The remarkable capability of ball joints lies in their ability to allow rotation in multiple planes simultaneously while maintaining structural integrity under tremendous loads. This three-dimensional movement is what separates ball joints from simpler pivot designs like bushings or hinges.

In the vertical plane, ball joints accommodate suspension compression and extension as your vehicle travels over bumps, dips, and uneven surfaces. Depending on your vehicle’s suspension design, this vertical travel typically ranges from one to four inches. As the suspension compresses when hitting a bump, the ball rotates within its socket to allow the control arm angle to change while keeping the steering knuckle properly oriented. During extension—such as when a wheel drops into a pothole—the joint articulates in the opposite direction, again allowing the necessary geometric changes.

Lateral movement for steering represents another crucial axis of articulation. When you turn the steering wheel, the steering rack and pinion system pushes or pulls the steering knuckle left or right. The ball joints must allow this steering rotation—typically 30 to 40 degrees in each direction—while maintaining their load-carrying and suspension functions. This simultaneous multi-axis movement would be impossible with conventional hinges or bushings.

Additionally, ball joints accommodate limited rotational movement to handle changes in suspension geometry during travel. As the suspension moves through its range, the relative angles between control arms and steering knuckle constantly change. The ball joint’s spherical design allows these geometric variations without binding or creating stress.

The ultra-low friction achieved by the polished ball rotating against the precision bearing surface enables all this movement to occur smoothly with minimal resistance. This low friction is essential for responsive steering feel and proper suspension function. The design parallels how MacPherson strut suspension systems integrate these pivot points into the overall suspension geometry.

Load-Bearing vs. Follower Types

Not all ball joints perform identical functions within the suspension system. Understanding the critical distinction between load-bearing and follower ball joints helps explain why some joints wear faster than others and why replacement intervals can vary significantly.

Load-Bearing Ball Joints:

Load-bearing ball joints support a substantial portion of your vehicle’s weight—typically between 500 and 1,500 pounds or more per joint, depending on vehicle size and weight distribution. These joints experience constant stress from vehicle weight in addition to the dynamic forces generated during driving, braking, and cornering.

Load-bearing joints are further classified into compression-loaded and tension-loaded designs based on how forces are applied. In compression-loaded configurations, the coil spring is mounted on the lower control arm, causing suspension forces to push the ball stud deeper into its socket. This design is most common and offers the advantage that even severe wear is less likely to result in catastrophic separation since gravity and spring force continue pressing the ball into the housing.

Tension-loaded ball joints occur when the spring is mounted on the upper control arm. In this configuration, suspension forces attempt to pull the ball stud out of its socket. While proper design prevents this under normal conditions, tension-loaded joints can be more prone to catastrophic failure if wear becomes extreme, as the forces actively work to separate the stud from the housing.

Load-bearing joints typically wear faster than follower types due to the additional stress from constantly supporting vehicle weight. The combination of rotational movement and high static loads accelerates bearing surface wear. Double wishbone suspension systems must carefully engineer which ball joints carry loads based on spring mounting location.

Follower Ball Joints:

Follower ball joints provide the necessary pivot function without supporting vehicle weight. In MacPherson strut systems, the lower ball joint is a follower design because the strut’s top mount bearing carries the vehicle’s weight. These joints still handle significant lateral forces during cornering and longitudinal forces during braking, but they’re not compressed or tensioned by static vehicle weight.

Upper ball joints in many double-wishbone systems also function as followers when the coil spring is mounted on the lower control arm. These joints maintain precise alignment and allow steering movement but transfer weight-bearing duties to the lower joints.

Follower ball joints incorporate preloaded designs using spring washers or Belleville springs that automatically compensate for wear over the joint’s service life. This preload system maintains tight tolerances and prevents looseness from developing as the bearing surfaces wear gradually. Because they don’t carry vehicle weight constantly, follower joints typically achieve longer service life than their load-bearing counterparts—often 1.5 to 2 times longer under similar driving conditions.

Interaction with Suspension Geometry

Ball joints are fundamental to maintaining proper suspension geometry throughout the full range of suspension travel. As your vehicle’s suspension compresses and extends, the relative positions of all suspension components change constantly. Ball joints enable these movements while helping preserve critical alignment angles.

The three primary alignment angles—camber, caster, and toe—must remain within specification despite suspension movement to ensure proper tire contact with the road surface. Ball joints allow the steering knuckle to maintain its relationship with the control arms as geometric angles change during suspension articulation. Understanding steering geometry fundamentals helps clarify why ball joint precision is so critical.

When ball joints begin to wear and develop excessive play, alignment accuracy suffers dramatically. A worn ball joint allows the steering knuckle to shift positions it shouldn’t reach, directly affecting camber and toe angles. This misalignment reduces the tire’s contact patch with the road surface, particularly dangerous during cornering when maximum grip is needed.

During cornering, ball joints experience their highest stress levels as lateral forces try to push the wheels outward. Properly functioning ball joints resist these forces while still allowing the suspension to compress on the outside wheels and extend on the inside wheels—movements necessary for maintaining optimal tire contact during turns.

Ball Joint Components in Detail

Internal Components

Ball Stud Design:

The ball stud represents the most critical precision component within the ball joint assembly. Manufacturers machine these studs from high-carbon or alloy steel, then heat-treat them to achieve the perfect balance of hardness and toughness. The spherical ball portion undergoes precision grinding and polishing to achieve surface finishes measured in microinches—essentially creating a mirror-smooth surface that minimizes friction and prevents accelerated wear.

The tapered threaded shaft extends from the ball and provides the connection point to the steering knuckle. This taper, typically ranging from 7 to 12 degrees depending on application, creates a wedging action when the retaining nut is tightened. The taper ensures a solid, vibration-resistant connection that can withstand the extreme forces encountered during driving. The threads must be precision-cut to prevent the nut from loosening under vibration and impact.

Surface finish quality on the ball directly determines the joint’s friction characteristics and wear rate. Any microscopic imperfections in this surface create stress concentration points that accelerate bearing wear. Premium ball joints undergo additional finishing processes including superfinishing or lapping to achieve the smoothest possible surface.

Bearing Materials:

Original equipment sealed ball joints predominantly use injection-molded polymer bearings, typically manufactured from high-performance materials like glass-filled nylon or polyurethane compounds. These engineered plastics offer several advantages: they’re naturally self-lubricating, they dampen vibration and noise effectively, and they resist corrosion. Modern polymer formulations can withstand the pressures and temperatures encountered in ball joint applications while providing years of maintenance-free service.

Aftermarket performance ball joints often employ metal-on-metal bearing surfaces—typically bronze or specially treated steel—combined with grease retention systems. Metal bearings can support higher loads and offer the advantage of serviceability through grease fittings. The trade-off is increased noise transmission and the requirement for regular maintenance. However, for heavy-duty applications or vehicles subject to harsh conditions, metal bearings’ superior load capacity and repairability often justify these compromises.

Some advanced designs combine materials, using metal cages to support polymer bearing elements or incorporating multiple bearing surfaces to distribute loads more effectively. These hybrid approaches attempt to capture the benefits of both material types while minimizing their respective drawbacks.

Protective Boot:

The protective dust boot serves as the ball joint’s first line of defense against the elements. This flexible component must seal effectively while accommodating the joint’s full range of motion—a challenging engineering problem. Manufacturers typically use either natural rubber or synthetic materials like polyurethane, each offering distinct characteristics.

Rubber boots provide excellent flexibility and sealing properties but can deteriorate when exposed to petroleum products, ozone, and temperature extremes. Polyurethane boots offer superior resistance to oil, grease, and temperature variations but may become stiff in extreme cold. The boot attaches to both the housing and the ball stud using circlips, clamps, or molded retention features.

Boot failure is often the beginning of the end for a ball joint. Once torn or displaced, the boot allows water, dirt, and road salt to enter the bearing cavity while allowing lubricant to escape. Contamination rapidly accelerates wear, and a ball joint with a compromised boot typically fails within months rather than years. This is why visual boot inspection during routine service is so important—catching boot damage early allows replacement before internal contamination occurs.

The relationship between ball joints and control arm bushings in protecting suspension components from contamination and wear highlights the importance of these protective elements.

Lubrication Systems

Sealed Ball Joints (Modern OEM):

Most modern original equipment ball joints use sealed designs that contain lubrication installed during manufacturing. Rather than traditional grease, many employ solid lubricant inserts—typically specialized plastic compounds with embedded lubricating particles. As the ball stud moves, it wears microscopic amounts of this material, continuously releasing lubricant to the bearing surface.

This maintenance-free approach eliminates the need for periodic greasing and ensures consistent lubrication throughout the joint’s service life. The sealed design also prevents contamination more effectively than serviceable joints since there’s no grease fitting opening where dirt could potentially enter. However, once these joints wear out, they cannot be rejuvenated—replacement is the only option.

Sealed ball joints typically achieve service lives between 70,000 and 150,000 miles under normal driving conditions. Variables including road quality, climate, vehicle weight, and driving style significantly affect longevity. Vehicles operated in harsh winter climates with road salt exposure often experience shorter ball joint life due to corrosion attacking the boot and housing despite the sealed design.

Greaseable Ball Joints (Serviceable):

Traditional greaseable ball joints feature a Zerk fitting—a one-way valve that allows grease injection while preventing contamination from entering. These serviceable designs enable periodic maintenance that can significantly extend service life if performed correctly and consistently.

Proper maintenance intervals for greaseable ball joints vary based on design and application, but generally range from every 2,000 to 5,000 miles. Performance applications with low-friction metal bearings may require more frequent service, while heavy-duty designs with robust seals might tolerate longer intervals. The greasing process serves dual purposes: it provides fresh lubricant while using pressure to purge old grease and any contaminants that may have entered the joint.

When properly maintained, greaseable ball joints can achieve service lives exceeding 100,000 to 200,000 miles—substantially longer than sealed designs. However, this advantage depends entirely on consistent maintenance. Neglected greaseable joints often fail sooner than sealed joints because dried-out lubricant creates higher friction and accelerated wear. Understanding proper ball joint inspection and maintenance helps ensure these serviceable designs reach their full lifespan potential.

Types of Ball Joints by Suspension Design

MacPherson Strut Applications

MacPherson strut suspension systems represent the most common front suspension design in modern vehicles, particularly front-wheel-drive applications. This design uses a single lower ball joint per side—just two ball joints total in the front suspension—making it simpler and less expensive than designs requiring four joints.

In this configuration, the lower ball joint functions as a follower type because the strut’s upper mount bearing carries the vehicle’s weight. The ball joint still experiences significant stress from lateral cornering forces and longitudinal braking forces, but it doesn’t support static vehicle weight. This reduced loading generally translates to longer service life compared to load-bearing joints in other suspension types.

The lower stress environment and follower design mean MacPherson strut ball joints often remain serviceable for 100,000 miles or more under normal conditions. Additionally, replacement is typically more accessible than in double-wishbone systems since there’s only one joint per side to service. However, this advantage varies significantly by vehicle—some manufacturers design extremely tight engine bays where even single ball joint replacement requires substantial disassembly.

The strut connects directly to the steering knuckle’s upper section, eliminating the upper control arm and upper ball joint entirely. This packaging efficiency is why MacPherson struts dominate front-wheel-drive applications where engine compartment space is at a premium. Understanding how shock absorbers and struts work together with ball joints provides insight into this integrated suspension design.

Short-Long Arm (SLA) / Double Wishbone

Short-long arm and double wishbone suspension designs employ both upper and lower ball joints on each front wheel, requiring four ball joints total in the front suspension. This configuration allows superior control over suspension geometry and is favored for performance applications and rear-wheel-drive vehicles where packaging constraints are less severe.

The critical factor determining which joints are load-bearing versus follower is the coil spring mounting location. In the most common configuration, the spring sits on the lower control arm, making the lower ball joints load-bearing (compression-loaded) while the upper joints function as followers. Less commonly, the spring mounts on the upper control arm, reversing the load-bearing responsibilities—upper joints become load-bearing (tension-loaded) while lower joints become followers.

Load-bearing joints in SLA systems typically wear faster than their follower counterparts due to the additional stress from supporting vehicle weight. Best practice dictates replacing both upper and lower ball joints simultaneously on both sides when wear is detected, even if only one joint shows symptoms. This approach ensures balanced suspension performance and prevents premature failure of the remaining old joints due to altered suspension dynamics.

Replacement complexity in SLA systems often exceeds MacPherson strut designs because accessing four ball joints requires more extensive disassembly. Additionally, proper replacement often necessitates special tools including ball joint presses or hydraulic separators to remove pressed-in joints from control arms. The precision required and safety-critical nature make professional service strongly advisable.

Multi-Link and Rear Suspensions

Some sophisticated suspension designs incorporate ball joints in rear suspension applications, though this is less common than front suspension use. Multi-link rear suspension systems may employ ball joints as articulation points in their complex linkage arrangements, allowing the precise control over wheel movement, camber, and toe angles that these designs offer.

Rear suspension ball joints are generally follower types since vehicle weight is typically supported by separate bushing systems rather than the ball joints themselves. These joints primarily provide the articulation needed for complex geometric changes during suspension travel and allow small amounts of compliance that improve ride quality and handling.

Independent rear suspensions on performance vehicles and luxury cars often use ball joints to connect lateral links, toe links, or camber links to the wheel hub carrier. These joints must accommodate the same multi-axis movement as front ball joints but typically experience lower steering-related loads since rear wheels don’t turn as dramatically as front wheels.

In contrast, rear torsion-beam suspension designs—common in economy cars—typically don’t use ball joints at all, relying instead on bushing-based pivot points. This simpler approach reduces cost and complexity while still providing acceptable performance for less demanding applications.

Solid Front Axle (4×4 Trucks)

Solid front axle configurations, still used in some heavy-duty four-wheel-drive trucks and off-road vehicles, employ ball joints differently than independent suspension designs. In these applications, the upper and lower ball joints on each side share the vehicle’s weight relatively equally since there’s no separate spring mounting location creating load differentiation.

Both upper and lower ball joints in solid axle applications experience similar wear rates because loads are distributed more evenly. This contrasts sharply with independent suspensions where load-bearing joints wear substantially faster than followers. Consequently, manufacturers and technicians generally recommend replacing all four ball joints simultaneously when service is required on solid front axles.

An additional practical consideration in solid axle service is that removing upper ball joints is typically necessary to access lower ball joints. This access requirement makes replacing both joints simultaneously more cost-effective from a labor perspective since the disassembly work is already being performed. Leaving old upper joints in place while replacing lowers would require repeating the entire labor-intensive disassembly process when the uppers eventually fail.

Solid axle ball joints also tend to be more robust than independent suspension designs because they must handle the additional stresses of front axle articulation during off-road use. These heavy-duty joints often feature larger ball studs, more substantial housings, and enhanced sealing systems to withstand extreme conditions.

Wear Patterns and Failure Modes

Normal Wear Progression

Ball joint wear is an inevitable consequence of constant movement under load. Even with perfect lubrication and no contamination, the bearing surfaces gradually wear through millions of articulation cycles. As the polished ball rotates against the bearing material, microscopic amounts of material transfer or abrade away with each movement.

Initially, the Belleville washer or preload spring compensates for this wear by maintaining constant pressure on the bearing assembly. This self-adjusting mechanism keeps the joint tight and prevents detectable looseness during the early stages of wear. However, as material continues wearing away, the clearance between ball and socket gradually increases beyond the preload system’s compensation range.

Manufacturers specify maximum allowable play for their ball joints, typically ranging from 0.020 to 0.060 inches depending on design and application. This specification represents the point where clearance becomes large enough to affect suspension geometry and vehicle handling. Once play exceeds specification, the joint cannot maintain proper wheel positioning, and replacement becomes necessary.

The rate of wear progression depends on numerous factors including joint design, lubrication quality, contamination level, vehicle weight, driving style, and road conditions. A well-maintained greaseable ball joint on a light vehicle driven on smooth roads might accumulate 150,000 miles before reaching wear limits, while a sealed joint on a heavy vehicle subjected to harsh conditions might fail at 70,000 miles.

Compression-Loaded Joint Failure

Compression-loaded ball joints—where spring forces push the ball stud into the socket—exhibit a characteristic wear pattern as they deteriorate. The constant compression causes the ball to grind progressively deeper into the bearing material, creating a progressively larger cavity in the socket. This erosion increases the clearance between ball and socket, producing looseness and excessive play.

As wear progresses, you’ll notice symptoms progressing from occasional clicking noises over bumps to constant clunking sounds during any suspension movement. The looseness allows the ball to shift position within the worn socket, creating the audible impacts as it moves from one side of the clearance to the other.

The failure mode of compression-loaded joints is generally gradual deterioration rather than catastrophic separation. Because vehicle weight and spring force continuously push the ball stud into the housing, the joint typically remains partially functional even when severely worn. However, “less catastrophic” doesn’t mean “safe”—a severely worn compression-loaded joint can still fail completely if subjected to extreme lateral forces during hard cornering or if the housing itself cracks due to stress.

The gradual nature of compression-loaded joint failure provides a window for detection and replacement before catastrophic failure occurs, but only if symptoms are heeded promptly. Ignoring the warning signs of clunking, vibration, or handling changes allows wear to progress to dangerous levels.

Tension-Loaded Joint Failure

Tension-loaded ball joints present a more concerning failure scenario because forces actively attempt to pull the ball stud out of its socket rather than pressing it inward. As the bearing material wears, the ball stud begins pulling against the outer portion of the socket, causing erosion of the retention capability.

The wear pattern in tension-loaded joints focuses stress on the socket’s retention features—typically a backing plate, spring washer, and socket edge that capture the ball and prevent it from pulling out. As these components wear and deform, the retention strength diminishes. Unlike compression-loaded joints where gravity helps keep components together, tension-loaded designs fight against separating forces.

This load direction creates the potential for more catastrophic failure modes. If wear becomes severe enough, the ball stud can pull completely through the worn retention features, causing immediate and complete separation of the steering knuckle from the control arm. This represents a worst-case scenario where the wheel becomes partially disconnected from the vehicle, resulting in immediate loss of control.

Tension-loaded ball joints therefore require even more vigilant monitoring than compression-loaded designs. Any symptoms of wear should prompt immediate professional inspection rather than deferral. The good news is that tension-loaded configurations are less common than compression-loaded designs in modern vehicles, and when used, they’re typically engineered with robust retention features to minimize failure risk.

Common Wear Indicators

Built-in Wear Indicators (Older Applications):

Some ball joints, particularly those manufactured for vehicles from the 1970s through the 1990s, incorporated built-in wear indicators that provided visual confirmation of joint condition. The most common type used the grease fitting itself as an indicator. As the joint wore and the ball settled deeper into the socket, the grease fitting would sink until it became flush with or receded below the housing surface. When flush or recessed, replacement was indicated.

Another indicator design employed a pin or projection extending through a hole in the housing bottom. When the joint was within specification, this pin remained visible protruding from the hole. As wear progressed, the pin would sink until it became flush with the housing or disappeared into the hole, signaling the need for replacement.

These built-in wear indicators are uncommon on modern vehicles because contemporary ball joint designs often load the joints in directions incompatible with these indicator mechanisms. Additionally, modern sealed joints without grease fittings cannot use the grease-fitting-as-indicator approach. This means current vehicles require alternative inspection methods.

Measurement Methods:

Professional ball joint inspection relies on precision measurement tools, particularly dial indicators that can measure play in thousandths of an inch. The technician positions the dial indicator against the steering knuckle or control arm and applies force to load the joint, then measures movement. Comparing the measured play against manufacturer specifications determines whether replacement is necessary.

Visual inspection provides valuable preliminary assessment even without precision tools. Technicians look for torn or damaged dust boots, grease leakage indicating seal failure, rust or corrosion on exposed components, and any visible deformation or damage to the housing. A compromised boot often signals impending failure even if the joint still feels tight, because contamination will rapidly accelerate wear.

Physical testing involves supporting the vehicle properly to unload (for follower joints) or load (for load-bearing joints) the ball joint, then grasping the tire and attempting to rock it in various directions while feeling and listening for play. This method requires experience to interpret correctly because control arm bushings can create similar symptoms, and improper vehicle support can mask ball joint problems.

Symptoms of Worn Ball Joints

Audible Symptoms

The sounds produced by worn ball joints represent one of the earliest and most noticeable warning signs that professional inspection is needed. These noises typically start subtly and progress in both frequency and intensity as wear worsens.

Clunking or knocking sounds during suspension movement—particularly over bumps, expansion joints, or rough pavement—often indicate excessive clearance in the ball joint. The sound occurs as the ball stud shifts position within the worn socket, impacting the bearing surfaces. Initially, you might hear occasional clunks only over significant bumps. As wear progresses, the frequency increases until you hear clunking over even minor road irregularities.

Squeaking or creaking noises when turning the steering wheel, especially when stationary or moving slowly, suggest inadequate lubrication or dried-out bearing surfaces. This symptom is particularly common in greaseable ball joints that haven’t received proper maintenance. The dry metal-on-metal or metal-on-plastic contact creates audible friction as the joint articulates through its range during steering movements.

Rattling sounds during acceleration or braking indicate advanced wear where excessive play allows components to vibrate against each other. The forces generated during acceleration and braking cause the loose joint to shake, creating a distinctive rattling that differs from the clunking heard over bumps.

As deterioration progresses, these sounds intensify and occur more frequently. What begins as occasional clicks over potholes can evolve into constant noise during any driving. This progression pattern makes early symptom recognition crucial—addressing ball joint wear when noises first appear prevents the advanced deterioration that creates dangerous handling conditions.

Handling Symptoms

Worn ball joints significantly affect vehicle handling and steering response because they allow excessive movement in the suspension geometry. These handling changes often develop gradually, making them easier to miss than sudden mechanical failures, but they represent serious safety concerns.

Steering wander is one of the most dangerous symptoms. The vehicle drifts or pulls to one side despite holding the steering wheel straight. When attempting to correct this drift, the vehicle may respond by pulling in the opposite direction, creating a frustrating oscillating pattern. This occurs because excessive ball joint play allows the wheel alignment to shift unpredictably as forces change during driving.

A loose or vague steering feel indicates the steering wheel can move through a small range without producing corresponding wheel movement. This “dead spot” results from clearance in worn ball joints that must be taken up before steering inputs translate to actual wheel movement. The sensation is particularly noticeable when making small steering corrections on the highway, where the vehicle feels like it’s floating or wandering within its lane.

Excessive vibration transmitted through the steering wheel or felt throughout the cabin suggests severe ball joint wear. The loose joint allows the steering knuckle and wheel assembly to vibrate independently of the suspension, creating oscillations that transfer into the vehicle structure. This vibration typically worsens with speed and can become quite pronounced on highway travel.

Reduced steering precision and response means the vehicle doesn’t react as crisply to steering inputs as it once did. Corner entry feels mushy or imprecise, and the vehicle may seem unstable or nervous during lane changes. These symptoms indicate the ball joints can no longer maintain consistent wheel positioning during the dynamic forces of cornering and maneuvering.

Visible Symptoms

Visual inspection can reveal ball joint problems before handling symptoms become severe, making regular inspection during routine maintenance valuable for catching issues early.

Uneven tire wear patterns, specifically excessive wear on the inner or outer edges of front tires, often indicate alignment problems caused by worn ball joints. The excessive play allows camber and toe angles to shift beyond specification, causing the tire to contact the road at improper angles. This misalignment accelerates tread wear in predictable patterns—typically the inner edge wears faster, though outer edge wear is also possible depending on which direction the geometry has shifted.

Excessive or accelerated tire wear on the front tires specifically, even if the wear pattern appears relatively even across the tread, can signal ball joint problems affecting overall suspension geometry. When ball joints wear, they introduce instability that increases the tire scrubbing and slipping forces during normal driving, accelerating overall tire wear beyond normal rates.

Damaged dust boots represent a critical visual warning sign. Any tears, cracks, or grease leakage from the boot area indicates the joint’s protective barrier has been compromised. Once the boot fails, contamination enters rapidly and lubrication escapes, typically resulting in complete joint failure within months. Catching boot damage during visual inspection allows replacement before internal contamination destroys the joint.

Related suspension component damage may also indicate ball joint problems. Wear or damage to shock absorbers or other suspension parts can sometimes result from the increased motion and impact forces created by worn ball joints.

SAFETY WARNING: Severe ball joint wear can result in complete stud separation from the housing, causing the wheel to become partially disconnected from the vehicle. This represents an immediate and catastrophic loss of control that can result in serious accidents. Any symptoms of ball joint wear—audible noises, handling changes, or visible damage—require prompt professional inspection. Do not delay this safety-critical service.

Inspection and Diagnosis

Professional Inspection Methods

Accurate ball joint diagnosis requires proper equipment, technical knowledge, and understanding of the specific vehicle’s suspension design. Professional technicians follow systematic procedures to evaluate joint condition reliably.

The inspection process begins with lifting the vehicle on a hoist or using jack stands to provide access to the suspension components. The critical factor is positioning supports correctly based on ball joint type—load-bearing joints must be inspected with vehicle weight supported appropriately, while follower joints require different support positioning. Improper support can mask problems or create false indications of wear.

For load-bearing ball joints, the technician supports the vehicle’s weight at the lower control arm using a jack stand, allowing the joint to assume its normal loaded position. A dial indicator is then mounted to measure vertical movement at the steering knuckle while applying upward force to the wheel assembly. The measured axial play is compared to manufacturer specifications—typically between 0.020 and 0.060 inches maximum allowable play, though this varies significantly by application.

Follower ball joints require the Belleville washer or preload spring to be compressed or loaded during inspection to check for axial end play accurately. The support positioning differs from load-bearing joint inspection to properly load the preload mechanism. Again, dial indicator measurements provide precise data on the amount of play present.

Lateral play is evaluated by measuring horizontal movement at various points on the steering knuckle while applying side-to-side force. Excessive lateral play indicates worn bearing surfaces even if axial play remains within specification. Both measurements are necessary for complete evaluation.

Beyond measurements, visual inspection identifies boot condition, grease leakage, corrosion, and structural damage. The inspection often extends to related components since control arm bushing wear can create similar symptoms and may be discovered during ball joint evaluation.

DIY Pre-Inspection Checks

While professional diagnosis with precision instruments provides definitive results, informed vehicle owners can perform preliminary assessments to determine if professional inspection is warranted.

Begin with thorough visual inspection accessible from underneath the vehicle (using appropriate safety supports—never work under a vehicle supported only by a jack). Examine the dust boot carefully for any tears, cracks, or displacement. Look for grease residue around the boot area indicating seal failure. Check for rust or corrosion on visible components, and inspect the housing for cracks or obvious damage.

To perform a basic physical test, safely raise and support the vehicle following proper procedures. The exact support positioning depends on ball joint type—research your specific vehicle’s requirements before attempting this. Once properly supported, grasp the tire at the 12 o’clock and 6 o’clock positions and attempt to rock it vertically. Then grasp at 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock and rock horizontally. Excessive play, clicking sounds, or visible movement at the ball joint area suggests wear requiring professional evaluation.

During this physical test, have an assistant help by watching the ball joint directly while you rock the tire. They can often see movement that you can’t detect through feel alone. Listen carefully for clicking, popping, or grinding sounds as the joint articulates—these audible indicators often appear before play becomes obvious.

IMPORTANT: Ball joint replacement is not a typical DIY repair for most home mechanics. The process requires specialized tools including ball joint presses or hydraulic separators, pickle forks or ball joint separators, and substantial mechanical knowledge. Additionally, wheel alignment is mandatory after ball joint replacement, requiring professional equipment and expertise.

More critically, ball joints are safety-critical suspension components. Improper installation can result in joint failure and loss of vehicle control. Most intermediate DIYers should have ball joints inspected professionally and should strongly consider professional replacement due to the safety-critical nature, specialized tools required, and necessity for professional alignment afterward. This is not a repair to attempt without proper tools, knowledge, and alignment capabilities.

Maintenance and Service Life

Typical Lifespan

Ball joint longevity varies dramatically based on design type, vehicle application, driving conditions, and maintenance practices. Understanding realistic expectations helps with maintenance planning and budget preparation.

Sealed ball joints, which dominate modern original equipment applications, typically achieve service lives between 70,000 and 150,000 miles under normal driving conditions. The wide range reflects the numerous variables affecting wear rates. Light vehicles driven primarily on smooth highways in temperate climates often reach the upper end of this range or exceed it, while heavy trucks operated on rough roads in harsh winter climates with road salt exposure may require replacement toward the lower end.

Greaseable serviceable ball joints can substantially outlast sealed designs when properly maintained—achieving 100,000 to 200,000 miles or more isn’t uncommon with consistent lubrication service. However, this advantage depends entirely on the owner actually performing the maintenance. Neglected greaseable joints often fail sooner than well-designed sealed joints because dried-out lubricant creates destructive friction.

Load-bearing ball joints typically wear 1.5 to 2 times faster than follower joints under comparable conditions due to the additional stress from constantly supporting vehicle weight. This means in a double-wishbone suspension with load-bearing lower joints and follower upper joints, the lower joints often require replacement first, though best practice usually dictates replacing all four simultaneously for balanced performance.

Climate significantly affects service life. Vehicles operated in regions using road salt during winter experience accelerated corrosion of boots and housings, often reducing lifespan by 30-50% compared to similar vehicles in dry climates. The salt attacks rubber boots and metal housings, creating paths for contamination while the salt-laden water itself acts as an abrasive grinding compound once inside the joint.

Driving style and road conditions matter enormously. Aggressive driving with hard cornering creates higher lateral forces accelerating bearing wear. Frequent travel on rough, potholed roads subjects joints to more impacts and suspension movement cycles. Conversely, gentle driving on well-maintained roads extends joint life significantly.

Preventive Maintenance

Proactive maintenance can substantially extend ball joint service life and prevent premature failure, though the specific maintenance requirements depend on joint type.

For greaseable ball joints, consistent lubrication represents the single most important maintenance task. Service intervals typically range from every 2,000 to 5,000 miles depending on the specific joint design and operating conditions. Performance applications with low-friction bearings may require the shorter interval, while heavy-duty designs with robust seals can tolerate longer intervals. The greasing process serves dual purposes—providing fresh lubricant while using hydraulic pressure to purge old grease and any contaminants that may have infiltrated the joint.

Use only grease specifically formulated for ball joint and suspension applications. These greases incorporate additives for extreme pressure resistance, water resistance, and thermal stability that general-purpose greases lack. Apply grease until fresh grease appears at the boot seal, indicating the old grease has been displaced and the joint cavity is completely filled.

For sealed ball joints, preventive maintenance focuses on protection and early detection rather than servicing the joint itself. During every tire rotation or service, visually inspect all ball joint boots for tears, cracks, or damage. Catching boot failure immediately allows replacement before contamination destroys the internal components. Some technicians apply protective boot treatments or replace boots preventively in harsh environments.

Regular wheel alignment checks help detect ball joint wear early through changes in alignment angles or difficulty achieving specification during alignment service. An alignment that repeatedly loses adjustment or requires extreme compensation may indicate developing ball joint wear. Scheduling alignments annually or after significant impacts helps catch problems before handling symptoms appear.

When replacing any ball joints, replacing both sides simultaneously ensures balanced suspension performance and prevents premature failure of the remaining old joint due to altered suspension dynamics. Many technicians also recommend replacing upper and lower joints together in double-wishbone systems, even if only one shows wear, to avoid a second labor-intensive replacement shortly after.

Replacement Considerations

When ball joint replacement becomes necessary, several factors influence the quality and longevity of the repair.

The choice between OEM and aftermarket replacement parts involves trade-offs. Original equipment ball joints match factory specifications precisely and typically use sealed designs requiring no maintenance. Quality aftermarket options often offer greaseable designs allowing extended service life through maintenance, and some provide improved materials or bearing designs specifically addressing known weaknesses in original equipment. However, inferior aftermarket joints using substandard materials can fail prematurely—research and part selection matter significantly.

Installation method varies by vehicle design. Press-in ball joints require a hydraulic press or specialized ball joint press tool to remove the old joint and install the new one into the control arm. Bolt-in designs attach with bolts and are generally easier to install. Riveted original equipment joints require drilling out the rivets and using bolts to attach the replacement. Each method demands specific tools and techniques.

Wheel alignment after ball joint replacement is absolutely mandatory, not optional. The replacement process disturbs suspension geometry, and even small misalignment creates uneven tire wear and handling problems. Professional alignment ensures the suspension returns to manufacturer specifications. Attempting to skip this step to save money will cost more in accelerated tire wear and potential safety issues.

Professional service is strongly recommended for ball joint replacement due to the safety-critical nature of these components, specialized tools required, and mandatory alignment afterward. While experienced home mechanics with proper equipment can perform this work, most vehicle owners should rely on qualified professionals who have the correct tools, technical knowledge, and alignment equipment to perform the job correctly and safely.

Conclusion

Ball joints represent one of the most ingenious solutions in automotive suspension engineering—simple in concept yet sophisticated in execution. Their ball-and-socket design enables the complex three-dimensional movement modern vehicles require, allowing suspension travel and steering input to occur simultaneously while supporting enormous loads. Without these precision pivot points, the comfortable, controlled driving experience we take for granted would be impossible.

Understanding the distinction between load-bearing and follower ball joints helps explain why some joints wear faster than others and why replacement intervals vary. Load-bearing designs support vehicle weight in addition to handling dynamic forces, accelerating their wear progression. Follower joints, freed from constant weight-bearing duty, typically achieve longer service lives but still demand attention when symptoms appear.

Wear in ball joints is inevitable through normal use, but the progression from new to replacement follows a predictable pattern. Initial wear occurs silently as preload mechanisms compensate. Eventually, clearance exceeds compensation capability and symptoms emerge—first as occasional noises, then as handling changes, and finally as dangerous instability. Recognizing these warning signs early and responding promptly protects both safety and budget.

For greaseable ball joints, proper maintenance dramatically extends service life. The modest investment in regular lubrication service can double or triple longevity compared to neglected joints. For sealed designs, vigilant monitoring through periodic inspection catches problems before they progress to dangerous levels.

The safety-critical nature of ball joints cannot be overstated. These components literally hold your wheels to your vehicle. Failure doesn’t mean your car stops working properly—it means you lose control, potentially with catastrophic consequences. Any suspected ball joint wear demands immediate professional inspection, not deferral or “wait and see” approaches.

Remember: While understanding how ball joints work helps you maintain your vehicle intelligently and recognize when problems develop, diagnosis and replacement of these safety-critical components should be entrusted to qualified professionals. The consequences of ball joint failure—sudden loss of vehicle control—make this a repair that demands expertise, proper tools, and professional alignment equipment. Don’t gamble with safety on this critical suspension component.